Rosie Jackson digs into the foundations of an inventive and mysterious chapbook by Helen Ivory

Maps of the Abandoned City

Helen Ivory

SurVision Books, 2019

ISBN 978-1-912963-04-1

32 pp € 6.99

Maps of the Abandoned City

Helen Ivory

SurVision Books, 2019

ISBN 978-1-912963-04-1

32 pp € 6.99

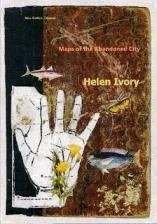

When I saw a new pamphlet by Helen Ivory offering itself for review, I snatched it up with all the eagerness of being promised sight of a waking dream, only to find it equally elusive as I tried to translate its wonder and exuberant surrealism into the rational language of a critique. The result is that the startlingly beautiful cover (one of Helen’s own collaged images) of Maps of the Abandoned City sat on my shelf and stared at me accusingly for months.

Then something came to my aid: a visit in June to the Dorothea Tanning exhibition at the Tate Modern. Tanning, a sublimely gifted artist, was one of the first women to fully embrace surrealism. She described its ‘limitless expanse of POSSIBILITY’, and produced stunning paintings and soft sculptures which mix the human and inanimate, the bizarre and the everyday, the exotic and erotic, in extraordinarily playful yet disturbing, sinister and thought-provoking ways. Tanning takes us into landscapes of ‘unknown but knowable states’; she wrote ‘I wanted to lead the eye into spaces that hid, revealed, transformed all at once and where there could be some never-before-seen image.’

Helen Ivory’s imagination is similarly inventive, daring, suggestive and uncategorisable, moving between poetry and art and, again like Tanning, with an edge of feminist subversion that is never laboured, but part of an irrepressible, fertile, prolific but ultimately politicised creativity.

Not that I can pretend to ‘understand’ Maps of the Abandoned City; the poems are not parables or allegories. Like dreams, they are not meant to be reduced from their images. As Wallace Stevens put it, ‘Poetry must resist the intelligence almost successfully,’ and these poems most certainly do.

What is the abandoned city? A post-apocalypse metropolis? A dream landscape? A (patriarchal) city at the end of its days, undone by human disaster and waiting to be re-made in less gendered terms?

In the first poem, a female cartographer steps ‘from a fold in the sky’, and in the poems that follow she guides us through streets she draws into being: Streets of the Candlemaker, Illusionist, Graveyard, Birds, Kings. Nothing is what it seems. My two favourite poems are ‘The Cartographer Takes a Day Off’ and ‘The Cartographer Unmakes’, perhaps because these are less trapped by the conceit of the abandoned city (shades of Norwich here, perhaps, with the castle?) and leave us with an image, however illusory, of freedom. Here is the whole text of the final poem, ‘The Cartographer Unmakes’:

It’s snow that gives her the idea,

bleaching parks of desire lines

and blotting out coffin paths.

With a white paintbrush

she makes a halo of the ring road

and cancels out the tower block and castle.

And when there is no one left

to remember the City,

when all has turned to fireside yarns and myth,

a traveller will open out

some spotless pages of the map

and imagine lady fortune shines on him.

There are wonderful evocations here. They erase urban history and architecture, things to do with death and enclosure, oppression, the predictable old desire lines. Snow can wipe things out, art can undo the old, transform what contains and constricts into what liberates, and underneath all this there’s more than a hint that the gendered oppressions have been the worst: it is the woman who does the wiping out, opens the possibility of making things new, though the final image gives no easy optimism that men will make a new life in any way different from the old – ‘imagine lady fortune shines on him’… the old male projections are still there, the happy ending far less realisable than the deliciously liberating image of snow, whiteness, erasure, which for me conjures something close to Tanning’s ‘limitless expanse of POSSIBILITY’.

All the poems allow for this kind of exacting reading, resisting the intelligence almost successfully. For me, their genius lies in the rare skill Ivory has to make her surrealism float into a world where politics – particularly sexual politics – are still pertinent, as if she’s found a way to keep asking questions about the politics of the unconscious even while she’s in the trance needed to write such mesmerising poetry. It’s the kind of deep feminism Laura Mulvey voiced and explored in her ground-breaking film The Riddles of the Sphinx in 1977 (when Helen Ivory was all of eight years old!), trying to find ways to give women’s subjectivity a voice. But where Mulvey’s generation gave the deep roots and theoretical understanding of psychoanalysis and feminism, Ivory, being the next generation, has it in her blood, and – thank God – can give us the pleasure and play of images, no less profound, but able to draw on imagination as much as intellect.

Thus we get flashes, as in ‘snapshots of the city’:

two forks

locked together

at the edge of a road.

the geography of landfill,

the surrendering to dust.

And in ‘The Photographic Albums of the Abandoned City’:

Light has leeched into the body

of the camera

so the bride wears a black dress,

a garland of shadows.

Perhaps the best way into Helen Ivory’s work, though, is ‘Wunderkammer with Black Coffee: Helen Ivory interviewed by William Bedford’, posted online in The High Window on May 16 2019. www.thehighwindowpress.com. This is a superb and fascinating dialogue between two poets and gives a rich context to Ivory’s work. She talks here about her collage method of making works of art, and how unexpected juxtapositions create new meaning:

‘I began making collages using the process as an exercise for students

on a starting to write poetry course. I was directing them to find surprise

in juxtaposition as a kick start for writing poems, but I quickly realised

that actually these WERE the poems, and whatever background you stuck

the words to, or images you added, became part of the meaning… When

making the collages or assemblages nothing is arbitrary, a logic is created…

sometimes dream logic rich in metaphor and symbolism… what I hope will

happen – is that meanings and connotations are/will be shifted in the

juxtaposition of tone, by the wit and mischievous imagination of placing text

from old educational books, fairytale books and women’s magazines into

the arena of a contemporary reading. They are far more than a simple ironic

take on an earlier age; they inform where we – and women in particular –

find ourselves now by digging deep. There is heartbreak in the innocence of

their dreams; beauty and strength in the weight and imbalance of societal

expectation. They are also songs to remind us of wonder: the habits of bees

and small crawling creatures; electricity and other sorcery.’

I cannot recommend this High Window interview too strongly: it is a brilliant and stimulating discussion of a poet’s process, poetics and politics. It touches on Maps of the Abandoned City and shows the usefulness of a relatively small project like this in between longer works – hot on its heels came Helen Ivory’s next full collection from Bloodaxe: The Anatomical Venus. It’s good to know there’s much more to come yet, all distinguished by Ivory’s hallmark of radical inventiveness and the exuberant yet purposeful dreamlike image.

Rosie Jackson is author of The Light Box (Cultured Llama 2016). Two Girls and a Beehive: Poems about Stanley Spencer and Hilda Carline (a collaboration with Graham Burchell) will come out from Two Rivers Press in April 2020. www.rosiejackson.org.uk

Jul 19 2019

London Grip Poetry Review – Helen Ivory

Rosie Jackson digs into the foundations of an inventive and mysterious chapbook by Helen Ivory

When I saw a new pamphlet by Helen Ivory offering itself for review, I snatched it up with all the eagerness of being promised sight of a waking dream, only to find it equally elusive as I tried to translate its wonder and exuberant surrealism into the rational language of a critique. The result is that the startlingly beautiful cover (one of Helen’s own collaged images) of Maps of the Abandoned City sat on my shelf and stared at me accusingly for months.

Then something came to my aid: a visit in June to the Dorothea Tanning exhibition at the Tate Modern. Tanning, a sublimely gifted artist, was one of the first women to fully embrace surrealism. She described its ‘limitless expanse of POSSIBILITY’, and produced stunning paintings and soft sculptures which mix the human and inanimate, the bizarre and the everyday, the exotic and erotic, in extraordinarily playful yet disturbing, sinister and thought-provoking ways. Tanning takes us into landscapes of ‘unknown but knowable states’; she wrote ‘I wanted to lead the eye into spaces that hid, revealed, transformed all at once and where there could be some never-before-seen image.’

Helen Ivory’s imagination is similarly inventive, daring, suggestive and uncategorisable, moving between poetry and art and, again like Tanning, with an edge of feminist subversion that is never laboured, but part of an irrepressible, fertile, prolific but ultimately politicised creativity.

Not that I can pretend to ‘understand’ Maps of the Abandoned City; the poems are not parables or allegories. Like dreams, they are not meant to be reduced from their images. As Wallace Stevens put it, ‘Poetry must resist the intelligence almost successfully,’ and these poems most certainly do.

What is the abandoned city? A post-apocalypse metropolis? A dream landscape? A (patriarchal) city at the end of its days, undone by human disaster and waiting to be re-made in less gendered terms?

In the first poem, a female cartographer steps ‘from a fold in the sky’, and in the poems that follow she guides us through streets she draws into being: Streets of the Candlemaker, Illusionist, Graveyard, Birds, Kings. Nothing is what it seems. My two favourite poems are ‘The Cartographer Takes a Day Off’ and ‘The Cartographer Unmakes’, perhaps because these are less trapped by the conceit of the abandoned city (shades of Norwich here, perhaps, with the castle?) and leave us with an image, however illusory, of freedom. Here is the whole text of the final poem, ‘The Cartographer Unmakes’:

There are wonderful evocations here. They erase urban history and architecture, things to do with death and enclosure, oppression, the predictable old desire lines. Snow can wipe things out, art can undo the old, transform what contains and constricts into what liberates, and underneath all this there’s more than a hint that the gendered oppressions have been the worst: it is the woman who does the wiping out, opens the possibility of making things new, though the final image gives no easy optimism that men will make a new life in any way different from the old – ‘imagine lady fortune shines on him’… the old male projections are still there, the happy ending far less realisable than the deliciously liberating image of snow, whiteness, erasure, which for me conjures something close to Tanning’s ‘limitless expanse of POSSIBILITY’.

All the poems allow for this kind of exacting reading, resisting the intelligence almost successfully. For me, their genius lies in the rare skill Ivory has to make her surrealism float into a world where politics – particularly sexual politics – are still pertinent, as if she’s found a way to keep asking questions about the politics of the unconscious even while she’s in the trance needed to write such mesmerising poetry. It’s the kind of deep feminism Laura Mulvey voiced and explored in her ground-breaking film The Riddles of the Sphinx in 1977 (when Helen Ivory was all of eight years old!), trying to find ways to give women’s subjectivity a voice. But where Mulvey’s generation gave the deep roots and theoretical understanding of psychoanalysis and feminism, Ivory, being the next generation, has it in her blood, and – thank God – can give us the pleasure and play of images, no less profound, but able to draw on imagination as much as intellect.

Thus we get flashes, as in ‘snapshots of the city’:

And in ‘The Photographic Albums of the Abandoned City’:

Perhaps the best way into Helen Ivory’s work, though, is ‘Wunderkammer with Black Coffee: Helen Ivory interviewed by William Bedford’, posted online in The High Window on May 16 2019. www.thehighwindowpress.com. This is a superb and fascinating dialogue between two poets and gives a rich context to Ivory’s work. She talks here about her collage method of making works of art, and how unexpected juxtapositions create new meaning:

I cannot recommend this High Window interview too strongly: it is a brilliant and stimulating discussion of a poet’s process, poetics and politics. It touches on Maps of the Abandoned City and shows the usefulness of a relatively small project like this in between longer works – hot on its heels came Helen Ivory’s next full collection from Bloodaxe: The Anatomical Venus. It’s good to know there’s much more to come yet, all distinguished by Ivory’s hallmark of radical inventiveness and the exuberant yet purposeful dreamlike image.

Rosie Jackson is author of The Light Box (Cultured Llama 2016). Two Girls and a Beehive: Poems about Stanley Spencer and Hilda Carline (a collaboration with Graham Burchell) will come out from Two Rivers Press in April 2020. www.rosiejackson.org.uk

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2019 1 • Tags: books, poetry, Rosie Jackson