Stuart Henson reflects on the serendipity that led to the creation of a high-quality artist’s book from Redfox Press which combines photographic images with poems by John Greening

Achill Island Tagebuch

John Greening

Redfox Press, 2019.

(No ISBN)

44pp £30.00

Achill Island Tagebuch

John Greening

Redfox Press, 2019.

(No ISBN)

44pp £30.00

Sometimes things fall perfectly into place. Not always, but sometimes. And this happened for my good friend John Greening last summer when he took on a fortnight’s residency at the Heinrich Böll Cottage on Achill Island in the west of County Mayo. For John, a professed Germanophile and Yeats enthusiast, the residency was something of a gift. What’s not to like, indeed, about sea, solitude, sunlight and Slievemore in the distance? The only hazard might be that having arrived in such a time-hallowed spot a certain obligation, for a writer at least, hangs in the air.

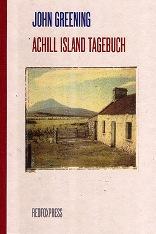

Never one to shirk a challenge, he set about recording the events from day to day of his stay in the sequence of sonnets that make up this delightful little book—and to set the seal upon it, whom should he find not much more than a mile away from the cottage but the perfect publisher for such a work. Redfox is the imprint of two artists, Francis van Maele and Antic-ham (known collectively as Franticham) who make fine press editions of painters, photographers and writers from Europe and the US, selling them at book-fairs throughout the world, so as you would expect, the production values of this volume are extremely high. Measuring 15 x 20 cm the Achill Island Tagebuch, so named in honour of Böll’s own Irish Journal, is hand sewn, bound in matt boards with a cloth spine and laser-printed in a numbered edition of 150. The cover features an emulsion-transfer image from a polaroid of an Achill cottage with the mountain in the background, and the text is artfully interspersed with five more of Franticham’s atmospheric photographs which set the context and interact resonantly with the poems.

The sonnet has been a serviceable form ever since it was imported from the continent. Its fourteen lines give you time to draw out an idea and wrestle it to a conclusion. The rhymes allow for a degree of detachment and a leavening of wit. In these respects it’s well-suited to John Greening’s project which is not unlike those ‘encounter groups’ popular in the seventies in which the participants analyse the behaviour of the group as they go along—though this is determinedly a group of one.

That’s not to say that other characters don’t appear. The ghost of Böll taps him on the back in the first poem and Greening returns the compliment by rhyming him twice – with ‘school’ and ‘scroll’ – before clinching the Shakespearian scheme with ‘sonnet’ and ‘chanced upon it’. In others we meet a German family who happen to be touring; another artist, Conor Gallagher; a hill walker searching for a path, and somewhat enigmatically, ‘Two girls who are ‘researching jellyfish’’, characterised in the title as “Medusae,” who have left a note at his gate.

…They say they wish

to discover more (‘let’s have a drink’) about –

well, who knows what precisely they are after.

One’s French, one’s Dutch. I’m going to ignore them,

though they’re ‘very curious’ and (cue your laughter)

are hoping to ‘share thoughts.’

The poet, admirably, retains focus on his self-imposed task (‘My thoughts would bore them’) but you can’t help wondering what mythological and ecological delights he, or they, may have missed out on.

Greening, indeed, seems more at home with the books of those who have come before him to the cottage, like the Irish writer Moya Cannon, or with the spirits of Yeats, John F. Deane, Seamus Heaney and Dennis O’Driscoll who fly in and out of the sonnets like wild swans. The presiding genius, naturally, is Böll in whose ‘privater Ort’

…artists may ‘an ihren Werken arbeiten’,

or hang above a cold, sheer gulf of thought

releasing vowels folded to a pattern

with images: a peace agreement signed

on both sides of the gate…

Our hermit, however, is not without a sense of humour. If he must be torn at all it is for his penchant for ingenious word-play. In “Accompaniment”, for example we find him walking with the sea on his left hand, ‘shimmering there, playing soul-/ful accompaniment to your right hand / the piece (as long as it’s in C)…’ Good poets, according to Auden have a weakness for bad puns, but in the sonnet “Mars” in which Greening tells us that ‘news comes dropping slow / on Achill’ he takes the art to a whole new level concluding

…This is the power

of looking out from headlines to the sea,

and listening for the news that’s in us, free.

My own preference is for the poems where landscape fuses with mythology and circumstance, as in “The Pale Helmet” which begins

Thinking about O’Driscoll, I looked down

to where my helmet lay, after my long

heroic quest into the drifts, the dunes,

the tall and tufted reeds. It was the wrong

colour. There seems to be an error. Not mine.

Yet mine is clearly nowhere in the house.

This changeling has been left. During my spin,

I must have been diverted by some host

of the air of Achill.

The half-rhymes run smooth, and the creative ambiguity of the ‘Not mine’ (both error and helmet) works happily. There’s a self-deprecating irony in the play of the helmet and hero imagery that’s attractive too. The polaroid of a bicycle against a cottage wall, sharing the spread with the poem, is a pleasing example also of the understated effectiveness of Franticham’s contributions.

Not everyone, I realise, will be able to afford the £30 or 35 Euros that place the Achill Island Tagebuch firmly in the artist’s-book collector’s market, but for those who can, it’s a travelogue that’s well worth the sharing. If you can’t, and still fancy a look at the Sonnetmeister at work, there’s always Greening’s New Walk pamphlet Europa’s Flight scheduled for later in the year.

Mar 15 2019

London Grip Poetry Review – John Greening

Stuart Henson reflects on the serendipity that led to the creation of a high-quality artist’s book from Redfox Press which combines photographic images with poems by John Greening

Sometimes things fall perfectly into place. Not always, but sometimes. And this happened for my good friend John Greening last summer when he took on a fortnight’s residency at the Heinrich Böll Cottage on Achill Island in the west of County Mayo. For John, a professed Germanophile and Yeats enthusiast, the residency was something of a gift. What’s not to like, indeed, about sea, solitude, sunlight and Slievemore in the distance? The only hazard might be that having arrived in such a time-hallowed spot a certain obligation, for a writer at least, hangs in the air.

Never one to shirk a challenge, he set about recording the events from day to day of his stay in the sequence of sonnets that make up this delightful little book—and to set the seal upon it, whom should he find not much more than a mile away from the cottage but the perfect publisher for such a work. Redfox is the imprint of two artists, Francis van Maele and Antic-ham (known collectively as Franticham) who make fine press editions of painters, photographers and writers from Europe and the US, selling them at book-fairs throughout the world, so as you would expect, the production values of this volume are extremely high. Measuring 15 x 20 cm the Achill Island Tagebuch, so named in honour of Böll’s own Irish Journal, is hand sewn, bound in matt boards with a cloth spine and laser-printed in a numbered edition of 150. The cover features an emulsion-transfer image from a polaroid of an Achill cottage with the mountain in the background, and the text is artfully interspersed with five more of Franticham’s atmospheric photographs which set the context and interact resonantly with the poems.

The sonnet has been a serviceable form ever since it was imported from the continent. Its fourteen lines give you time to draw out an idea and wrestle it to a conclusion. The rhymes allow for a degree of detachment and a leavening of wit. In these respects it’s well-suited to John Greening’s project which is not unlike those ‘encounter groups’ popular in the seventies in which the participants analyse the behaviour of the group as they go along—though this is determinedly a group of one.

That’s not to say that other characters don’t appear. The ghost of Böll taps him on the back in the first poem and Greening returns the compliment by rhyming him twice – with ‘school’ and ‘scroll’ – before clinching the Shakespearian scheme with ‘sonnet’ and ‘chanced upon it’. In others we meet a German family who happen to be touring; another artist, Conor Gallagher; a hill walker searching for a path, and somewhat enigmatically, ‘Two girls who are ‘researching jellyfish’’, characterised in the title as “Medusae,” who have left a note at his gate.

The poet, admirably, retains focus on his self-imposed task (‘My thoughts would bore them’) but you can’t help wondering what mythological and ecological delights he, or they, may have missed out on.

Greening, indeed, seems more at home with the books of those who have come before him to the cottage, like the Irish writer Moya Cannon, or with the spirits of Yeats, John F. Deane, Seamus Heaney and Dennis O’Driscoll who fly in and out of the sonnets like wild swans. The presiding genius, naturally, is Böll in whose ‘privater Ort’

Our hermit, however, is not without a sense of humour. If he must be torn at all it is for his penchant for ingenious word-play. In “Accompaniment”, for example we find him walking with the sea on his left hand, ‘shimmering there, playing soul-/ful accompaniment to your right hand / the piece (as long as it’s in C)…’ Good poets, according to Auden have a weakness for bad puns, but in the sonnet “Mars” in which Greening tells us that ‘news comes dropping slow / on Achill’ he takes the art to a whole new level concluding

My own preference is for the poems where landscape fuses with mythology and circumstance, as in “The Pale Helmet” which begins

The half-rhymes run smooth, and the creative ambiguity of the ‘Not mine’ (both error and helmet) works happily. There’s a self-deprecating irony in the play of the helmet and hero imagery that’s attractive too. The polaroid of a bicycle against a cottage wall, sharing the spread with the poem, is a pleasing example also of the understated effectiveness of Franticham’s contributions.

Not everyone, I realise, will be able to afford the £30 or 35 Euros that place the Achill Island Tagebuch firmly in the artist’s-book collector’s market, but for those who can, it’s a travelogue that’s well worth the sharing. If you can’t, and still fancy a look at the Sonnetmeister at work, there’s always Greening’s New Walk pamphlet Europa’s Flight scheduled for later in the year.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • art, books, photography, poetry reviews, year 2019 0 • Tags: art, books, photography, poetry, Stuart Henson