Paintings by Howard Fritz

at the Torriano Meeting House, 99 Torriano Avenue, London, NW5 2RX

from January 12th 2019

Work can be seen before & during all Torriano events –

see https://torrianomeetinghouse.wordpress.com/

The pleasure of writing about the well-attended opening of a new show of Howard Fritz paintings at The Torriano Meeting House is overshadowed by the awareness that this is a posthumous exhibition. Sadly, this very distinctive and original artist died in spring 2018 after a long illness, during which he was unable to paint. He did however leave a very considerable back catalogue and the dozen or so examples included here provide a welcome reminder of his gifts. As a friend and sometime collaborator in pairing poems with his images, I am glad of one more chance to comment on his work – and perhaps to introduce it to a fresh audience (see http://hwfritz.blogspot.com/ for numerous further examples).

The exhibition has been curated by Emily Johns , making selections from the archive held by Leah Fritz, and the paintings on display today are in some ways rather different from those featured in Howard’s previous Torriano exhibition exactly three years ago (described at https://londongrip.co.uk/2016/01/paintings-by-howard-fritz-at-the-torriano/). There are of course examples of his characteristic surreal juxtaposing of well-drawn but unrelated objects. What, for instance, are we to make of the imperious Nanny who may be trying to turn back the ocean liner that seems bent upon colliding with the dockside? And where is the child that should be in the pushchair? How has an astronaut’s helmet arrived at the top of an escalator leading to the Underground?

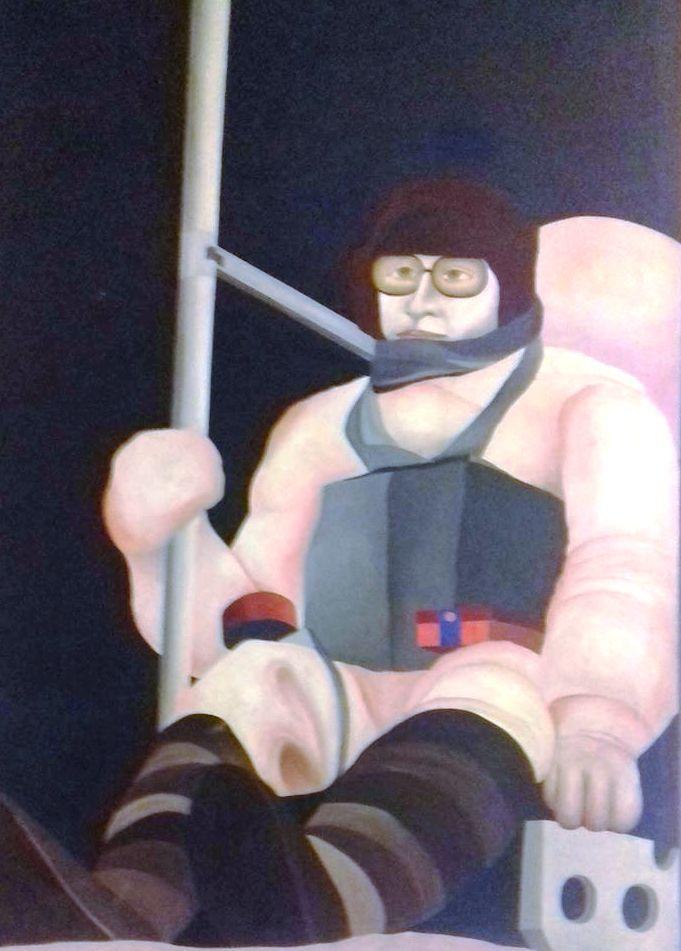

But, in contrast with the previous exhibition, we have here some earlier works in which Howard concentrated on a single subject. An example is the grotesque figure with goggles and balaclava hat who seems to be ascending in a chair-lift. But then, on the opposite wall, we see, perhaps, the tentative beginnings of the development of Howard’s later collage approach as he brings distinct elements together in the image of the seemingly levitating man operating a hoist to raise an empty bucket. Both these pictures involve much darker tones than the ones the artist adopted in his later, wonderfully luminescent canvases. There is one further picture, not illustrated here, which seems also to belong to the earlier, less complex, period and this too features a dark background in the middle of which theatre curtains are opening to reveal – startlingly – an oncoming aircraft.

Each of these early pieces involves a machine of some sort; and Howard never seemed to lose his interest in the look of devices and contraptions of all kinds. (He was perhaps less concerned with how they actually worked.) An old fashioned washing machine behind a twisted tree was probably copied from 1930s advertising material – such things were a frequent source of inspiration. But he also drew on books and magazines about film since he was an enthusiastic movie-buff, being especially fond of films from the 1940s and 50s. Hence the soldiers in the left foreground could well have been captured from a still from a First World War movie.

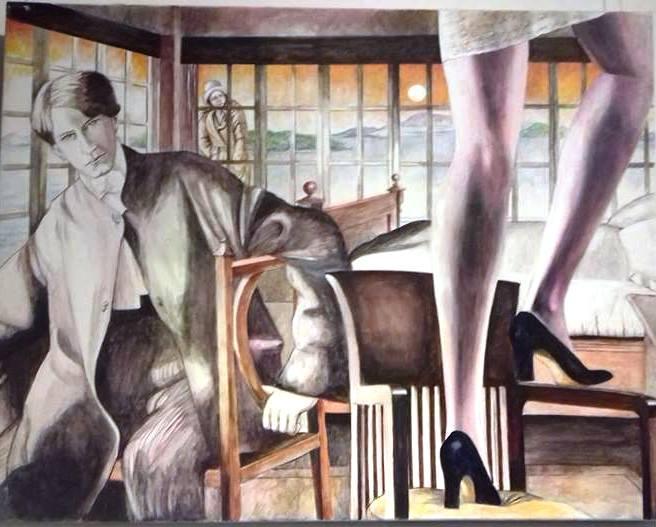

However we should not think of Howard as being merely a copyist of existing images. Consider the enigmatic tableau involving a troubled-looking Victorian gentleman who is clearly distracted from paying attention to the woman who stands plaintively outside the window behind him. Howard may have started with a simple reproduction of the elegant chair in the foreground – but must then have decided it would be significantly enhanced by a pair of long legs in a short skirt. We cannot of course know the order in which the elements of the composition were introduced; but it is satisfying to conjecture that the legs might have been introduced to undercut the seriousness in the Heathcliff-Cathy scenario (?) hinted at in the left half of the painting.

There is, inevitably, a good deal of speculation in the preceding paragraphs. Howard seldom if ever volunteered an “interpretation” of his pictures; but he was always politely receptive of any theories that might be advanced by a viewer. Many artists, past and present, have published rather directive – not to say incomprehensible – manifestos as a way of promoting/explaining themselves and their work. Howard seems to have preferred to devote his time to producing paintings rather than analysing them; and in doing so he has left his audience free either to conduct its own philosophical ponderings or simply to enjoy some genuinely delightful pictures which keep offering fresh surprises.

Michael Bartholomew-Biggs

Jan 13 2019

Howard Fritz – A Retrospective

Paintings by Howard Fritz

at the Torriano Meeting House, 99 Torriano Avenue, London, NW5 2RX

from January 12th 2019

Work can be seen before & during all Torriano events –

see https://torrianomeetinghouse.wordpress.com/

The pleasure of writing about the well-attended opening of a new show of Howard Fritz paintings at The Torriano Meeting House is overshadowed by the awareness that this is a posthumous exhibition. Sadly, this very distinctive and original artist died in spring 2018 after a long illness, during which he was unable to paint. He did however leave a very considerable back catalogue and the dozen or so examples included here provide a welcome reminder of his gifts. As a friend and sometime collaborator in pairing poems with his images, I am glad of one more chance to comment on his work – and perhaps to introduce it to a fresh audience (see http://hwfritz.blogspot.com/ for numerous further examples).

The exhibition has been curated by Emily Johns , making selections from the archive held by Leah Fritz, and the paintings on display today are in some ways rather different from those featured in Howard’s previous Torriano exhibition exactly three years ago (described at https://londongrip.co.uk/2016/01/paintings-by-howard-fritz-at-the-torriano/). There are of course examples of his characteristic surreal juxtaposing of well-drawn but unrelated objects. What, for instance, are we to make of the imperious Nanny who may be trying to turn back the ocean liner that seems bent upon colliding with the dockside? And where is the child that should be in the pushchair? How has an astronaut’s helmet arrived at the top of an escalator leading to the Underground?

But, in contrast with the previous exhibition, we have here some earlier works in which Howard concentrated on a single subject. An example is the grotesque figure with goggles and balaclava hat who seems to be ascending in a chair-lift. But then, on the opposite wall, we see, perhaps, the tentative beginnings of the development of Howard’s later collage approach as he brings distinct elements together in the image of the seemingly levitating man operating a hoist to raise an empty bucket. Both these pictures involve much darker tones than the ones the artist adopted in his later, wonderfully luminescent canvases. There is one further picture, not illustrated here, which seems also to belong to the earlier, less complex, period and this too features a dark background in the middle of which theatre curtains are opening to reveal – startlingly – an oncoming aircraft.

Each of these early pieces involves a machine of some sort; and Howard never seemed to lose his interest in the look of devices and contraptions of all kinds. (He was perhaps less concerned with how they actually worked.) An old fashioned washing machine behind a twisted tree was probably copied from 1930s advertising material – such things were a frequent source of inspiration. But he also drew on books and magazines about film since he was an enthusiastic movie-buff, being especially fond of films from the 1940s and 50s. Hence the soldiers in the left foreground could well have been captured from a still from a First World War movie.

However we should not think of Howard as being merely a copyist of existing images. Consider the enigmatic tableau involving a troubled-looking Victorian gentleman who is clearly distracted from paying attention to the woman who stands plaintively outside the window behind him. Howard may have started with a simple reproduction of the elegant chair in the foreground – but must then have decided it would be significantly enhanced by a pair of long legs in a short skirt. We cannot of course know the order in which the elements of the composition were introduced; but it is satisfying to conjecture that the legs might have been introduced to undercut the seriousness in the Heathcliff-Cathy scenario (?) hinted at in the left half of the painting.

There is, inevitably, a good deal of speculation in the preceding paragraphs. Howard seldom if ever volunteered an “interpretation” of his pictures; but he was always politely receptive of any theories that might be advanced by a viewer. Many artists, past and present, have published rather directive – not to say incomprehensible – manifestos as a way of promoting/explaining themselves and their work. Howard seems to have preferred to devote his time to producing paintings rather than analysing them; and in doing so he has left his audience free either to conduct its own philosophical ponderings or simply to enjoy some genuinely delightful pictures which keep offering fresh surprises.

Michael Bartholomew-Biggs

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • art, exhibitions, year 2019 0 • Tags: art, exhibitions, Michael Bartholomew-Biggs