Jenny Vuglar visits the strange worlds created by Paula Rego currently on show at the Jerwood Gallery, Hastings

Paula Rego: The Boy Who Loved the Sea and Other Stories.

The Jerwood Gallery, Hastings.

21 October – 7 January 2018.

The Jerwood Gallery in Hastings is five years old and the latest exhibition is a celebration – Paula Rego’s The Boy Who Loved the Sea and Other Stories is a celebration of a wonderful, macabre, horrifying and glorious artist – and a celebration of the Gallery’s position, on the beach rump up against boats and shingle. Hastings is a seaside town whose out of season depression is slowly being lifted by arts-led regeneration. The Jerwood is a key part of this regeneration with its black nod to the tarred netting sheds and the wide glass windows that let in sea light. Even in November the café balcony is open to the swirl of gulls and fishing boats crawling back, hauled up the beach on winches.

The permanent collection specialises in mid 20th Century British art and the exhibitions have often complemented this from the opening exhibition of Gillian Ayre’s 1950’s canvases to Prunella Clough’s Lowestoft fishermen.

This exhibition takes its title from a Traditional Portuguese folk tale. Rego was born in Portugal and grew up in the difficult atmosphere of Salazar’s dictatorship. She came to London to finishing school and stayed for the Slade School of Art. She has spent most of her life moving back and forth between Portugal and London belonging to neither, belonging in the end ‘in the studio’. The dissonance of living between cultures is often a productive one and Rego exploits this outsider view showing us the darkness behind some of our most loved tales – I can only presume her Portuguese viewers feel the same. She is a story teller but as she has said ‘you might start with one story and finish with another’. The earliest works in this exhibition are selections from her 1989 Nursery Rhymes series. These are the stories we tell our children but these illustrations owe more to Goya’s Disasters of War etchings than bedtime comfort. She unsettles, not just with subject matter but with disrupted perspective, shadows that fall in the wrong place or reveal disturbing alter egos, heads too big for bodies, colours that seep and drip. In Three Blind Mice, as though the grotesque oversized mice were not enough, we see a tumbrel waiting in the street outside. Who goes to the guillotine next ?

The Peter Pan series has muscular mermaids who watch as Tiger Lily is tied to the rock or hold Wendy under. The same mermaids sweep around the gallery- grim faced, thin grey hair falling in streaks. The lost boys flying to Netherland are attacked by rooks. Even the classic Jane Eyre is made over, a series of lithographs exposing the misogyny; the mad wife in the attic sullen and unmoving.

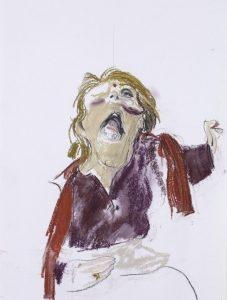

As her contemporaries moved from figuration to abstraction, Rego moved from abstraction to figuration, finding her heritage in Surrealism, in particular the emphasis on the subconscious. Rego prioritises the act of drawing, the pressure of the hand on paper, the physical contact that connects the artist and the medium. She finds what she wants by doing, letting the picture take her, show her. In an interview in 2008 she said “you have to trust the picture …and you discover in the end what it is, who you are. What you really feel sometimes isn’t very nice.” But, nice or not, that is where you go. Nothing has been off limits to Rego: lust, revenge, murder – and famously abortion. The Abortion series isn’t represented here but instead she has allowed a private series to be shown, called The Depression Series. Rego drew her long time friend and model, Lila Nunes, over a period of several months, as she lived her way through the depression that threatened to overcome her. This is not the traditional artist-model relationship. Nunes says “She is using me as her.” What we see here is something we almost never see – a woman stepping outside herself, becoming the thing she most dreads, holding it up, stepping out alive.

Personal too are the latest drawings, self portraits following a fall, her only self portraits. Although she denies that they reflect her frustration at aging (she is now 82) she also once famously said that she couldn’t understand why people found her prints macabre. Apparently she unpicked the stitches on her forehead because she hadn’t finished the drawings. There is a joy in honesty here. Thank God for the grotesque, for the bruises and scrapes, the flat on the face, bungled eyes, mess of a face – thank God for the reality of falling and for the pain of being human. This is a woman who never trusted beauty. This is the glory of Rego – that she allows into the gallery those images of women that have been exiled: those angry, vengeful, old, ugly, ill.

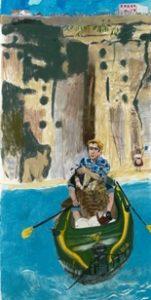

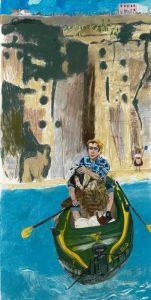

The large pastels that make up the bulk of the exhibition are mainly newish work based on Portuguese stories – some fantasies and some real. Of course the real are just as strange as the fantasies. The Last King of Portugal series made in 2014 tell the story of the deposed King Manuel who died in exile in Fulwell, Middlesex. His father and brother were assassinated and Rego shows him rowing out to sea, cradling his mother between his legs, travelling into exile. His death, an unexplained mystery of course, is accompanied by a maid who watches, twisting a cloth between her hands as he chokes.

The large pastels that make up the bulk of the exhibition are mainly newish work based on Portuguese stories – some fantasies and some real. Of course the real are just as strange as the fantasies. The Last King of Portugal series made in 2014 tell the story of the deposed King Manuel who died in exile in Fulwell, Middlesex. His father and brother were assassinated and Rego shows him rowing out to sea, cradling his mother between his legs, travelling into exile. His death, an unexplained mystery of course, is accompanied by a maid who watches, twisting a cloth between her hands as he chokes.

*

Rego’s work is full of narrative but they are not illustrations, they have their own life. They go beyond the story someone has told and move into dreams and nightmares. Rego doesn’t try to shock, she doesn’t try to do anything – she just allows the un-told stories to bustle up against the told. The story that makes up the title of the exhibition , a boy who longs to find the sea, ends, like the exhibition, at the sea shore, the boy as blue as the sky, as blue as the sea – blue because he is dead.

Nov 6 2017

Jenny Vuglar visits the strange worlds created by Paula Rego currently on show at the Jerwood Gallery, Hastings

Paula Rego: The Boy Who Loved the Sea and Other Stories.

The Jerwood Gallery, Hastings.

21 October – 7 January 2018.

The Jerwood Gallery in Hastings is five years old and the latest exhibition is a celebration – Paula Rego’s The Boy Who Loved the Sea and Other Stories is a celebration of a wonderful, macabre, horrifying and glorious artist – and a celebration of the Gallery’s position, on the beach rump up against boats and shingle. Hastings is a seaside town whose out of season depression is slowly being lifted by arts-led regeneration. The Jerwood is a key part of this regeneration with its black nod to the tarred netting sheds and the wide glass windows that let in sea light. Even in November the café balcony is open to the swirl of gulls and fishing boats crawling back, hauled up the beach on winches.

The permanent collection specialises in mid 20th Century British art and the exhibitions have often complemented this from the opening exhibition of Gillian Ayre’s 1950’s canvases to Prunella Clough’s Lowestoft fishermen.

This exhibition takes its title from a Traditional Portuguese folk tale. Rego was born in Portugal and grew up in the difficult atmosphere of Salazar’s dictatorship. She came to London to finishing school and stayed for the Slade School of Art. She has spent most of her life moving back and forth between Portugal and London belonging to neither, belonging in the end ‘in the studio’. The dissonance of living between cultures is often a productive one and Rego exploits this outsider view showing us the darkness behind some of our most loved tales – I can only presume her Portuguese viewers feel the same. She is a story teller but as she has said ‘you might start with one story and finish with another’. The earliest works in this exhibition are selections from her 1989 Nursery Rhymes series. These are the stories we tell our children but these illustrations owe more to Goya’s Disasters of War etchings than bedtime comfort. She unsettles, not just with subject matter but with disrupted perspective, shadows that fall in the wrong place or reveal disturbing alter egos, heads too big for bodies, colours that seep and drip. In Three Blind Mice, as though the grotesque oversized mice were not enough, we see a tumbrel waiting in the street outside. Who goes to the guillotine next ?

The Peter Pan series has muscular mermaids who watch as Tiger Lily is tied to the rock or hold Wendy under. The same mermaids sweep around the gallery- grim faced, thin grey hair falling in streaks. The lost boys flying to Netherland are attacked by rooks. Even the classic Jane Eyre is made over, a series of lithographs exposing the misogyny; the mad wife in the attic sullen and unmoving.

As her contemporaries moved from figuration to abstraction, Rego moved from abstraction to figuration, finding her heritage in Surrealism, in particular the emphasis on the subconscious. Rego prioritises the act of drawing, the pressure of the hand on paper, the physical contact that connects the artist and the medium. She finds what she wants by doing, letting the picture take her, show her. In an interview in 2008 she said “you have to trust the picture …and you discover in the end what it is, who you are. What you really feel sometimes isn’t very nice.” But, nice or not, that is where you go. Nothing has been off limits to Rego: lust, revenge, murder – and famously abortion. The Abortion series isn’t represented here but instead she has allowed a private series to be shown, called The Depression Series. Rego drew her long time friend and model, Lila Nunes, over a period of several months, as she lived her way through the depression that threatened to overcome her. This is not the traditional artist-model relationship. Nunes says “She is using me as her.” What we see here is something we almost never see – a woman stepping outside herself, becoming the thing she most dreads, holding it up, stepping out alive.

Personal too are the latest drawings, self portraits following a fall, her only self portraits. Although she denies that they reflect her frustration at aging (she is now 82) she also once famously said that she couldn’t understand why people found her prints macabre. Apparently she unpicked the stitches on her forehead because she hadn’t finished the drawings. There is a joy in honesty here. Thank God for the grotesque, for the bruises and scrapes, the flat on the face, bungled eyes, mess of a face – thank God for the reality of falling and for the pain of being human. This is a woman who never trusted beauty. This is the glory of Rego – that she allows into the gallery those images of women that have been exiled: those angry, vengeful, old, ugly, ill.

*

Rego’s work is full of narrative but they are not illustrations, they have their own life. They go beyond the story someone has told and move into dreams and nightmares. Rego doesn’t try to shock, she doesn’t try to do anything – she just allows the un-told stories to bustle up against the told. The story that makes up the title of the exhibition , a boy who longs to find the sea, ends, like the exhibition, at the sea shore, the boy as blue as the sky, as blue as the sea – blue because he is dead.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • art, exhibitions, year 2017 0 • Tags: art, exhibitions, Jenny Vuglar