Unseen Photography from the 19th Century.

Published by Hannibal Books to accompany the eponymous exhibition at FOMU – Fotomuseum, Antwerp until March 1.

Photography – or painting with light, from the Greek roots of the word – is slightly younger than the country of Belgium.

It began in 1839 when Frenchman Louis Daguerre gave the world the daguerreotype process that could create a detailed single image. Around the same time in Britain, William Henry Fox Talbot created a negative image that could be used to make multiple positive prints.

Meanwhile, Belgium, which declared independence in 1830, became a forerunner in photographic identification and is home to the oldest preserved mugshots, dating from 1843.

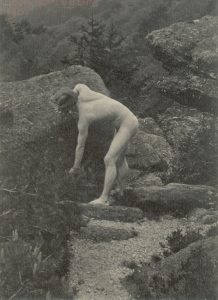

As well as using photography to catch criminals, Belgium led the way in putting the technique to arguably criminal uses, including pornography and the wider abuse of power, which sadly finds an echo in today’s AI image manipulation.

Notoriously, photography was one of the means used to reinforce King Leopold II ‘s personal control of the Congo Free State, which he claimed as his private property from 1885 until 1908. Then, under intense international pressure, he handed control to the country of Belgium, and it became known as the Belgian Congo.

Working from the premise that museums, like the rest of the traditional establishment, have typically been highly selective in what they present to the world, the Fotomuseum in Antwerp, known as the FOMU, takes a soul-searching look into past crimes of omission and commission – or the underexposed versus the exposed.

The accompanying book, at once erudite and appealing, combines haunting reproductions of early photographs with elegant academic essays.

Colonialism is the central theme. It carries a wider significance of the more general exertion of the powerful over the oppressed, of men over women and children and of industrial magnates over their labour forces.

At the top of the power structure, Leopold II presided over Belgium’s 1897 contribution to the trend of world fairs, which he used as the means to publicise the supposedly civilising mission of his private colony and its economic opportunities.

When Belgium’s international exhibition was held in Brussels, a colonial section was built in Tervuren on the outskirts of the capital. A “human zoo” was created there in the form of a copy of an African village, where for the duration of the exhibition 60 Congolese people lived – and seven of them died.

From our 21st-century perspective, surviving photographs of the captive Congolese show people tragically displaced in an alien land, forced to wear alien clothes.

In the late 19th-century, however, the exhibition was hailed as a great success and the neoclassical building then named the Palace of the Colonies became a permanent museum.

It was closed in 2013 for a five-year renovation that was structurally necessary but also allowed for a makeover to exorcise its colonial gaze.

The contributors to the book and the exhibition of “Unseen Photography from the 19th Century” are sensitive to the dilemma of even reproducing a photograph taken as part of the 19th-century propaganda effort to promote colonies as a force for good.

“Colonial photography is never neutral and is inherently problematic,” one writes.

Equally, they raise the question of whether nude pictures of women, perhaps prostitutes, perhaps women coerced by the establishment of the day, in suggestive poses should be exposed when it is impossible now to obtain the consent of their subjects.

On the other hand, exhibiting the hitherto unseen is the way a museum can open a dialogue on giving everyone agency.

If this all sounds too earnest, the FOMU’s vast collection of photographs includes moments of innocence, wonder and artistry. We marvel at hot air balloons and railway engines, scientific discoveries and early attempts to capture on camera the exquisite architecture of Brussels Grand-Place, since photographed countless times.

Barbara Lewis © 2026.

Unseen Photography from the 19th Century.

Published by Hannibal Books to accompany the eponymous exhibition at FOMU – Fotomuseum, Antwerp until March 1.

Photography – or painting with light, from the Greek roots of the word – is slightly younger than the country of Belgium.

It began in 1839 when Frenchman Louis Daguerre gave the world the daguerreotype process that could create a detailed single image. Around the same time in Britain, William Henry Fox Talbot created a negative image that could be used to make multiple positive prints.

Meanwhile, Belgium, which declared independence in 1830, became a forerunner in photographic identification and is home to the oldest preserved mugshots, dating from 1843.

As well as using photography to catch criminals, Belgium led the way in putting the technique to arguably criminal uses, including pornography and the wider abuse of power, which sadly finds an echo in today’s AI image manipulation.

Notoriously, photography was one of the means used to reinforce King Leopold II ‘s personal control of the Congo Free State, which he claimed as his private property from 1885 until 1908. Then, under intense international pressure, he handed control to the country of Belgium, and it became known as the Belgian Congo.

Working from the premise that museums, like the rest of the traditional establishment, have typically been highly selective in what they present to the world, the Fotomuseum in Antwerp, known as the FOMU, takes a soul-searching look into past crimes of omission and commission – or the underexposed versus the exposed.

The accompanying book, at once erudite and appealing, combines haunting reproductions of early photographs with elegant academic essays.

Colonialism is the central theme. It carries a wider significance of the more general exertion of the powerful over the oppressed, of men over women and children and of industrial magnates over their labour forces.

At the top of the power structure, Leopold II presided over Belgium’s 1897 contribution to the trend of world fairs, which he used as the means to publicise the supposedly civilising mission of his private colony and its economic opportunities.

When Belgium’s international exhibition was held in Brussels, a colonial section was built in Tervuren on the outskirts of the capital. A “human zoo” was created there in the form of a copy of an African village, where for the duration of the exhibition 60 Congolese people lived – and seven of them died.

From our 21st-century perspective, surviving photographs of the captive Congolese show people tragically displaced in an alien land, forced to wear alien clothes.

In the late 19th-century, however, the exhibition was hailed as a great success and the neoclassical building then named the Palace of the Colonies became a permanent museum.

It was closed in 2013 for a five-year renovation that was structurally necessary but also allowed for a makeover to exorcise its colonial gaze.

The contributors to the book and the exhibition of “Unseen Photography from the 19th Century” are sensitive to the dilemma of even reproducing a photograph taken as part of the 19th-century propaganda effort to promote colonies as a force for good.

“Colonial photography is never neutral and is inherently problematic,” one writes.

Equally, they raise the question of whether nude pictures of women, perhaps prostitutes, perhaps women coerced by the establishment of the day, in suggestive poses should be exposed when it is impossible now to obtain the consent of their subjects.

On the other hand, exhibiting the hitherto unseen is the way a museum can open a dialogue on giving everyone agency.

If this all sounds too earnest, the FOMU’s vast collection of photographs includes moments of innocence, wonder and artistry. We marvel at hot air balloons and railway engines, scientific discoveries and early attempts to capture on camera the exquisite architecture of Brussels Grand-Place, since photographed countless times.

Barbara Lewis © 2026.

By Barbara Lewis • added recently on London Grip, art, books, exhibitions, history, photography • Tags: art, Barbara Lewis, books, exhibitions, history, photography