Poetry review – DEFYING EXTINCTION: Charles Rammelkamp finds both resistance and acceptance in Amy Barone’s poems about mortality

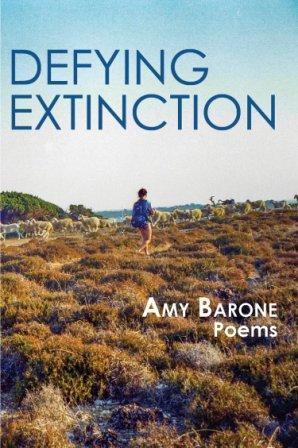

Defying Extinction

Amy Barone

Broadstone Books, 2022

ISBN: 978-1-956782-11-0

88 pp $25.00

Defying Extinction

Amy Barone

Broadstone Books, 2022

ISBN: 978-1-956782-11-0

88 pp $25.00

As the title of Amy Barone’s new collection of poems implies, her overarching theme is continuity, resistance to death and defeat, echoing Dylan Thomas’s famous line, “Rage, rage against the dying of the light.” But, even though her poetry is steeped in family, she speaks to humanity generally, not to a single person. It’s for the purpose of protecting our souls. (“Anima Protection” is the title of one of the five sections of the collection – in which the title poem, a tribute to the 146 garment workers who died in the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, is included.)

Barone’s scope is global, ranging from Australia to South America to Africa and New York, from Italy to Bermuda to Philadelphia, Mars and the moon. Yet, as in “Bronx Butterfly,” she can focus in on a Monarch butterfly chaotically, improbably, making its way through metropolitan traffic, as an illuminating metaphor –

Hoping poetry can restore us all,

and this flecked butterfly,

my guide on the journey,

will help lighten the weight.

Just as the butterfly defies extinction, so Barone writes admiringly about the maidenhair tree (symbol of love and longevity) whose relatives survived Hiroshima (“Twilight Flight”). She also speaks of the endangered Brown Bears that roam the Apennine Mountains (“Bearly”) and a rare yellow cardinal (“The Canary”) spotted in Alabama, both persevering, beating the odds. Or take the 17-year cicadas, Brood X, which reappeared in 2021 (“Cicada Shoals”). All survivors!

As their adults pass on,

the babes will burrow underground

and I dream of joining them in a 17-year sleep.

The first two sections of Defying Extinction, “Sacred Places” and “The Wild,” focus on these natural places and beings for which annihilation and devastation – and their opposite, rescue, preservation – are the setting and subject of this real-world drama. But even in the Heirlooms section the conflict and challenge are in our faces. “Hotel Seville” is a tribute to a hotel in New York’s historic Madison Square North neighborhood.

Sand-hued limestone lion heads and foliage

survived a century of noise and wear.

Its red brick façade stands tall in a city

of glass skyscrapers lacking heart.

Barone’s love of travel suggests her deep curiosity about the world in which we live. Her detail is often astounding, closely observed.

Defying Extinction includes a number of elegiac poems about her late mother and father. Indeed, section IV is titled “Love & Family.” “Handkerchiefs,” “The Bell Museum,” and “Nest” are a few poems in which various objects revive her mother’s memory with vivid poignance, and “Beauty Parlor” and “The Edge of Night” also bring her back in the memory of shared experiences. “Message,” “Paint Job” and “Secret Flight” tell of other reminders. “Rest in Peace?” takes place beside her parents’ graves. The memory of family, Barone seems to be telling us, provides another nourishment for the soul, another helmet to put on for the work of resistance.

The arts also provide ammunition that help us defy extinction. A handful of poems praise music as a restorative and nurturing art. “A Love Supreme” is a paean to a jazz musician. John Coltrane, McCoy Tyner, Elvin Jones are inspirations. “Queen of Tone” is a tribute to Abigail Ybarra, who made instruments for Fender Guitars for over half a century, enabling Jimi Hendrix, Eric Clapton and Joan Jett, among others, to make their distinctive sounds. “Piano Echoes” recalls the early days of Tin Pan Alley.

Music filled the alleys of New York’s West 28th Street.

Father of the Blues J.C. Handy and Scott Joplin wrote

catchy songs there in the early 1900’s.

Ragtime and jazz poured from saloons and halls.

Where “In the Good Old Summertime”

and “Give My Regards to Broadway” were born.

A universal language took root.

Walls to show biz success fell.

America’s sheet music trade thrived.

Barone elaborates other survival strategies, including poetry, the moon and the stars, and the “art of forgetting.” “Wizard-ess” is a clever extended metaphor that channels The Who’s “Pinball Wizard,” in which she compares herself to a pinball machine. “I used let them tilt me too low, bump me too hard.” Now she’s learned it’s all in the timing. “”Now I’m relaxing, resting my sharpened flippers.”

“Heavenly Park,” “Swimming on la Luna,” “Mars Bound,” “Lunar Love,” “Bardo,” and “Wonder” are some of the poems that look beyond the Earth for inspiration, to “pass over blue states, red states, too much talk” to “erect a life unfettered / by wires, rules, love, and reason.” It’s all a metaphor, of course, for the imagination. “Strawberry Moon” is a gorgeous meditation about the first full moon in June and an indictment of our smartphone-obsessed culture.

“Half Moon” is a short poem that is similarly intended to provide guidance, humorously undercutting religion in the process. She writes:

Come down from the cross.

Unglue your hands.

Bandage your neck.

Forgiveness is overrated.

Live well.

Don’t pay the ultimate price for

their trespasses.

While in several of her poems she does grieve about the pandemic and the lockdown, the cruel, pointless death, the deep mourning, in a sense Amy Barone’s poetry does go gentle into that good night, with grace, while cautioning us never to take existence for granted. We can find peace, she asserts, if we are willing to look for it. As she concludes in the final poem, “Dolce Far Niente,” a sort of post-pandemic psalm, a sacred song:

Recharge your smartphone –

freedom’s on the line.

Aug 4 2022

London Grip Poetry Review – Amy Barone

Poetry review – DEFYING EXTINCTION: Charles Rammelkamp finds both resistance and acceptance in Amy Barone’s poems about mortality

As the title of Amy Barone’s new collection of poems implies, her overarching theme is continuity, resistance to death and defeat, echoing Dylan Thomas’s famous line, “Rage, rage against the dying of the light.” But, even though her poetry is steeped in family, she speaks to humanity generally, not to a single person. It’s for the purpose of protecting our souls. (“Anima Protection” is the title of one of the five sections of the collection – in which the title poem, a tribute to the 146 garment workers who died in the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, is included.)

Barone’s scope is global, ranging from Australia to South America to Africa and New York, from Italy to Bermuda to Philadelphia, Mars and the moon. Yet, as in “Bronx Butterfly,” she can focus in on a Monarch butterfly chaotically, improbably, making its way through metropolitan traffic, as an illuminating metaphor –

Just as the butterfly defies extinction, so Barone writes admiringly about the maidenhair tree (symbol of love and longevity) whose relatives survived Hiroshima (“Twilight Flight”). She also speaks of the endangered Brown Bears that roam the Apennine Mountains (“Bearly”) and a rare yellow cardinal (“The Canary”) spotted in Alabama, both persevering, beating the odds. Or take the 17-year cicadas, Brood X, which reappeared in 2021 (“Cicada Shoals”). All survivors!

The first two sections of Defying Extinction, “Sacred Places” and “The Wild,” focus on these natural places and beings for which annihilation and devastation – and their opposite, rescue, preservation – are the setting and subject of this real-world drama. But even in the Heirlooms section the conflict and challenge are in our faces. “Hotel Seville” is a tribute to a hotel in New York’s historic Madison Square North neighborhood.

Barone’s love of travel suggests her deep curiosity about the world in which we live. Her detail is often astounding, closely observed.

Defying Extinction includes a number of elegiac poems about her late mother and father. Indeed, section IV is titled “Love & Family.” “Handkerchiefs,” “The Bell Museum,” and “Nest” are a few poems in which various objects revive her mother’s memory with vivid poignance, and “Beauty Parlor” and “The Edge of Night” also bring her back in the memory of shared experiences. “Message,” “Paint Job” and “Secret Flight” tell of other reminders. “Rest in Peace?” takes place beside her parents’ graves. The memory of family, Barone seems to be telling us, provides another nourishment for the soul, another helmet to put on for the work of resistance.

The arts also provide ammunition that help us defy extinction. A handful of poems praise music as a restorative and nurturing art. “A Love Supreme” is a paean to a jazz musician. John Coltrane, McCoy Tyner, Elvin Jones are inspirations. “Queen of Tone” is a tribute to Abigail Ybarra, who made instruments for Fender Guitars for over half a century, enabling Jimi Hendrix, Eric Clapton and Joan Jett, among others, to make their distinctive sounds. “Piano Echoes” recalls the early days of Tin Pan Alley.

Barone elaborates other survival strategies, including poetry, the moon and the stars, and the “art of forgetting.” “Wizard-ess” is a clever extended metaphor that channels The Who’s “Pinball Wizard,” in which she compares herself to a pinball machine. “I used let them tilt me too low, bump me too hard.” Now she’s learned it’s all in the timing. “”Now I’m relaxing, resting my sharpened flippers.”

“Heavenly Park,” “Swimming on la Luna,” “Mars Bound,” “Lunar Love,” “Bardo,” and “Wonder” are some of the poems that look beyond the Earth for inspiration, to “pass over blue states, red states, too much talk” to “erect a life unfettered / by wires, rules, love, and reason.” It’s all a metaphor, of course, for the imagination. “Strawberry Moon” is a gorgeous meditation about the first full moon in June and an indictment of our smartphone-obsessed culture.

“Half Moon” is a short poem that is similarly intended to provide guidance, humorously undercutting religion in the process. She writes:

While in several of her poems she does grieve about the pandemic and the lockdown, the cruel, pointless death, the deep mourning, in a sense Amy Barone’s poetry does go gentle into that good night, with grace, while cautioning us never to take existence for granted. We can find peace, she asserts, if we are willing to look for it. As she concludes in the final poem, “Dolce Far Niente,” a sort of post-pandemic psalm, a sacred song: