THE SECRET OF THE OLD RED PHONE BOOTH: Sarah Lawson is reminded of some children’s books from former generations

The old red phone booth on Lewisham Way is a great way to get rid of books. Someone might like them; this is a very mixed London neighbourhood and there are a couple of colleges nearby. I use it as my personal guilt-free wastepaper basket for books that I no longer want but can’t bring myself to throw away. I try not to be tempted to take any books out of this cooperative mini-library, because I am vainly trying to downsize.

The old red phone booth on Lewisham Way is a great way to get rid of books. Someone might like them; this is a very mixed London neighbourhood and there are a couple of colleges nearby. I use it as my personal guilt-free wastepaper basket for books that I no longer want but can’t bring myself to throw away. I try not to be tempted to take any books out of this cooperative mini-library, because I am vainly trying to downsize.

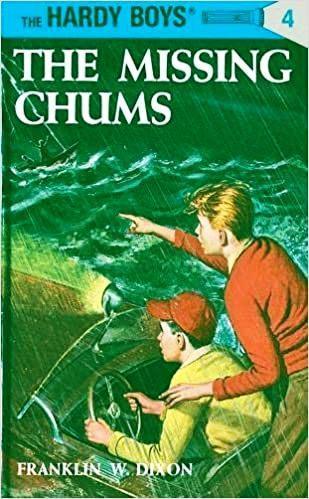

This time I was ditching some poetry pamphlets and out-of-date guide books to eastern Europe. I couldn’t help glancing over the other books—an random selection of current novels, classics, practical manuals, chunky magazines, children’s picture books, and the odd book in French or German. But suddenly I saw a strangely familiar book!

I hadn’t seen one of the Hardy Boys adventures since I outgrew them many decades ago. I even recognized the title of this one, early in the series, The Missing Chums. When I was reading it I had to ask my mother (my dictionary at the time) what “chums” meant. Now I checked the titlepage verso: Grosset and Dunlap, copyright 1928. I suddenly saw myself reading it as a child in suburban Indianapolis in about 1954, but what was this copy doing here in south London? Of course I took it home with me.

I had inherited three or four Hardy Boys books from my older brother and was quickly enchanted by the exciting derring-do of the boys, Joe, 15, and his brother Frank, 16. They were so much older than I was that they seemed the next thing to adults. The older one, at 16, could drive a car. They lived in far-away New Jersey on the Atlantic coast. Their father was Fenton Hardy, a noted private detective, and the boys, with a little help from their pals (“chums”, in fact), found their own cases to solve. Sometimes they cadged one from dad.

I couldn’t have realized then that the author, Franklin W. Dixon, was actually a syndicate churning out these novels to a formula, but I did notice that the books were nearly always 212 pages long. There were about thirty in the series then, and The Missing Chums was number 4. The crimes being investigated were light on violence. The bad guys were thieves or counterfeiters or fraudsters. They might be pirates or smugglers or even kidnappers. Nobody ever came to serious harm, although there was certainly a sense of danger and menace. The crooks might be armed but were invariably bad shots. There were creepy deserted houses; there were motorboats, iceboats, motorcycles, and cars. Sinister things happened at night as one watched from a hiding place. People might be tied up and then rescued. The chapters generally ended with a provocative cliff-hanger. By the last chapter the mystery was solved, the miscreants were in handcuffs, and Fenton Hardy was congratulating his sons and forgiving them for any trespasses on his professional work. Of course I had to be reminded more than once to come to the table for meals.

In suburban Indianapolis in 1954 the books were still in print but noticeably outdated in parts. The series had begun in 1927, and sometimes it showed. The books I read had all been written before I was born. Cars had running boards and side curtains, they whizzed along at forty miles an hour. I thought that was one of their charms. I had to ask my dictionary what “side curtains” were, and she knew from personal experience. (What later dictionary could ever offer this feature?) But the adventures were timeless. Bad guys, creepy houses, caves, sudden storms, flashlights at midnight, reliable parents, and good friends don’t date.

When I recently reread The Missing Chums, I found many features I remembered, including the eccentric and imperious Aunt Gertrude, who comes for an occasional visit with her cat, Lavinia. She is useful for comic relief and, in this case, when the boys want to be away from home overnight and their father is off catching robbers, but somebody needs to stay with their mother. The prose is not outstanding, but it races from one daring adventure to another. The vocabulary startled me a bit. Aged 10, could I have known the meaning of obdurate, recumbent, desultory, or fetid? Is this why I have such a vivid memory of needing urgent definitions from my mother? These books must have been meant to be educational. Why else would the writer have someone speaking sternly in the stern of a boat, if not to illustrate different usages? And who expects a 10-year-old to know what badinage means? The obvious answer is that 10-year-olds weren’t the target audience. As a child I never cared who the target audience was; if it was in print in English it was fair game.

Now it seems the series has been updated with mod cons and current vernacular. Mobile phones, recent cars, computers—the latest paraphernalia of boyhood detection. Presumably no one now exclaims “Good night!” and “mighty” is no longer a synonym for “very”. Indeed, some volumes in the series have been entirely rewritten with quite different plots while retaining the same titles! The language and references have been modernised. (I recall a reference in one of the books to “Hard-Hearted Hannah” that must have puzzled me at the time, but it was easy enough to get the general idea and skip the details.)

I think this updating is a mistake probably inspired by the sales department of later publishers. It amounts to a confession that their books are ephemeral trash rather than potential classics. Do you update Winnie-the-Pooh or The Wind in the Willows? No. Little Women or The Secret Garden? Does anyone care about old-fashioned expressions in them, except to regard them as charming and of their period? When the caterpillar in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland smokes a hookah, do you replace it with a pack of Marlboros or a vape kit? No, you do not. Does the unpunctual White Rabbit consult his smartphone? Unthinkable.

The Hardy Boys should exist in their mythical New Jersey city of Bayport with their running-boarded rumble-seated cars without any tinkering by modernisers. Anyway, they weren’t as out of date as all that. A few antiquated terms didn’t detract from the story. I sat reading them (the table lamp to my right, the cat dozing by my side in the big easy chair, my feet on the old ottoman), fascinated by the creepy houses, the secret codes, the desperate races against the clock, the last-minute foiling of the dastardly crooks.

“Yes, all right, I’m coming,” I would call out to my long-suffering dictionary forlornly trying to serve hot food.

Aug 3 2022

THE SECRET OF THE OLD RED PHONE BOOTH

THE SECRET OF THE OLD RED PHONE BOOTH: Sarah Lawson is reminded of some children’s books from former generations

This time I was ditching some poetry pamphlets and out-of-date guide books to eastern Europe. I couldn’t help glancing over the other books—an random selection of current novels, classics, practical manuals, chunky magazines, children’s picture books, and the odd book in French or German. But suddenly I saw a strangely familiar book!

I hadn’t seen one of the Hardy Boys adventures since I outgrew them many decades ago. I even recognized the title of this one, early in the series, The Missing Chums. When I was reading it I had to ask my mother (my dictionary at the time) what “chums” meant. Now I checked the titlepage verso: Grosset and Dunlap, copyright 1928. I suddenly saw myself reading it as a child in suburban Indianapolis in about 1954, but what was this copy doing here in south London? Of course I took it home with me.

I had inherited three or four Hardy Boys books from my older brother and was quickly enchanted by the exciting derring-do of the boys, Joe, 15, and his brother Frank, 16. They were so much older than I was that they seemed the next thing to adults. The older one, at 16, could drive a car. They lived in far-away New Jersey on the Atlantic coast. Their father was Fenton Hardy, a noted private detective, and the boys, with a little help from their pals (“chums”, in fact), found their own cases to solve. Sometimes they cadged one from dad.

I couldn’t have realized then that the author, Franklin W. Dixon, was actually a syndicate churning out these novels to a formula, but I did notice that the books were nearly always 212 pages long. There were about thirty in the series then, and The Missing Chums was number 4. The crimes being investigated were light on violence. The bad guys were thieves or counterfeiters or fraudsters. They might be pirates or smugglers or even kidnappers. Nobody ever came to serious harm, although there was certainly a sense of danger and menace. The crooks might be armed but were invariably bad shots. There were creepy deserted houses; there were motorboats, iceboats, motorcycles, and cars. Sinister things happened at night as one watched from a hiding place. People might be tied up and then rescued. The chapters generally ended with a provocative cliff-hanger. By the last chapter the mystery was solved, the miscreants were in handcuffs, and Fenton Hardy was congratulating his sons and forgiving them for any trespasses on his professional work. Of course I had to be reminded more than once to come to the table for meals.

In suburban Indianapolis in 1954 the books were still in print but noticeably outdated in parts. The series had begun in 1927, and sometimes it showed. The books I read had all been written before I was born. Cars had running boards and side curtains, they whizzed along at forty miles an hour. I thought that was one of their charms. I had to ask my dictionary what “side curtains” were, and she knew from personal experience. (What later dictionary could ever offer this feature?) But the adventures were timeless. Bad guys, creepy houses, caves, sudden storms, flashlights at midnight, reliable parents, and good friends don’t date.

When I recently reread The Missing Chums, I found many features I remembered, including the eccentric and imperious Aunt Gertrude, who comes for an occasional visit with her cat, Lavinia. She is useful for comic relief and, in this case, when the boys want to be away from home overnight and their father is off catching robbers, but somebody needs to stay with their mother. The prose is not outstanding, but it races from one daring adventure to another. The vocabulary startled me a bit. Aged 10, could I have known the meaning of obdurate, recumbent, desultory, or fetid? Is this why I have such a vivid memory of needing urgent definitions from my mother? These books must have been meant to be educational. Why else would the writer have someone speaking sternly in the stern of a boat, if not to illustrate different usages? And who expects a 10-year-old to know what badinage means? The obvious answer is that 10-year-olds weren’t the target audience. As a child I never cared who the target audience was; if it was in print in English it was fair game.

Now it seems the series has been updated with mod cons and current vernacular. Mobile phones, recent cars, computers—the latest paraphernalia of boyhood detection. Presumably no one now exclaims “Good night!” and “mighty” is no longer a synonym for “very”. Indeed, some volumes in the series have been entirely rewritten with quite different plots while retaining the same titles! The language and references have been modernised. (I recall a reference in one of the books to “Hard-Hearted Hannah” that must have puzzled me at the time, but it was easy enough to get the general idea and skip the details.)

I think this updating is a mistake probably inspired by the sales department of later publishers. It amounts to a confession that their books are ephemeral trash rather than potential classics. Do you update Winnie-the-Pooh or The Wind in the Willows? No. Little Women or The Secret Garden? Does anyone care about old-fashioned expressions in them, except to regard them as charming and of their period? When the caterpillar in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland smokes a hookah, do you replace it with a pack of Marlboros or a vape kit? No, you do not. Does the unpunctual White Rabbit consult his smartphone? Unthinkable.

The Hardy Boys should exist in their mythical New Jersey city of Bayport with their running-boarded rumble-seated cars without any tinkering by modernisers. Anyway, they weren’t as out of date as all that. A few antiquated terms didn’t detract from the story. I sat reading them (the table lamp to my right, the cat dozing by my side in the big easy chair, my feet on the old ottoman), fascinated by the creepy houses, the secret codes, the desperate races against the clock, the last-minute foiling of the dastardly crooks.

“Yes, all right, I’m coming,” I would call out to my long-suffering dictionary forlornly trying to serve hot food.