Poetry review – THE PEREGRINE FALCONS OF YORK MINSTER: Alwyn Marriage finds a “delicious mixture of humour and pathos” in Carole Bromley’s collection

The Peregrine Falcons of York Minster

Carole Bromley.

Valley Press, 2020

ISBN 978-1-912436-47-7

76 pages, £10.99.

The Peregrine Falcons of York Minster

Carole Bromley.

Valley Press, 2020

ISBN 978-1-912436-47-7

76 pages, £10.99.

I have long been an admirer of Carole Bromley’s work, for the wisdom, sensitivity and wit so consistently displayed in her poetry. As it is only a year since Calder Valley published Bromley’s powerful pamphlet about her illness and hospitalisation, Sodium 136, I wondered briefly if a collection coming so close on its heels might show signs of undue haste. However, I need not have feared, for the poems in this new collection are as rich and strong as ever. Bromley is well-known for her poetry for children, and it is delightful to find some of the charm and zany humour of her children’s poems sparkling in this new adult collection.

Before looking at the poems in more detail, I should like to comment on the organisation of the collection. A poet of less maturity and experience than Bromley might be tempted to throw in all their best poems, higgledy piggledy, particularly the ones that have achieved some measure of success in competitions or major journals. What Bromley offers, on the other hand, is a model of an intelligently ordered collection. There are no random jumps of subject matter, and each poem leads gently on to the next with a satisfying logic.

For example, poems about birds end with “Red Kites at Harewood”, then move effortlessly from that bird to the poet’s grandson flying his kite, before widening the focus to cover other family members. These lead to reminiscences of Bromley’s childhood, and thence to her relationship with her mother. Her mother is now dead, so it is a small move to pass on to other deaths, then spread out to travel, other characters and finally poems about art and literature.

Among the particular qualities that make Bromley’s work so attractive is her ability to say a great deal in few words. In “Homing” (page 10), for instance, we read of the boy, Steven: ‘his voice steady,/no trace of a stammer’. This succinctly suggests to us, without it being stated, that Steven normally does have a stammer, and goes on to hint, in the words ‘his hand/ with its bitten nails’, at the social difficulties that can cause for a child. The same gracious tact is displayed in a poem about an uncle with a shady history, “Uncle Arnold”:

I only knew about Arnold from whisperings

before my dad took the train to Durham on Saturdays

and afterwards never told us where he'd been. (p43)

This gift for understatement is also used to effect in “My case”, which describes the poet’s suitcase failing to turn up on the carousel after a journey. Eventually she leaves the airport without her luggage,

I hail a taxi, feeling oddly weightless,

my knickers gone, my six ironed T-shirts. (p40)

In contrast to such subtle suggestion is the meticulous detail to be found in other poems, such as in “Saltburn” on page 14. Here we have a picture of the poet’s grandson running through Saltburn while flying his kite. As we watch the boy running, some family history is revealed:

towards the town where his great-great-grandpa

built the whole High Street

and lived at number 129 from where

you could cut through to the beach

carrying a bucket for sea-coal.

The camera then pans back to the boy still running with his kite, now over the sands:

away from the pier and the cliff lift

and the flapping windbreak,

away from the candy-floss and ice cream,

away from the day trippers

towards the still winding gear

on his skinny, sparrow's legs,

the great bird casting its shadow

over the long, ribbed sand.

Memories of the poet’s own childhood include the graphic picture of the difficulty of letting go of the wall in the deep end of the swimming pool when she was 11 (“Beverley Baths”, page 20). In this short, ten-line poem, the poet evokes all the fear and uncertainty of an eleven-year-old, and brought back to me memories of my own terror of being made to jump into the deep end of a swimming pool as a small child, even when I was quite a good swimmer. Although so compact, I feel that this poem is also something of a metaphor for writing poetry.

Not all memories are happy, and Bromley is ruthlessly honest about her difficult relationship with her mother, painting a sweet-sour picture. “After” (page 27) describes the common experience of bereavement, where the faults and frailties of the deceased gradually fade, leaving room for older, more positive memories; and in “Ros’s Frosty Strawberry Squares” (page 29), there is the poignant moment when tears of grief are suddenly released at the sight of her mother’s handwriting:

I cry for the days of Frosty Strawberry Squares,

for your brown ink, your neatly rounded 'a's

your '1 pkg. Dream topping', for the thought

of you in the old kitchen 'stirring occasionally'.

There are other poems which deal with grief, either in childhood, when a schoolfriend dies, or in adulthood when she loses her friend, Helen Cadbury. While some of the poems are dark, others, such as “Bumping into John Lennon” (page 41), verge on the surrealist.

There are so many delights in this collection. I enjoyed the delicious mixture of humour and pathos in “I have been thinking”, in which a spider gets trapped in the printer, two of his articulated legs emerging with the sheet of a printed poem. “Go ahead, I’m listening” turns out to be a conversation with Siri (page 63); and “The New Mother” is an unusually successful found poem.

Other themes in the book include a return to her illness and time in hospital, with some of the poems from Sodium 136 given another airing here; a section on art, including Gwen John, Chagall and Stanley Spencer; and a series of poems based on literature. In this latter section, which includes the Wordsworths, Jane Eyre, David Copperfield, Adam Bede and Middlemarch, I felt that some explanatory notes would not have gone amiss. It is important in each case that the reader understands the literary references, and the complete lack of guidance in this area could be seen as unhelpful.

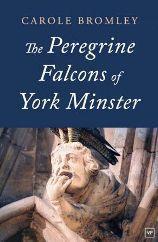

If I have a slight reservation about this book – and it is only slight – it is with the title. In itself, The Peregrine Falcons of York Minster is an extremely attractive title, further enhanced by the cover illustration of one of the gargoyles that grace the minster, so I can quite understand why Bromley chose it. I feel, however, that it would be a huge shame if people did not buy the book because they mistakenly thought all the poems were of only local interest to York Minster. I very much hope everyone realises that there is no such limitation in the poetry, because this book deserves to be bought and enjoyed widely.

Alwyn Marriage

Dec 17 2020

London Grip Poetry Review – Carole Bromley

Poetry review – THE PEREGRINE FALCONS OF YORK MINSTER: Alwyn Marriage finds a “delicious mixture of humour and pathos” in Carole Bromley’s collection

I have long been an admirer of Carole Bromley’s work, for the wisdom, sensitivity and wit so consistently displayed in her poetry. As it is only a year since Calder Valley published Bromley’s powerful pamphlet about her illness and hospitalisation, Sodium 136, I wondered briefly if a collection coming so close on its heels might show signs of undue haste. However, I need not have feared, for the poems in this new collection are as rich and strong as ever. Bromley is well-known for her poetry for children, and it is delightful to find some of the charm and zany humour of her children’s poems sparkling in this new adult collection.

Before looking at the poems in more detail, I should like to comment on the organisation of the collection. A poet of less maturity and experience than Bromley might be tempted to throw in all their best poems, higgledy piggledy, particularly the ones that have achieved some measure of success in competitions or major journals. What Bromley offers, on the other hand, is a model of an intelligently ordered collection. There are no random jumps of subject matter, and each poem leads gently on to the next with a satisfying logic.

For example, poems about birds end with “Red Kites at Harewood”, then move effortlessly from that bird to the poet’s grandson flying his kite, before widening the focus to cover other family members. These lead to reminiscences of Bromley’s childhood, and thence to her relationship with her mother. Her mother is now dead, so it is a small move to pass on to other deaths, then spread out to travel, other characters and finally poems about art and literature.

Among the particular qualities that make Bromley’s work so attractive is her ability to say a great deal in few words. In “Homing” (page 10), for instance, we read of the boy, Steven: ‘his voice steady,/no trace of a stammer’. This succinctly suggests to us, without it being stated, that Steven normally does have a stammer, and goes on to hint, in the words ‘his hand/ with its bitten nails’, at the social difficulties that can cause for a child. The same gracious tact is displayed in a poem about an uncle with a shady history, “Uncle Arnold”:

This gift for understatement is also used to effect in “My case”, which describes the poet’s suitcase failing to turn up on the carousel after a journey. Eventually she leaves the airport without her luggage,

In contrast to such subtle suggestion is the meticulous detail to be found in other poems, such as in “Saltburn” on page 14. Here we have a picture of the poet’s grandson running through Saltburn while flying his kite. As we watch the boy running, some family history is revealed:

The camera then pans back to the boy still running with his kite, now over the sands:

Memories of the poet’s own childhood include the graphic picture of the difficulty of letting go of the wall in the deep end of the swimming pool when she was 11 (“Beverley Baths”, page 20). In this short, ten-line poem, the poet evokes all the fear and uncertainty of an eleven-year-old, and brought back to me memories of my own terror of being made to jump into the deep end of a swimming pool as a small child, even when I was quite a good swimmer. Although so compact, I feel that this poem is also something of a metaphor for writing poetry.

Not all memories are happy, and Bromley is ruthlessly honest about her difficult relationship with her mother, painting a sweet-sour picture. “After” (page 27) describes the common experience of bereavement, where the faults and frailties of the deceased gradually fade, leaving room for older, more positive memories; and in “Ros’s Frosty Strawberry Squares” (page 29), there is the poignant moment when tears of grief are suddenly released at the sight of her mother’s handwriting:

There are other poems which deal with grief, either in childhood, when a schoolfriend dies, or in adulthood when she loses her friend, Helen Cadbury. While some of the poems are dark, others, such as “Bumping into John Lennon” (page 41), verge on the surrealist.

There are so many delights in this collection. I enjoyed the delicious mixture of humour and pathos in “I have been thinking”, in which a spider gets trapped in the printer, two of his articulated legs emerging with the sheet of a printed poem. “Go ahead, I’m listening” turns out to be a conversation with Siri (page 63); and “The New Mother” is an unusually successful found poem.

Other themes in the book include a return to her illness and time in hospital, with some of the poems from Sodium 136 given another airing here; a section on art, including Gwen John, Chagall and Stanley Spencer; and a series of poems based on literature. In this latter section, which includes the Wordsworths, Jane Eyre, David Copperfield, Adam Bede and Middlemarch, I felt that some explanatory notes would not have gone amiss. It is important in each case that the reader understands the literary references, and the complete lack of guidance in this area could be seen as unhelpful.

If I have a slight reservation about this book – and it is only slight – it is with the title. In itself, The Peregrine Falcons of York Minster is an extremely attractive title, further enhanced by the cover illustration of one of the gargoyles that grace the minster, so I can quite understand why Bromley chose it. I feel, however, that it would be a huge shame if people did not buy the book because they mistakenly thought all the poems were of only local interest to York Minster. I very much hope everyone realises that there is no such limitation in the poetry, because this book deserves to be bought and enjoyed widely.

Alwyn Marriage