*

The Autumn 2020 issue of London Grip New Poetry features:

*Zoe Brooks *Colin Pink *Tony Beyer *Leona Gom *Daniel Bennett *James Roderick Burns

*Jack Houston *Tom Phillips *Moya Pacey *Mary Franklin *Curtis Brown *Peter Kenny

*Angela Kirby *Kathleen McPhilemy *Ruth Valentine *Marie Dullaghan *Molly Burnell *Tanner

*Jane McLaughlin *Jennifer Johnson *Mary Robinson *Marion McCready *Fizza Abbas

*Bethany Rivers *Nancy Mattson *Jane Kirwan *Julia Duke *Phil Connolly *Pascal Fallas

*Alison Campbell *Shikhandin *Robert Nisbet *Rosemary Norman *Robin Houghton

*Sarah James *Ian C Smith *Fraser Sutherland *Phil Kirby *Stuart Henson *Emma Neale

Copyright of all poems remains with the contributors. Biographical notes on contributors can be found here

London Grip New Poetry appears early in March, June, September & December

A printer-friendly version of this issue can be found at

LG New Poetry Autumn 2020

SUBMISSIONS: please send up to THREE poems plus a brief bio to poetry@londongrip.co.uk

Poems should be in a SINGLE Word attachment or else included in the message body

Our submission windows are: December-January, March-April, June-July & September-October

Editor’s notes

Welcome to the second – but probably not the last – posting of London Grip New Poetry produced entirely in the shadow of the Covid-19 pandemic. The virus may not figure explicitly in many of the poems but its presence probably explains a note of foreboding that runs through this issue. We begin with large-scale themes of totalitarian dictatorship but soon move to more personal and domestic territory. Even here however the topics are darkish: reflections on memory & mortality; relationships under strain; cross-cultural tensions; struggles of growing up. And we end this issue with a handful of film noir vignettes. What these varied poems have in common as that they are all engaging, well-crafted and perceptive. It is gratifying that so many gifted poets are willing to entrust their work to us; and it has been a far from easy task to make the final selection that is now in your hands/on your screen

Welcome to the second – but probably not the last – posting of London Grip New Poetry produced entirely in the shadow of the Covid-19 pandemic. The virus may not figure explicitly in many of the poems but its presence probably explains a note of foreboding that runs through this issue. We begin with large-scale themes of totalitarian dictatorship but soon move to more personal and domestic territory. Even here however the topics are darkish: reflections on memory & mortality; relationships under strain; cross-cultural tensions; struggles of growing up. And we end this issue with a handful of film noir vignettes. What these varied poems have in common as that they are all engaging, well-crafted and perceptive. It is gratifying that so many gifted poets are willing to entrust their work to us; and it has been a far from easy task to make the final selection that is now in your hands/on your screen

Michael Bartholomew-Biggs

London Grip poetry editor

Forward to first poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Zoe Brooks: Perhaps

That Easter

there were angels everywhere,

electric in the air,

a frisson of freedom,

a lamentation of song.

Perhaps it was the poet president

racing through marble halls

on a child's tricycle,

arriving at meetings

with a squeak and a crash;

perhaps it was that cold spring

wreathing the statues

with garlands of mist,

a spring that had been so long coming,

arriving only with a jingle of keys;

perhaps it was the candles

guttering in Wenceslas Square,

tears bejewelling the flowers with ice,

the women bowing before

the black and white photograph,

that made us believe

that this time history would not

repeat its cruelties,

that Prague's angels would not

prove to have leaden wings.

And there I was,

so obviously alien

that I walked

in the middle of the pavement,

without looking over my shoulder.

In the warm light of Cafe Slavia,

drunk on long black coffee,

I asked about the future.

And the answer was always the same –

“Perhaps.”

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Colin Pink: The Problems of Philosophy

after Bertrand Russell

The table I write at appears solid, smooth and polished;

reflections of light glow white on its surface. If I turn

my head the colours change, the highlights skate across

the top; one edge looks longer but isn’t. Depending on

your point of view it all looks different. To the painter

these things are important. Russell’s elegant prose claims

we always experience a veil of appearances, never reality;

and to make it sound scientific he calls it ‘sense data’.

That world seems to be reliable, dependably the same,

tomorrow as it was today. And yet, we’re like chickens

who everyday are fed by the farmer at the same time.

But one day instead of feeding the chickens he wrings

their necks. This is known as the problem of induction.

And not a lot of chickens know that. And neither did I.

Colin Pink: Never Accept Words from Strangers

Did you pack these words yourself? Has anyone

given you words to carry for them? Have you left your

vocabulary unattended at any point in your journey?

As they snap on the rubber gloves to probe,

persuade and intimidate you realise

you’re costive with words that aren’t yours.

Don’t accept words from strangers

however well-meaning they appear.

Remember: Cui bono? Cui bono?

Remove their hand from your crotch/purse/mouth;

rip out their fake smiles with your teeth.

There’s violence folded within everyday phrases:

Take Back Control,

Economic Migrants,

Make [INSERT NATION HERE] Great Again.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Tony Beyer: Turn

the new leader’s dead eyes

don’t change expression

while the question is asked

or as he intones his answer

the impression this gives

is that anything he says

must be obvious anyway

to anyone with any sense

he’s not interested in those

who aren’t listening to him

it’s the troubled and fearful

of change who are his target

unless it’s the change back

he’s already announced

to perks and entitlements

for those who favour him

his aim is to control a

population more than half

of whom won’t concern him

once the votes are in

he needs losers to help

his winners feel affirmed

withholding the charitable

glad hand for photo ops

snipping open the ribbon

on a track through the bush

or cannily distributing

cosy appointments

these are the purposes

for which his upright carriage

his impeccable menswear

were calculated

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Leona Gom: 62 Billionaires

62 billionaires own as much wealth as half the world’s population

—Oxfam report, 2016, cited in Beyond Banksters, by Joyce Nelson

They could all fit into your house,

these owners of the world. Imagine them

there, not that comfortable and not exactly

friendly but agreeing to give it a try. But

what could you talk about? The weather?

Of course they own that, too, so

the subject is not as safe as it sounds.

And what as a good hostess could you possibly

offer them? Even a glass of water already belongs

to them in a way you can barely understand.

The ones that talk might be willing to answer

a question or two about their favourite possessions:

a favourite wife, an island, a sled, a government.

They might even express a certain bewilderment

at how they have become this rich. It seemed

to take no effort at all, they admit. At some point

it was so easy to buy the laws and the lawmakers

they could do it in their sleep, and they did.

Perhaps they even blame you, wondering why

you did not stop them. Now, of course,

it’s too late. They murmur about algorithms

and portfolios beyond their control.

When they leave they will be polite.

They will smile, collusively, across the room

at each other. At you the smile is something

else, but not pity, not any more. Pity is

always an early divestiture, and it, too,

is no longer under their control.

Leona Gom: The Lenins

—after reading Budapest, by Rick Steves

Back to back now or facing each other

across the memorial Budapest park,

moved from their pedestals in city squares

and courtyards, from government buildings,

to this graveyard of communist statues, stately

or with arms raised, looking up, looking down,

holding a flag, a book, a gesture, brought here

while the nineties hammered their century shut.

Overnight gone from honour to disdain,

not pulled down in retribution but

parked in a garden of broken ideas,

not turned to honest rubble but to warnings,

to kitsch for the tourists happy to pay

and take their comical selfies and get

back on the bus to capitalism.

What do the Lenins murmur to each other in

the winter evenings when the park is closed?

What messages of regret and sadness?

Stalin, they whisper, you there in the east

corner, all your fault, you insane bastard,

who knows where we might be now

without you. The snow falls into

all his death, all that silence.

Back to back now or facing each other

across the memorial Budapest park,

moved from their pedestals in city squares

and courtyards, from government buildings,

to this graveyard of communist statues, stately

or with arms raised, looking up, looking down,

holding a flag, a book, a gesture, brought here

while the nineties hammered their century shut.

Overnight gone from honour to disdain,

not pulled down in retribution but

parked in a garden of broken ideas,

not turned to honest rubble but to warnings,

to kitsch for the tourists happy to pay

and take their comical selfies and get

back on the bus to capitalism.

What do the Lenins murmur to each other in

the winter evenings when the park is closed?

What messages of regret and sadness?

Stalin, they whisper, you there in the east

corner, all your fault, you insane bastard,

who knows where we might be now

without you. The snow falls into

all his death, all that silence.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Daniel Bennett: The Panda

The sounds of the house begin above him,

a family waking. He thinks of Stalin

preferring a sofa to a presidential bed,

of the ace of pentacles gleaming

from the apocrypha of a bookshelf

of the bottle of Cahors he drank last night,

a black wine, dark as a tarot reader's smile.

He winds the blanket tighter, but sleep

has vanished for another day.

Stalin lay dead for days because lackeys

wouldn't wake him. Lucky Stalin.

He considers how all things are rare

and fleeting: power, ambition, sleep,

the ephemera that crams inside a head,

even the emptiness that ensues

when loves disappears. Already,

this day is spoiled.

Through the glass door

of the lounge, his daughter watches.

For how long he can't tell. Her gaze moves

from the space he occupies, back upstairs,

towards his former habitat. A radio sounds,

a song about hips meeting, kisses,

the rest. He lifts himself with the blanket

wrapped about him, smiles and waves,

because captivity should be safe for all.

The girl retreats. He sees his reflection

in the shine on glass: his pot belly,

eyes dark from sleep. New footsteps

press on the stairs, subtle and hesitant.

He begins to dance across the cage,

his claws scraping on squeaking boards,

his tongue probing a shred of green bamboo.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

James Roderick Burns - haiku

Two dogs

boxing in the park –

dusting of blossoms

Muggy day –

beyond blackbird hedge,

a patient cat

At the insect’s

approach, a lilac-bush

begins to quiver

Hard wind –

pawnbroker’s eagle

itches to fly

Sun-warmed rat,

war-memorial plinth

all to himself

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Jack Houston: sparrows

there’s at least corn

flakes a dozen

mixed nuts in the fish

fingers bushes near

the end bananas

of our avocados flats

flitting coffee goat’s

cheese in and those

little yoghurts out

of the kids like

the foliage splitting

whatever they’re

Marmite doing between

each washing up other

food probably liquid

the finding of

the search for olive

sustenance oil there one

mustard moment gone

the raisins next I

haven’t time to stand

and oat cakes

watch them though

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Tom Phillips: Unfair assumptions about pigeons

The pigeons strut across what’s left of the lawn

like generals or politicians inspecting frontline mud

on the day after the last shot sounded in a war.

They’ll glean nothing from this compacted earth.

A smaller, prouder finch has its tail feathers up.

It knows when it’s under threat and does its best

to make a voice heard above mechanical coos

from the frog-marching, land-grabbing pigeons.

As if in an allegory, our downstairs neighbour appears.

He plugs a hosepipe onto the garden tap and turns

a sudden spurt of water over parts of the yard

he’s doing his best to cultivate despite the birds.

Later, when the sun slides down apartment facades,

bats will hurl their soft, dark bodies through free air.

10 April 2019, Sofia

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Moya Pacey: Birders

Instead of smelting steel or driving

forklifts at the port, men are buying bird

books, spotting, making blogs, competing.

Last week, Pete scored a willow warbler.

Harry beat that with an orange-breasted

whinchat. Wildlife Centres springing

up where smokestacks once belched

hot air and muck. Dads and grandads

walking lads out over marsh,

telling tales of birds’ long journeys.

Places where they fed, watered,

rested in sanctuaries now disappeared.

In the hide, men whisper names—

shoveler, pochard, lapwing,

redshank—once a glossy ibis.

The lads are their apprentices.

Men help them to adjust the lenses

of binoculars, so that when

they close one eye and squint,

they see

the world changed

for birds and men.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Mary Franklin: Lost and Found

Clearing space in the attic

for another box of books

the skirling of swallows

under gathering clouds

warns me of the onset

of a summer storm. I lean

an arm on the windowsill,

watch a squirrel scurry up

three-sided, blue-green needles

of a tamarack, then vanish

among its mysterious foliage.

My foot touches something odd.

A child’s memory guides me

to a voice I loved that for years

I have heard only in dreams

and I stare down at an old

vinyl record, the label torn,

destroyed by damp and time.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Curtis Brown: Between Lines

Should I read the lines of your life I fear I may

neither find myself amongst them nor indeed

between them despite having written them

with you throughout our many years so I sing

my own song to you as we embrace my tears

falling down your back onto the horizon

shimmering a mirage of salt water yet I count

this painful blessing more favourable than the fear

of a stranger in your eyes as they gaze upon

my face and search for it between the fading lines...

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Peter Kenny: The door in the wall

Orange bollards, the bus gridlocked.

From its top deck I see a plane tree’s shadow;

how distinct leaf shapes shoal over a wall

of whitewashed brick, and a green door.

I fox this page with a memory: a summer

when I, a boy from the flats, trespassed

through bramble, stingers and Bramley trees,

into private gardens. I climbed on damp,

back-broken sheds, parachuting bindweed trumpets

into the spiders’ Germany of flowerpot towers

and wood-loused tenements of rotten wood.

I tried every door, hoping to steal into a story,

a walled garden perhaps, where a woman

is waiting with the book of me open on her lap,

my choices forking through its pages.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Angela Kirby: Rain

Sometimes in those long wet northern summers

a solitary child wanders out into the sodden garden

and makes her way through a dripping arch

of golden hops to the long wood which only a few

short weeks ago she’d seen awash with bluebells.

Now she finds that one well-hidden clearing

from which to see a thin grey swab of sky, and lying

on the damp earth she offers herself up to the rain

till all her lonely pain is washed away and she feels

whole again, redeemed by this secret baptism.

Angela Kirby: 3 AM

no moon, no stars, no sirens

no cat yowls, no dog howls

only a small clear voice persists

‘On whose walls will your pictures

hang, where will two thousand books

find home, who will then dust

the Staffordshire, Chelsea, Spode

Crown Derby, Famille Rose

and those Meissen figurines?’

Lying here, one thing’s for sure -

when I go – which may be soon

I’ll no longer know nor care

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Kathleen McPhilemy: Months of Sundays

It was not (to start again) what one had expected.

What was to be the value of the long looked forward to

Long hoped for calm, the autumnal serenity

And the wisdom of age? T S Eliot, East Coker

Desultory whistling from the garden next door

the rumble of a neighbour’s lawnmower:

Sunday again;

Confined to my category

I can hardly be bothered to name the days.

I don’t think I can get used to this.

For all its imperfections

I miss

the world we had.

When I considered age and death

I expected to grow old

in the world I knew;

I thought when I died

I would leave a me-shaped space

and others would carry on

around an emptiness

they recognised

accepted

and remembered me by.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Ruth Valentine: At Mortlake

For ten minutes I was not living my own life

though somebody stepped down

from the train to the platform it was

a day in spring

not raining not quite sunny

somebody crossed to the far side of the line

however you cross there waited

a gap between lorries

threaded herself into the alleyway

and out onto the towpath

not flooded that afternoon

then at the gate

into the cemetery somebody became

me but I tell you I was not

living that life

in those minutes I was walking

back along the river towards the city

downriver to Kew

or sitting

in the sun on the green

watching a small girl run after a pigeon

or I was hitting someone or fucking someone

in the non-existent station underpass

or writing a poem or lying in bed with you

half asleep in your arms

I wish I had been lying

in your arms those lost minutes

the doctor says

sooner or later I will lose much more

Ruth Valentine: Cloths Used For Oiling May Spontaneously Combust*

along with elderly shopkeepers in Dickens,

hayricks, things focussed through a piece of glass,

people in lockdown.

Spontaneous combustion: a useful skill

we all should aspire to. The fat cremation fees

you'd save your estate! And think of the satisfaction

of selecting when and where: the local park,

that dress shop where they looked at you like dirt,

which you'll be once the flames die down. Or Downing Street.

I'm rehearsing already: sitting out in the sun,

overheating the bedroom.

I just need to know I can, when the time comes:

a fortnight of driving rain, say, or politicians

claiming Everything's under control, and smiling, smiling.

*warning on a bottle of Danish furniture oil

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Marie Dullaghan: Smoking

We waited long minutes under dark clouds.

When the time came, my sister could not enter,

stood instead among the screened rubbish bins.

My son went to her, placed a lit cigarette

between her lips.

I broke protocol; entered the building first.

Those who had gathered, followed, awkward, hesitant.

In the centre of the room, a flutter like bird wings

in my chest. Anxious.

Oh God! How alike these cousins!

I never noticed – the beard, the nose, the hair,

the younger outside with his aunt,

cigarette smoke struggling up through damp air,

the other in here, godless voices

in unfamiliar prayer surround his coffin.

Then the rain.

Loud fat drops, beating the roof, the doors, the windows.

Strangers in black suits fastened the lid.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Molly Burnell: Fragility

You look up from your cigarette

as a black horse gallops by, burning

a flickering orange-yellow tail

into the dark, into your eyes.

A mane of flailing flames

upon its veined neck,

disjointed wisps of fire-tips

dying into sooty air.

You stand and you watch,

before relinquishing the paper

pinched between your index

and middle, like it isn’t there,

letting it fall onto a paper path

and scatter its glowing ashes

on the wind, into paper trees,

paper grass and your paper self.

Every edge curls into the dark

because everything is thin

and prone to catching fire,

falling to tiny pieces

at the slightest touch, the caressing

and consuming

of yellowing fingers

and blackening nails.

Molly Burnell: Secrets

Tear me to secrets

like I’m paper

etched with words

that won’t ink

out of my mouth

onto the air.

You can chew

on an untasted cut

of me in your head,

over and over;

a slice of stale bread

broken into smaller,

easier-to-swallow chunks.

But if you do swallow

and the taste brings tears,

don’t feed me

to the ducks scattered

through the park like crumbs,

or the homeless man

swept into the doorway

of the boarded-up

Chinese takeaway,

on your walk back

to your parents.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Tanner: you have to give her that

she’d be crying

when she’d tell you

you’re too short

or you don’t make enough money

or you’ll never be a writer

she’d be crying

as she said these things

and she’d be nodding

and to everyone else in the bar

it would look like

she was agreeing with

something hurtful

you were saying

to her

and when a couple of white knights

who’d been watching

would come over

she’d look away

embarrassed

inadvertently showing them

the walnut bruise on her cheekbone

she got from falling down drunk

and then she wouldn’t say

anything.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Jane McLaughlin: Way In

please enter your Pin number

please enter your password

please enter your username

please enter the second, sixth and eighth letters of your memorable word

please enter your grandmother’s shoe size

please enter your last cholesterol reading

please enter the name of your window cleaner’s wife

please say five Hail Marys and one Our Father

sorry your details have not been recognised

please click on this link to reset your password

please select a memorable question

what is your mother’s maiden name?

what is the name of your first school?

who is the muse of lyric poetry?

in what constellation is the star Deneb?

who wrote the Almagest?

why are you bothering to answer these questions?

why do you want to spend your money on products

produced by slave labour on the other side of the world?

please enter your email address

sorry that email address is not recognised

please register your details here to set up a new account

sorry that address is already in use

please enter your username

sorry that name does not exist

sorry your identity has been deleted from cyberspace

Abandon hope all ye who fail to enter here

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Jennifer Johnson: Passages

In this coastal town

white poverty protects itself

with flags and dogs.

Visitors climb to the fort

that guarded against strangers

for millennia, look down

on ferries that feed this port.

Underneath the castle

lies chalk of the sort

teachers taught and

frightened me with,

rock worm-eaten

by defensive passages

carved out in countless wars.

These chalk tunnels

dig into my memory,

my childhood obscured

by Sudanese sandstorms.

A plane simply flew my family

into clearer weather,

first to Malta, then London.

Are those head-scarfed women

sitting on the bench

tourists or have they made

one of those epic journeys

you see on the news

crossing shifting sand dunes,

Mediterranean waves?

It makes no difference

to the tattooed drunk pulled

by his metal-chained fighting dog.

He swears into the coastal gale

that takes away his voice.

The women put on dark coats,

cover their bright clothes.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Mary Robinson: Beirut

for Josie

The trees would have been greening up impossible places

in empty houses and on roof tops

it would have been spring in the city but on the mountains snow

she would have come at the same moment you took out your phone

outside the French café just down from the Armenian church

with its pock-marked yellow stone and rose window

she would have been standing behind me

in an ankle-length robe patterned in gold and purple

the hem soiled and frayed by the Beirut streets

strands of ash-grey hair escaped from her scarf

her knuckles poked through her tissue skin

and one eye was clouded over like marble

she would have been carrying a child.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Marion McCReady: Her Hair is a Landscape of its Own

for Ruby

I am scaling the cliff face of her hair to reach her -

my summit-daughter, hair-raiser, my blood-stone girl.

She is a cut asterism adorning an armour of hair.

When I loosen her pleats, a storm rises.

February gales batter our windows, Clyde squalls

tie ships to their harbours. The cinnamon falls

of her hair engulf me, follow me like notes

plucked from a guitar – each string vibrating

through the air songs from a girl's hair.

The girl is my ten-year-old daughter.

Daily I traverse her jungle; snakes

squirming between us. Growing for so long,

brushed, combed, the hair of my daughter

is her signature. The hair of my daughter

wraps her up in a hair parcel – all bows

and ribbons with the bite of a feral dog.

The hair of my daughter is her doppelganger -

her image caught in its many folds.

It knows the language of pony tails, braids,

bands and bobbles. Her hair has been dyed red,

dyed purple. Her hair hangs around her,

a thick veil coiling when it senses danger.

The hair of my daughter is as old

as the Hanging Gardens of Babylon,

mysterious as the riddle of the Sphinx

and the riddle is growing day by day.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Fizza Abbas: The Unburnt Toast

A pale, brown woman with unkempt tresses

walks along the pavement. The asphalt and concrete cracked with age:

A barren thoroughfare of desires - A road to hell in-the-making

Her black eyes look around

the remnants of a half-eaten apple look tempting.

She hides it secretly inside her cleavage -

A feeble attempt at a brutal revenge

Those once altruistic soldiers become mannequins.

My poor Pakistani mother in a slum

Too has feelings, too has rage.

They say have patience, you will get the aid you deserve.

Don't they know the toast has burnt and the jam is now wet?

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Bethany Rivers: Awaken

In a bombed-out street, wind moves the lips

of a politician on a poster. Ilya Kaminsky

This is not a bombed-out country

but the hospitals are suddenly

full of dying black women who

do not know a word of English.

They are older than Snowdonia, the

Pennines, Ben Lomond, Ben Nevis. Yet

they are as young as you or me.

The doctors can’t seem to diagnose

any sickness, yet their vitals are

fading fast. The papers are full

of the news, thousands of black

women who know that truth

is dying. They have given birth

to generations of Africans, Australians,

Americans, they know where blood

comes from. They don’t know what

a mobile phone is or any kind of computer,

yet they’re all connected, every one of them

loses another breath, another heartbeat,

at the exact same hour, across the land.

They breathe as one together. They die

as one together. The doctors don’t know

what to do. The papers are full of the news,

thousands of black women who know the truth

and don’t speak our native tongue, are dying.

Deep within, we know their ancient wisdom,

but we’ve forgotten it. Our only hope

is to dream their dying breath into us,

breathe their truth into our dreams,

awake with their language on our lips.

Bethany Rivers: Once upon a voice

It was a dark ink spot, dried many years ago, at the back in the far

corner of an old fashioned school desk. It looked black at first, but

upon closer inspection, it was navy blue, spreading like a

Rorschach blot to lighter shades. The desk was hidden in the wings of

the school stage, the school itself closed down decades ago.

snapped rulers

long corridors

to whistle down

I liked the smell of the desk, the squeak of its hinge as I opened it.

I liked the quiet rebellion of the ink, not finding the page to articulate

words, but to be quietly raucous, spoiling any books or papers that

may have been there. The ink learning to find its own shape.

kiss the grain of wood

sink in

deeper

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Nancy Mattson: Student Mobilization Order, Fire Prevention Unit

Hiroshima, 6 August 1945 [After photographs by Hiromi Tsuchida]

That we cannot find our children

And we trained them to prevent

That blackness fell in flakes

And the ashes were

That the world went silent

And our tongues

*

That I found Akio’s jacket hanging

And nothing else on the tree

That the badges I sewed on the arms

And the threads held

That I can hold his jacket, its torn shoulder

But not his body, my first-born son

*

That I found Yokisho’s water bottle, twisted

But not her body, my only daughter

*

That I found Reiko’s lunch box, intact

Her peas and rice uneaten, carbonized

*

That we are breathing into our lungs

Our children’s bodies, vaporized

*

That I found Akio’s jacket hanging

And nothing else on the tree

That the badges I sewed on the arms

And the threads held

That I can hold his jacket, its torn shoulder

But not his body, my first-born son

*

That I found Yokisho’s water bottle, twisted

But not her body, my only daughter

*

That I found Reiko’s lunch box, intact

Her peas and rice uneaten, carbonized

*

That we are breathing into our lungs

Our children’s bodies, vaporized

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Jane Kirwan: Mystery

His homework is to make a time-line of the crucifixion

– what is a time-line?

Grandparents must have taken him to church in Enugu,

have knelt with him before the altar.

Surely he noticed the silence once the heavy door shut

leaving the heat, red dust, crowds outside?

He can’t remember a priest or any incense

– maybe there was singing –

no memory of pictures: journey of a man to his death.

How to explain the Stations of the Cross?

He knows train stations in South London,

which ones to avoid

but how to keep him safe, this gentle boy?

How to explain the point

– the viciousness behind the group over there

or those there, throwing dice –

of religions: crown of thorns, nails driven in,

a crowd jeering, cheering the murderers on.

How to learn about suffering: shuffling from image

to image, slowing the breath, constricting the chest.

He’s eleven, lives with Roblox and Minecraft

and police tape, and gangs.

How to explain the rage, the blindness,

slide of a blade as it slices into the dying man’s side.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

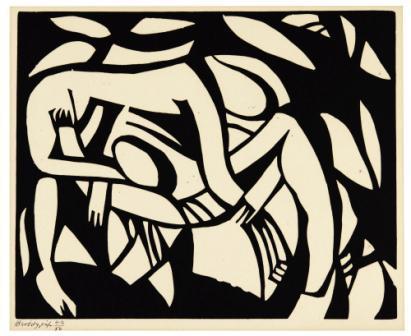

Julia Duke: The Wrestlers

inspired by 'Wrestlers' (linocut), Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, c. 1914

Intimacy hovers, poised at the point of a knife:

the artist's decision, skilful incision, will shape

the outcome of this skirmish. When a scuffle

breaks out among boys who knows

where it will end.

No easy brush strokes; each cut made with purpose.

Each thrust of the knife a new thrust

in their struggle. Each twist of the torso

a deep violation, a mute exhortation,

a tentative knowing.

Interwoven, interlocking, grasping and gasping,

panting and rasping, poised on the cusp

of success, almost basking,

then a plunging, sudden lunging,

interlinking, almost sinking.

Blood runs deep. It's thicker than water.

They grapple and tussle, inextricable tangle,

convolution of limbs, a contortion, a wrangle.

Caught up with each other in

the search for a brother.

Intimacy hovers, poised at the point of a knife:

the artist's decision, skilful incision, will shape

the outcome of this skirmish. When a scuffle

breaks out among boys who knows

where it will end.

No easy brush strokes; each cut made with purpose.

Each thrust of the knife a new thrust

in their struggle. Each twist of the torso

a deep violation, a mute exhortation,

a tentative knowing.

Interwoven, interlocking, grasping and gasping,

panting and rasping, poised on the cusp

of success, almost basking,

then a plunging, sudden lunging,

interlinking, almost sinking.

Blood runs deep. It's thicker than water.

They grapple and tussle, inextricable tangle,

convolution of limbs, a contortion, a wrangle.

Caught up with each other in

the search for a brother.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Phil Connolly: Granite Zachary

Rock ‘ard Zach to his mates.

He’s cock o’ the class by a chasm

and needs to be to put his fists up

and defend the honour

of his perfectly normal nose

against the lies of friends, so called,

whose baiting would persuade him,

from the wariness of distance:

Zach the hooter, Zach the conk,

yer sneck’s as long as an elephant’s trunk.

But chants are trance-inducing. Plus clear

numerical advantage makes them bold.

Lifting a shoulder towards their cheeks,

raising and dropping that arm, charging

towards him they’re doing the elephant –

charging towards him retreating

and charging they trumpet and scram,

trumpet and trumpet and scram.

Zachary collars each in turn, blackens

and cracks, fattens and thickens and smacks

an eye, a tooth, a lip a lug a gob until,

for want of breath, the action stalls.

Zach’s unmarked but smarts: betrayed.

The bloodied, battered and bruised

affect a grin. They might declare

the score a draw, if this were just a game.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Pascal Fallas: The Letting Go

I know you lie in the dark still moving

around the wild topography of school

and humiliation. Wind-blasted and sore

on some borderless moor of adolescence

with no fixed end, no moment where

you say: yes, now this is an adult’s

life. You know I also swallowed

those gruff years whole like adder eating vole.

Hurt from a quarter century back

sometimes cries like curlew here in the night

and echoes between our mirrored backs.

And you tell me without hesitation that curlews

don’t cry in the dark, but did I say that

out loud and is it really true?

Besides what I mean is not that

but instead: why are we still thigh-deep

in the cotton grass of forming personalities?

Why are we still perched on those high

youthful outcrops reliving errors

that freeze me now? Do you feel this too?

Are you also stopped by the danger and shameful

behaviour that lies and revives in the mind?

Do you know I have such thoughts that pull

with the density of a fell and land as ice-sharpened

rain which sheers across the landscape

to meet my face? You too have this owl-dish

opened to signals from the past: flattened

cheeks, broad bones, ears

expansive and locked onto distant noise

beaming, booming. You retain everything

and the children are out there now, roaming

through their own moorland of heather

and flooded streams, lonely abandoned

farms and sodden ground, collecting

and storing it all, wind-blind and ignorant.

Should they forget nothing too?

Perhaps after everything we are all

the same, here in the dark, fuller

than we know and moved to a halt.

We are stuck here lying, lying still.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Alison Campbell: Off sick from work

In bed, my daughter sleeps

away her illness. I sit reading

In the swivel chair by her table.

The noon sun falters; snow

is imminent. I turn the chair to catch

more light, turn a page over.

It’s like this time over –

we sit with children sleeping,

watching, waiting for them to catch

themselves. But unlike reading.

this quiet seems fragmentary, like snow –

soft, deep, never immutable.

My arms and head rest on the table.

We breathe in tandem. She curls over,

sighs. I pull the blind against the snow

dazzle and drift into a sleep

of sorts. (Tiredness has made reading

pall.) There’s a pull to try and catch

the essence of her being. I catch

my breath as she flails an arm. The table

creaks as I stir. The book she’s read

falls to the floor. The cat starts, jumps over

her foot. She doesn’t wake from the sleep

she needs; recuperative. It’s now

dimmer. Slight wind drifts the flakes of snow

against the pane. Does it bring dreams, or catch

you unawares – pull you into a deeper sleep?

The cat springs up, comfortable

on the bed again, kneading the quilt over

and over, till he nests down. I read

into this an acceptance, a readiness

to claim sleep as his right, too. Snow

falls faster, covers gardens. Day’s over.

The sun dips, just catching

the standing mirror, tilted, on the table;

a shiny dream-catcher reflecting sleep.

The snow soothes – it’s inevitable.

We catch the day, then it’s over.

Sleep comes – we’re more than ready.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Shikhandin: Snow From Your Cell Phone

You hold up the irregular pentagon

you scooped up from the sidewalk. You promise not to eat it.

The road swings as you walk. The path you take

to college, to your rooms. The store where you buy

sifted rye flour, and I

googled to find out if chapattis could be made

from it. Broccoli is cheap here, you say,

a satisfied smile lighting up your snow-kissed face.

Thank goodness they speak English here. But you’ve learnt

to say ‘tack’ and a few other words already. Neither

of us had seen snow before. So, you show

it to me again. Its edges melting into your mitten-warm

hand and off the screen. You wave and I see

the snow falling like possibilities

from the trees. You aim at the ground.

Your footprints on the talc-like surface,

so deliciously clean. And then up, towards cloud-bright

sky with a tatting of blue. European crows

gather – a murder of crows, right? – near

a snow dusted bench. A red truck slides forward. Your canvas.

A lock of your hair swings out of vision. My canvas.

Our brown irises eat picture-postcard beauty. Indian plum

is a February fruit. We offer it first to our Goddess

of learning, who rides a snow-white

swan. You have shown me snow, but I’ll never

show you my hidden snowstorm. The rink

of frozen tears where I skate

my anxieties away. My knees shake

like leaves. The fruit’s sharp sweetness nips

my tongue. I show you its white flesh

beneath smooth green skin. You pretend

to lick your ice-clod. You throw a balled-up challenge

at me before you go in

to your laboratory. Your world shuts its door. But

your voice lingers long after my cell phone

has turned darkly mute. I shut your room. It feels

so distant now, and cold. I hold the ball of yarn I’d meant

to crotchet into a scarf. A piece of lint wafts. A sunray

catches it. Softly. Like a footfall in the snow.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Robert Nisbet: Blue Stockings

She goes to London University in 1935

Phrases like depravity and lusts of the flesh

and abomination were mercifully absent

from the minister’s remarks, that summer evening

when the chapel marked her departure

and wished her well. He simply spoke

of a plethora of new experiences.

The envious called her Bluestocking. She read

for her BA in history, she talked of Marx

and Fox and Pankhurst, the still-suspect Darwin.

She bought blue stockings too, a lovely pair,

on one of her dawdles down Petticoat Lane.

One evening Michael laid embracing hands

on stocking and leg. Their breathing

was wet with wine, and the hint, the whiff,

of a hitherto unknown communion.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Rosemary Norman: Symphony Jane

There was a blackbird on the lawn

singled them out

the instant she was put into his arms

as any child might be,

and that’s a well-known omen

though of what, he saw

no consensus online. He named her

Symphony, for a life

long, complex and with various discords

eloquently placed. She

had mumps, measles and glue ear

and was Simmie at school.

She came downstairs with such sureness

he knew this was a tryst

not a date. She hugged him and was gone

to that young man

he must suppose has sable plumage

and eyes rimmed with gold.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Robin Houghton: Hazel is fascinated by space

When you kick that football to the edge of the lawn and ask

where should I put the tennis ball we talk about relative size

and distance and relative scale. There's no room for the sun

in this garden or even this town so we stick with planet Earth

and Moon. Out comes the tape measure just about here I say.

We contemplate the balls. The moon is bigger than I thought

but I'm loath to tell you this for fear of breaking your reverie

or letting on that the more you know the more ignorant you feel.

Instead I tell you about the mini-moon the size of a family car

just passing by when Earth pulled it in. No-one knows where

it's driving from or to, or quite how long it's been hitchhiking—

a dot of a thing, with pretentions—smooth arriviste spooling away

while the real Moon, blue moon, lovely moon of all our dreams

and nights hums its own song, looks to its shadow, assesses

the cesspit of its universe with all the satellites, abandoned bits

of craft, landing gear, sundry items dropped by astronauts,

the whole orbiting junkyard necklacing our planet just out of reach.

I want to tell you it wasn't always like this, it wasn't about us.

Meanwhile mini-moon, baby-moon, emergent with hope and pathos

on its egg-shaped path, is soon to be flung away, yet again.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Sarah James: Marcasite

The watch Nan gave me never worked

longer than a few months. The trick,

she reminded me, was to keep it wound,

but not over-wind it. Whatever colour

her wig, Nan’s curls were always sleek

and tight. She’d clutch my wrist, tell me

I was her favourite – her first, prized

eldest grandchild, though perhaps

she said likewise to my sister and cousins.

She smiled, toothy as a polished watch-cog,

even as she grew thinner and shorter,

even as she out-survived one daughter.

Her intricate silver-linked watch

hangs loosely on my wrist, unticking.

I finger the strap; each tiny marcasite

still shines as bright as her eyes did.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Ian C Smith: Inside a Room

Hopper glimpses through one of the many windows in this city, a man hunched

forward who reads. A woman sits, turned away from him, one finger on a piano’s

keys. His newspaper casts shadow on a round table separating them. Framed

pictures within this frame in the background blur like some memories. Between

viewer and foreground, unseen, lies Greenwich Village’s resting pulse, all that has

happened, shall happen. We see what might be a closed door, but no handle,

perhaps the bedroom. The night washes them in angled light. What scents pervade

this room? Does she pick out a favourite composer? Satie? Something elegiac, or

the strain, Santa Lucia, from the recent movie, A Farewell to Arms? A Mills Brothers

song? Has hearing her solitary notes become his habit?

. Now, here, her name kissed

gone dancing with ghosts of lust

body heat lingers.

. Now, here, her name kissed

gone dancing with ghosts of lust

body heat lingers.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Fraser Sutherland: The Scandinavian Detective

He wakes early, finding darkness in the dawn.

He hasn’t slept long or well. He makes himself a cup of tea,

a restful time before a restless day. For some years

his wife’s been absent, she couldn’t take the irregular hours

of a dedicated detective, the uniformity of his dourness.

He looks out a window on the street. It’s snowing, though

it will soon change to rain, hail, fog, or sleet. He hopes

his old car will start, but doesn’t expect it to. He’d get another

if he could afford it. His key doesn’t make it go. He’ll have to

walk to the squat grey building with one light burning,

his office waiting for him, desk strewn with uncompleted paperwork.

He pours the first of the many cups of the toxic coffee

in which the squad room specializes. They won’t get better.

As the hours pass he checks the office of a colleague

to see if he’s in. He isn’t. He never is.

Nor is his boss, the police chief, she’s on another floor,

making a statement to the press. Back at his desk

he reads again a daily thickening file about the bones,

the friendless bones he broods about awake or in fitful sleep.

Nobody knows where they came from, or how long

they’ve lain, caked with earth, in the unearthed hole.

He should go out to lunch but orders instead a sandwich.

Then he’ll have to tell his team to meet and hear of nothing new

but they’ll keep on doing what they have to do.

He’ll get answers eventually but won’t like them when he does.

He reads the file again, then puts it aside.

As he often does, he ponders getting a quiet place in the country,

the acquisition of a dog.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Phil Kirby: A Model Wife

How she becomes his masterpiece

with every stroke, each subtle daub

of blue or green on her bare arms,

beneath one eye, that shadowed flesh

almost concealed by rose-blush tints

applied to each cheek. Instructed

by him in every pose, she sits –

in a plain dress of his choosing,

hair styled and tied to his desire –

as he creates her public face:

the shallow smile and haunted look

that some critics will interpret

wrongly, calling it dispassion,

while remarking on the artist’s

skill in capturing her likeness,

her spirit, in two dimensions.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Stuart Henson: Every Breath You Take

A hit based on a misconception.

Well, people hear what they want to hear.

So now when fear stalks like a predator

greedy for TV’s lurid disconnects,

hot to emerge and shake our hands

like one of Juke Box Jury’s waiting bands

and words get twisted to the sinister

each time the experts turn their thumbs

it’s harder still to fill your lungs, to hum

along, like when some jumped-up minister

coughs out statistics from an autocue…

Yet all the while you know I’m watching you,

helpless, ear-wormed, undone by that song—

and its insistence that we read it wrong.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Emma Neale: Arrhythmia

The young physician

jogs the tree-canopied avenue

white earphones hutched

in his ears, old blue iPod clutched

in a fist that he holds a little aloft

as he presses the small metal song-box

against the air’s clammy ribs

his expression abstracted yet intent

as if he’s never not on shift:

with the smallest of stethoscopes

auscultates our era’s

serious irregularities.

Back to poet list…

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Fizza Abbas is a Freelance Content Writer based in Karachi, Pakistan. She is fond of poetry and music. Her works have been published on quite a few platforms including Poetry Village and Poetry Pacific.

Daniel Bennett was born in Shropshire and lives and works in London. His poems have been published in numerous places, including Wild Court, The Frogmore Papers and Poetry Birmingham. His first collection West South North, North South East was published in 2019.

Tony Beyer writes in Taranaki, New Zealand. He is the author of Anchor Stone (2017) and Friday Prayers (2019), both from Cold Hub Press. Recent work has appeared in Hamilton Stone Review, Landfall, Mudlark, NZ Poetry Shelf and Otoliths.

Zoe Brooks lives in Gloucestershire. She’s had poems recently published in Birmingham Poetry Journal, Ink, Sweat and Tears, Prole, and Fenland Reed. Her collection Owl Unbound will be published by Indigo Dreams in Autumn 2020. She is currently working on a collection about her time in the Czech Republic

Curtis Brown is a British, London-based creative who believes in the promiscuity of poetry. He uses various art forms to tell tales, and is excited by the fact that poetry inevitably permeates them all.

Molly Burnell is based in the Northamptonshire countryside, she’s intrigued by the beauty found in the ugly and vice versa, with special interest in anything and everything ecological. She’s appeared in several issues of The Dawntreader, the university anthology, Heritage, and soon to be featured in Sarasvati, as well as Slice of the Moon Books’ anthology, Earth, We Are Listening.

James Roderick Burns’ fourth short-form collection, Height of Arrows, is due from Duck Lake Books in 2020. His work has appeared in The Guardian, The North and The Scotsman. He lives in Edinburgh and serves as Deputy Registrar General for Scotland.

Alison Campbell, from Aberdeen, now lives in London. She is a teacher/counsellor with poems in publications, including Obsessed with Pipework, The Curlew, The Poetry Village, Dunlin ‘Port’ anthology and Reach. She was shortlisted for Segora Poetry Prize, 2018 and commended in the Barnet Poetry competition 2017, 2018. She has work forthcoming in Dawntreader and Sarasvati.

Phil Connolly is married and lives near York. He taught for many years in North Africa and the Middle East. He was shortlisted in the Wordsworth Trust Competition and has been published in several anthologies and magazines including The High Window, London Grip, The North and Dream Catcher.

Julia Duke is a nature writer and poet who has found her inspiration living in England, Wales and the Netherlands. She has written a regular literary column for the HagueOnLine and published poems in various magazines and anthologies, including Fifth Elephant (Newtown poets anthology) and the Suffolk Poetry Society magazine Twelve Rivers

Marie Dullaghan was born in Dublin. She is a retired education worker, fine arts photographer, musician, actor, writer and poet. A long-term member of both the Poeticians and Punch collectives in Dubai, she has performed regularly at events including the Emirates Airlines Festival of Literature. Has work has been published in The Shop, The High Window and elsewhere.

Pascal Fallas is a writer and (occasional) photographer currently living in Norfolk, UK. His poems have recently appeared in The Fenland Poetry Journal, Brittlestar and The Alchemy Spoon. For more information, or to make contact, please visit www.pascalfallas.com.

Mary Franklin’s poems have appeared in numerous print and online magazines and anthologies including Bonnie’s Crew, Ink Sweat and Tears, Iota, London Grip, Nine Muses Poetry, The Stare’s Nest and Three Drops from a Cauldron. She lives in Vancouver, British Columbia.

Leona Gom was born on a remote farm in northern Alberta, Canada. She has published six books of poetry and eight novels, and her work has won several awards and appeared in many anthologies and translations. Her novel The Y Chromosome has recently been reprinted by Cormorant Books

Stuart Henson’s most recent collection is The Way You Know It, New & Selected Poems (Shoestring 2018). A book of sonnets sent on postcards, in collaboration with John Greening, is due from Red Squirrel this November.

Robin Houghton’s most recent pamphlet Why? was a joint winner of the Live Canon Pamphlet Competition in 2019. Her poetry appears in many magazines including Agenda, Magma, Mslexia, Poetry News, The Frogmore Papers and The Rialto, and in numerous anthologies. Awards and competition successes include the Hamish Canham Prize and the Poetry Society Stanza Competition.

Jack Houston is Hackney Library’s poet in residence. His work has previously appeared in a few anthologies and Blackbox Manifold, The Butcher’s Dog, London Grip, Magma, Poetry London and Stand.

Sarah James/Leavesley is a prize-winning poet, fiction writer, journalist and photographer. Her most recent project is > Room, an Arts Council England funded multimedia hypertext poetry narrative. Collections include How to Grow Matches (Against The Grain Poetry Press, 2018) and plenty-fish (Nine Arches Press, 2015), both shortlisted in the International Rubery Book Award. Her website is at http://sarah-james.co.uk

Jennifer Johnson was born in the Sudan and has worked as a VSO agriculturalist in Zambia and later as an editorial assistant. She has a pamphlet Footprints on Africa and Beyond (Hearing Eye, 2006) and a book Hints and Shadows (Nettle Press, 2017).

Peter Kenny writes poems, plays, short stories and, as Skelton Yawngrave, adventures for children. His poetry includes The Nightwork (Telltale Press 2014) and A Guernsey Double (2010, Guernsey Arts Commission) a new pamphlet Sin Cycle, is due this year. Find him at peterkenny.co.uk

Lancashirep-born Angela Kirby now lives in London but has also lived in France and spent much time in Spain and the US. Her poems are widely published, have been read on Radio Four and TV, and have appeared On the Busses. She gives frequent readings in the UK, Europe and the US. Her 5th collection, Look Left, Look Right … came out in April 2019.

Phil Kirby’s collections are Watermarks and The Third History. Poems since in Poetry Ireland and others. A teen novella, Hidden Depths, is available on the Kindle platform. He has been organising ‘Writers at The Goods Shed’ in Tetbury

.Jane Kirwan’s latest poetry collection was published in 2019 by Blue Door Press. The poems move between a village in Central Bohemia and one of a similar size in the West of Ireland, between a Goose Woman and a grandmother

Marion McCready lives in Dunoon, Argyll. She is the author of two poetry collections – Tree Language (Eyewear Publishing, 2014) and Madame Ecosse (2017).

Jane McLaughlin’s poetry has appeared in many magazines and anthologies (including London Grip). and The New European. She has received awards and commendations in national competitions including the National Poetry Competition long list, Hippocrates Open, Torriano, and Torbay competitions. Her collection is published by Cinnamon Press. She also writes and publishes short stories.

Kathleen McPhilemy grew up in Belfast but now lives in Oxford. She has published three collections of poetry, the most recent being The Lion in the Forest (Katabasis, 2005).

Nancy Mattson’s fourth full collection is Vision on Platform 2 (Shoestring 2018). She contributed the title poem for Her Other Language, an anthology of Northern Irish women’s writings on domestic violence, ed. Ruth Carr & Natasha Cuddington, (Arlen House 2020).

Emma Neale is a writer and editor based in New Zealand, who has had 6 collections of poetry and 6 novels published. She has a collection of short stories due out later this year. This year she received the Lauris Edmond Memorial Award for a Distinguished Contribution to New Zealand Poetry. She is the current editor of Landfall

Robert Nisbet is a Welsh poet and sometime creative writing tutor at Trinity College, Carmarthen. He has published widely and in roughly equal measures in Britain and the USA. He is a Pushcart Prize nominee for 2020.

Rosemary Norman lives in London and has worked mainly as a librarian. One poem, Lullaby, is much anthologised and her third collection, For example, was published by Shoestring Press in 2016. Since 1995 she has collaborated with video artist Stuart Pound. Her poems become soundtrack, image, and sometimes both, and she has performed live with film. The work has been screened regularly at film and video festivals, and is on Vimeo

Moya Pacey was born and grew up in Middlesbrough in what was then Yorkshire. She now lives in Canberra, Australia. She published her second collection: Black Tulips (Recent Work Press, University of Canberra) in October, 2017. She co-edits the on-line journal, Not Very Quiet notveryquiet.com. Her next collection will be published by Recent Work Press in 2020.

Tom Phillips lives and works in Sofia, Bulgaria. His poetry has been published in a wide range of journals, anthologies, pamphlets and the collections Unknown Translations (Scalino, 2016), Recreation Ground (2012) and Burning Omaha (2003). His plays have been produced by theatres in Bristol and Bath and he currently teaches creative writing and translates contemporary Bulgarian poetry.

Colin Pink’s poems have appeared in various magazines such as Poetry Ireland Review, Acumen, South Bank Poetry, Magma, Under the Radar and Poetry News. He has published two collections: Acrobats of Sound, 2016 from Poetry Salzburg Press and The Ventriloquist Dummy’s Lament, 2019 from Against the Grain Press.

Bethany Rivers has two poetry pamphlets: Off the wall, from Indigo Dreams; the sea refuses no river, from Fly on the Wall Press. Author of Fountain of Creativity: Ways to nourish your writing from Victorina Press. She is editor of the online poetry magazine As Above So Below. She mentors writers from the start of their projects through to publication.

Mary Robinson’s poetry publications include Trace (Oversteps 2020), Alphabet Poems (Mariscat 2019) and The Art of Gardening (Flambard 2010). A poetry/photography collaboration Out of Time was exhibited in 2015. She lives in North Wales. www.poetrypf.co.uk/maryrobinsonpage.shtml

Indian writer Shikhandin has been published worldwide. She has won awards in India and abroad. Books include Immoderate Men (Speaking Tiger) and Vibhuti Cat (Duckbill-Penguin-RHI). Amazon:https://www.amazon.com/Shikhandin/e/B07DHQM6H5/ref=sr_tc_2_0?qid=1533117978&sr=1-2-ent Face Book: https://www.facebook.com/AuthorShikhandin/

Ian C Smith’s work has appeared in, Amsterdam Quarterly, Antipodes, cordite, Poetry New Zealand, Poetry Salzburg Review, Southerly, & Two-Thirds North. His seventh book is wonder sadness madness joy, Ginninderra (Port Adelaide). He writes in the Gippsland Lakes area of Victoria, and on Flinders Island, Tasmania.

Fraser Sutherland is a poet, editor, and lexicographer. He lives in Toronto.

Tanner was shortlisted for the Erbacce 2020 Poetry Prize. His latest collection Shop Talk: Poems for Shop Workers is published by Penniless Press

Ruth Valentine is a writer & an activist for migrant & refugee rights. Her latest publications are Rubaiyat for the Martyrs of Two Wars and A Grenfell Alphabet. She lives in Tottenham

Aug 31 2020

London Grip New Poetry – Autumn 2020

*

The Autumn 2020 issue of London Grip New Poetry features:

*Zoe Brooks *Colin Pink *Tony Beyer *Leona Gom *Daniel Bennett *James Roderick Burns

*Jack Houston *Tom Phillips *Moya Pacey *Mary Franklin *Curtis Brown *Peter Kenny

*Angela Kirby *Kathleen McPhilemy *Ruth Valentine *Marie Dullaghan *Molly Burnell *Tanner

*Jane McLaughlin *Jennifer Johnson *Mary Robinson *Marion McCready *Fizza Abbas

*Bethany Rivers *Nancy Mattson *Jane Kirwan *Julia Duke *Phil Connolly *Pascal Fallas

*Alison Campbell *Shikhandin *Robert Nisbet *Rosemary Norman *Robin Houghton

*Sarah James *Ian C Smith *Fraser Sutherland *Phil Kirby *Stuart Henson *Emma Neale

Copyright of all poems remains with the contributors. Biographical notes on contributors can be found here

London Grip New Poetry appears early in March, June, September & December

A printer-friendly version of this issue can be found at

LG New Poetry Autumn 2020

SUBMISSIONS: please send up to THREE poems plus a brief bio to poetry@londongrip.co.uk

Poems should be in a SINGLE Word attachment or else included in the message body

Our submission windows are: December-January, March-April, June-July & September-October

Editor’s notes

Michael Bartholomew-Biggs

London Grip poetry editor

Forward to first poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Zoe Brooks: Perhaps That Easter there were angels everywhere, electric in the air, a frisson of freedom, a lamentation of song. Perhaps it was the poet president racing through marble halls on a child's tricycle, arriving at meetings with a squeak and a crash; perhaps it was that cold spring wreathing the statues with garlands of mist, a spring that had been so long coming, arriving only with a jingle of keys; perhaps it was the candles guttering in Wenceslas Square, tears bejewelling the flowers with ice, the women bowing before the black and white photograph, that made us believe that this time history would not repeat its cruelties, that Prague's angels would not prove to have leaden wings. And there I was, so obviously alien that I walked in the middle of the pavement, without looking over my shoulder. In the warm light of Cafe Slavia, drunk on long black coffee, I asked about the future. And the answer was always the same – “Perhaps.”Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Colin Pink: The Problems of Philosophy after Bertrand Russell The table I write at appears solid, smooth and polished; reflections of light glow white on its surface. If I turn my head the colours change, the highlights skate across the top; one edge looks longer but isn’t. Depending on your point of view it all looks different. To the painter these things are important. Russell’s elegant prose claims we always experience a veil of appearances, never reality; and to make it sound scientific he calls it ‘sense data’. That world seems to be reliable, dependably the same, tomorrow as it was today. And yet, we’re like chickens who everyday are fed by the farmer at the same time. But one day instead of feeding the chickens he wrings their necks. This is known as the problem of induction. And not a lot of chickens know that. And neither did I. Colin Pink: Never Accept Words from Strangers Did you pack these words yourself? Has anyone given you words to carry for them? Have you left your vocabulary unattended at any point in your journey? As they snap on the rubber gloves to probe, persuade and intimidate you realise you’re costive with words that aren’t yours. Don’t accept words from strangers however well-meaning they appear. Remember: Cui bono? Cui bono? Remove their hand from your crotch/purse/mouth; rip out their fake smiles with your teeth. There’s violence folded within everyday phrases: Take Back Control, Economic Migrants, Make [INSERT NATION HERE] Great Again.Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Daniel Bennett: The Panda The sounds of the house begin above him, a family waking. He thinks of Stalin preferring a sofa to a presidential bed, of the ace of pentacles gleaming from the apocrypha of a bookshelf of the bottle of Cahors he drank last night, a black wine, dark as a tarot reader's smile. He winds the blanket tighter, but sleep has vanished for another day. Stalin lay dead for days because lackeys wouldn't wake him. Lucky Stalin. He considers how all things are rare and fleeting: power, ambition, sleep, the ephemera that crams inside a head, even the emptiness that ensues when loves disappears. Already, this day is spoiled. Through the glass door of the lounge, his daughter watches. For how long he can't tell. Her gaze moves from the space he occupies, back upstairs, towards his former habitat. A radio sounds, a song about hips meeting, kisses, the rest. He lifts himself with the blanket wrapped about him, smiles and waves, because captivity should be safe for all. The girl retreats. He sees his reflection in the shine on glass: his pot belly, eyes dark from sleep. New footsteps press on the stairs, subtle and hesitant. He begins to dance across the cage, his claws scraping on squeaking boards, his tongue probing a shred of green bamboo.Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.