Poetry review – NO FAR SHORE: Norbert Hirschhorn enjoys Anne-Marie Fyfe’s travel memoir that weaves a course between prose and poetry

No Far Shore. Charting Unknown Waters

Anne-Marie Fyfe

Seren

ISBN: 9-781781-725177

132 pages £9.99

No Far Shore. Charting Unknown Waters

Anne-Marie Fyfe

Seren

ISBN: 9-781781-725177

132 pages £9.99

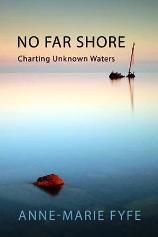

The front cover startles, a vision of a poem before even opening the book. A photograph showing a flat, calm sea, the sky pink-dimmed at twilight. In the foreground, a huge rock on which ships might founder unawares when the tide rises. Many yards off there is a wreck: the cargo ship Kaffir, a coal-fired, single-masted vessel, one of the class of Clyde Puffers that plied the western coast of Scotland hauling supplies, mail and a passenger or two. It sank in February 1974. The photo evokes an ethereal beauty, a calm belying storm and tragedy. But look further: notice a barely discernible ‘line’ between sea and sky, one almost within reach. That line, the horizon, is a fantasy, as Fyfe’s poetry will teach us.

Thus, we enter No Far Shore. Charting Unknown Waters, Anne-Marie Fyfe’s omnium gatherum paean to coastlines, the sea, horizons, maps, the people; a memoir of growing up on the margins of Antrim, Northern Ireland, looking across the bay to Scotland at the Irish Sea’s narrowest point, the Straits of Moyle. The book is about ancestors, and about contingencies that led to her own origin. Fyfe’s grandfather, William Reilly, was a ship fitter who helped build the Titanic, a Protestant (such jobs weren’t given to Catholics), but because he eloped with Mary McNeill, a Catholic, he was not taken aboard that fateful maiden voyage.

Fyfe summarizes the intent of the book: “Like the coast waters it sets out to explore, this book takes no settled form. It hovers on edges, on shifting shorelines. It weaves a course between prose and poetry. It dips in and out of both, steps continually off the dry land of travel writing, diary extracts, and observation…. as is always the case with poetry, continually changing margins.” Indeed, some of the poems take the shape of a ragged coastline, right-justified:

VANISHING POINT

Earlier today my horizons disappeared.

No trace of lines between sky & sea.

No joins, no delineations, between earth & the heavens.

I steady my gaze on a point

where the line ought to be

Here, a clouded-over sky hides the horizon, a line in any case constructed only in our minds because we’re not high enough to see the curvature of the earth. New England women looking out from their cupolas for the whaling ships’ sails to rise out of the sea knew this. (Not for nothing were those lookouts called ‘widows’ walks’.)

Robert Frost in his poem, ‘Neither Out Far Nor In Deep’, marveled that instead of looking at houses and active life, “The people along the sand/ All turn and look one way./ They turn their back on the land./ They look at the sea all day.” Fyfe wonders, “Perhaps it is only the horizon that has us hypnotized with the urge to contemplate our one quotidian hint of the infinite.” That infinite is a chilling prospect. It is the meaning of the one-syllable declarative word in the title: NO. There is no ‘far shore’ of redemption, afterlife, heaven. One of Fyfe’s fine poems, reproduced from an earlier collection (‘Late Crossing’) describes the poet’s journey to oblivion, starting out from a metaphorical family home, rowing to the horizon, acting her own Charon.

NO FAR SHORE

It will be winter when I untie

the boat for the last time:

when I double-lock the back door

on an empty house,

go barefoot through bramble

& briar, measure each

Stone step to the slipway.

It will be night-time when I row

to the horizon,

steady in North-star light

the darkened house at my back.

It will be winter when I draw

each oar from the water,

shiver,

& bite the cold from my lip

(I can’t resist pointing out the prosodically apt hard ‘b’s and ‘c’s)

Fyfe is firm on this: Death comes without afterlife. Recall Tennyson’s ‘Crossing the Bar’, where the traveler sets out from a similar ocean shore but will meet his ‘Pilot face to face.’ But one must find that place, writes Fyfe, “Where we can gaze on a distant horizon that we know is imaginary anyway, a geometric and geographical construct, an optical illusion, and recognize that we are, some of us, endlessly, and not discontentedly, all at sea, with no promise of, no need for, the solace of a far shore.” An agnostic if not atheistic vision of destiny. Nonetheless, Fyfe testifies to power of belief in her poem, ‘Canticle: Star of the Sea’ (Stella Maris, an ancient title for the Virgin Mary). The priest recites a litany of waves: epic, doomed, ice-laden, etc., followed by the people’s response, “Pray for us,” closing with the Hail Mary, “Pray for us, now & at the hour of our death.” How can one not bow to the majesty of the sea?

Elizabeth Bishop ¬— the Nova Scotian Bishop — is the presiding spirit over the book. Her community of Great Village is so much like Fyfe’s Antrim, down to similar ESSO station pumps. Bishop visited Antrim in the 1930s. Fyfe stayed in Bishop’s house, her bedroom, looking up at the stars through the skylight. Both contemplated “missing mothers.” Both poets were sensible to rain, clouds, stripped thorn trees, deserted houses, bleak gull sounds, variations in light, remoteness and solitude. Aloneness. The word island cognate with isolation.

Other spirits visit whose lives overlap Fyfe’s, present or past: Robinson Jeffers, Virginia Woolf, Robert Louis Stevenson’s grandfather who built lighthouses Fyfe knows well. Guglielmo Marconi, inventor of long-distance radio transmission that allowed the radio telegraphers on the Titanic to tap out Morse code, -.-. –. – -.. (CQD, ‘all stations: distress’), then … — … (SOS), bringing nearby ships to the rescue of passengers in lifeboats. Fyfe incorporates Morse code into a final, long poem of memory, ‘Night Music’, to read, “No Far Shore.” She also includes a musical notation for violin, viola and cello the melody played by the band on the Titanic as that great ship went down, ‘Nearer My God to Thee.’ A plangent version should be heard: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gWIiwSKLQrc. Not only icebergs on the wide Atlantic, Fyfe also contemplates what is seen from her house on the coast: “This solemn home has witnessed/ too many shipwrecks, too few survivors./ The whole house heaves in early hours.” (“North House”).

The ‘Unknown Waters’ Fyfe charts with her poetry and reminiscences are longings for family, homes, and especially the coasts and islands she grew up near and explores again. An ancestor left Ireland for America but to find a home where, “the kitchen door opens/ & voices rise

what took you so long/, we’ve been here all day.

No Far Shore — rich in islands, shores, horizons, history, and reminiscences — may be savoured several times over.

.

Norbert Hirschhorn

Jul 20 2020

London Grip Poetry Review – Anne-Marie Fyfe

Poetry review – NO FAR SHORE: Norbert Hirschhorn enjoys Anne-Marie Fyfe’s travel memoir that weaves a course between prose and poetry

The front cover startles, a vision of a poem before even opening the book. A photograph showing a flat, calm sea, the sky pink-dimmed at twilight. In the foreground, a huge rock on which ships might founder unawares when the tide rises. Many yards off there is a wreck: the cargo ship Kaffir, a coal-fired, single-masted vessel, one of the class of Clyde Puffers that plied the western coast of Scotland hauling supplies, mail and a passenger or two. It sank in February 1974. The photo evokes an ethereal beauty, a calm belying storm and tragedy. But look further: notice a barely discernible ‘line’ between sea and sky, one almost within reach. That line, the horizon, is a fantasy, as Fyfe’s poetry will teach us.

Thus, we enter No Far Shore. Charting Unknown Waters, Anne-Marie Fyfe’s omnium gatherum paean to coastlines, the sea, horizons, maps, the people; a memoir of growing up on the margins of Antrim, Northern Ireland, looking across the bay to Scotland at the Irish Sea’s narrowest point, the Straits of Moyle. The book is about ancestors, and about contingencies that led to her own origin. Fyfe’s grandfather, William Reilly, was a ship fitter who helped build the Titanic, a Protestant (such jobs weren’t given to Catholics), but because he eloped with Mary McNeill, a Catholic, he was not taken aboard that fateful maiden voyage.

Fyfe summarizes the intent of the book: “Like the coast waters it sets out to explore, this book takes no settled form. It hovers on edges, on shifting shorelines. It weaves a course between prose and poetry. It dips in and out of both, steps continually off the dry land of travel writing, diary extracts, and observation…. as is always the case with poetry, continually changing margins.” Indeed, some of the poems take the shape of a ragged coastline, right-justified:

Here, a clouded-over sky hides the horizon, a line in any case constructed only in our minds because we’re not high enough to see the curvature of the earth. New England women looking out from their cupolas for the whaling ships’ sails to rise out of the sea knew this. (Not for nothing were those lookouts called ‘widows’ walks’.)

Robert Frost in his poem, ‘Neither Out Far Nor In Deep’, marveled that instead of looking at houses and active life, “The people along the sand/ All turn and look one way./ They turn their back on the land./ They look at the sea all day.” Fyfe wonders, “Perhaps it is only the horizon that has us hypnotized with the urge to contemplate our one quotidian hint of the infinite.” That infinite is a chilling prospect. It is the meaning of the one-syllable declarative word in the title: NO. There is no ‘far shore’ of redemption, afterlife, heaven. One of Fyfe’s fine poems, reproduced from an earlier collection (‘Late Crossing’) describes the poet’s journey to oblivion, starting out from a metaphorical family home, rowing to the horizon, acting her own Charon.

(I can’t resist pointing out the prosodically apt hard ‘b’s and ‘c’s)

Fyfe is firm on this: Death comes without afterlife. Recall Tennyson’s ‘Crossing the Bar’, where the traveler sets out from a similar ocean shore but will meet his ‘Pilot face to face.’ But one must find that place, writes Fyfe, “Where we can gaze on a distant horizon that we know is imaginary anyway, a geometric and geographical construct, an optical illusion, and recognize that we are, some of us, endlessly, and not discontentedly, all at sea, with no promise of, no need for, the solace of a far shore.” An agnostic if not atheistic vision of destiny. Nonetheless, Fyfe testifies to power of belief in her poem, ‘Canticle: Star of the Sea’ (Stella Maris, an ancient title for the Virgin Mary). The priest recites a litany of waves: epic, doomed, ice-laden, etc., followed by the people’s response, “Pray for us,” closing with the Hail Mary, “Pray for us, now & at the hour of our death.” How can one not bow to the majesty of the sea?

Elizabeth Bishop ¬— the Nova Scotian Bishop — is the presiding spirit over the book. Her community of Great Village is so much like Fyfe’s Antrim, down to similar ESSO station pumps. Bishop visited Antrim in the 1930s. Fyfe stayed in Bishop’s house, her bedroom, looking up at the stars through the skylight. Both contemplated “missing mothers.” Both poets were sensible to rain, clouds, stripped thorn trees, deserted houses, bleak gull sounds, variations in light, remoteness and solitude. Aloneness. The word island cognate with isolation.

Other spirits visit whose lives overlap Fyfe’s, present or past: Robinson Jeffers, Virginia Woolf, Robert Louis Stevenson’s grandfather who built lighthouses Fyfe knows well. Guglielmo Marconi, inventor of long-distance radio transmission that allowed the radio telegraphers on the Titanic to tap out Morse code, -.-. –. – -.. (CQD, ‘all stations: distress’), then … — … (SOS), bringing nearby ships to the rescue of passengers in lifeboats. Fyfe incorporates Morse code into a final, long poem of memory, ‘Night Music’, to read, “No Far Shore.” She also includes a musical notation for violin, viola and cello the melody played by the band on the Titanic as that great ship went down, ‘Nearer My God to Thee.’ A plangent version should be heard: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gWIiwSKLQrc. Not only icebergs on the wide Atlantic, Fyfe also contemplates what is seen from her house on the coast: “This solemn home has witnessed/ too many shipwrecks, too few survivors./ The whole house heaves in early hours.” (“North House”).

The ‘Unknown Waters’ Fyfe charts with her poetry and reminiscences are longings for family, homes, and especially the coasts and islands she grew up near and explores again. An ancestor left Ireland for America but to find a home where, “the kitchen door opens/ & voices rise

No Far Shore — rich in islands, shores, horizons, history, and reminiscences — may be savoured several times over.

.

Norbert Hirschhorn