Emma Storr is drawn into Gareth Writer-Davies’s poetic reflections on mortality

The End

Gareth Writer-Davies

Arenig Press

ISBN 9781999849146

£5.99 pp.36

The End

Gareth Writer-Davies

Arenig Press

ISBN 9781999849146

£5.99 pp.36

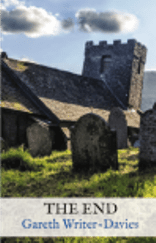

Both the title and the photograph of a graveyard on the cover leave us in no doubt about the subject matter of this pamphlet. The poems are written in the first person and although it is unfashionable to confuse the author with the speaker, I fear that Writer-Davies is exploring his own mortality after a diagnosis of cancer. We are kept in the dark about his chances of survival or any treatment offered besides surgery. That is irrelevant because the meat of the poetry addresses universal themes surrounding death: fear, anger, resignation and what, if anything, we leave behind. The topic may be morbid, but the poems are accessible and sparse, with plenty of humour and wry observations. They are never self-pitying and his economy of language, spacing and short lines hit home with poignancy and insight.

The poems appear to be written chronologically. The pamphlet opens with the poet waiting for his diagnosis in ‘Christmas Lights’. He tells God ‘I will try to be good’ so that He doesn’t send death ‘in his fat red suit’. The conflation of God with Santa works at many levels, humorous and ominous, particularly as crowds gather ‘on the memorial green’ to watch the festival lights being switched on. This is not the only poem in which prayer is invoked to plea for more time, a miracle or a cure. In ‘Fixed Price Service’ the poet addresses God directly and asks for a deal to prolong his life in return for fidelity and religious observance. It is a last ditch attempt, highly ironic and touching:

Lovely God. You have a wonderful spirit (you do) and my faith

in you is implicit; no reason

to doubt my sincerity, despite our previous relation.

Mortality concentrates the mind and can heighten everyday experience. Writer-Davies wonders what will remain of him once he has gone. I particularly liked the cynicism and wit of ‘Dead Poets’ in which he pokes fun at a trinity of editors, poets and doctors. The poem starts ‘editors / disapprove of poets’ and compares them with doctors dreaming of a hospital without patients. Both editors and doctors resent the people they are serving and:

like cadavers

poets are easier to edit

dead

and glamoured by their decease

may

even increase their readers (from a few to not very many)

The lack of punctuation, lower case type and use of occasional brackets are typical of Writer-Davies’ succinct style. He uses a few words to say a great deal. The white space between the stanzas slows down the reading so we linger on the images and stark single words. ‘Dead Poets’ ends with an invitation to editors:

here is a knife

now go about your business.

Although many of the poems are about the challenge to accept that death is inevitable and closer than desired, a few suggest hope in images and metaphors from the natural world. In ‘Bird’, where the speaker is on the operating table, numbed with drugs, ‘uncertain / of the next wing-beat’, he speaks of an instinct to retrieve:

enough

decay

to turn tears into sanguine flights of hope

It is unclear whether hope springs from removal of the decayed, diseased parts of the body or if these lines reference a metaphysical state. One of the four cardinal humours of the body is sanguinity, meaning optimism and positivity, as well as more literally ‘of blood’. In ‘Ash’, instead of scattering his ashes of five pounds and three ounces onto the river Teifi, the narrator wants his remains to be buried in the roots of an old ash tree that produces ‘a prodigious canopy of three hundredweight’ each year. Imperial measures sound heavier than metric weights to my ear and more impressive. Nourishing a tree with human remains recalls many myths and fairy stories, as well as suggesting that life will continue and flourish in the tree each Spring.

Serious disease often requires a shift in perspective about self-image and the reliability of the body. We see this reflected in the poems where the speaker mentions his transformation from a robust man to someone who is weaker, passive and alert to the Grim Reaper arriving at any time. ‘I am not / who I was’ (‘Tree’). In ‘Dust’ he describes how he used to clean and hoover regularly but now ‘I sit in my favourite chair / gathering’. Clearly, he will be dust himself soon.

Writer-Davies is particularly good at describing the boredom and apathy of illness. In ‘Torpor’ he bemoans the fact that he does not have the energy to write like Proust or to be inspired by Apollo, god of medicine and poetry. He concludes:

I will have done

nothing

to mend the cosmos

but

I was a great reader

The pathos and regret is lightened by Writer-Davies’ wit and sardonic approach to mortality.

The lack of control when facing serious disease is evident in ‘Twisting the Sheet’, a metaphor for the anguish the writer is experiencing, not comforted by the fact that he might have died of heart disease instead. As he comments:

nobody knows which bed Death

hides under

waiting

for a small death unnoticed

However, snatched time is precious and in ‘That Summer’, despite the diagnosis and his deathly appearance in the previous winter, the speaker is still alive:

……like brandy in a bottle

& having expected to be dead

I poured a large one instead

that summer

there were vitamins and sin; the sun was a furnace

The penultimate stanza is like a nursery rhyme and adds to the celebratory nature of the poem. The assonance of vitamins and sin is pleasing. The unusual combination of good and evil in this image is very satisfying. We want the speaker to enjoy sinning in the summer heat, the image of a furnace being reminiscent of the fires of Hell.

I hope I am wrong in my interpretation that Writer-Davies might have a life threatening condition. I look forward to reading more of his writing in the future and savouring the humour, humanity and intelligence he brings to his work.

Nov 14 2019

London Grip Poetry Review – Gareth Writer-Davies

Emma Storr is drawn into Gareth Writer-Davies’s poetic reflections on mortality

Both the title and the photograph of a graveyard on the cover leave us in no doubt about the subject matter of this pamphlet. The poems are written in the first person and although it is unfashionable to confuse the author with the speaker, I fear that Writer-Davies is exploring his own mortality after a diagnosis of cancer. We are kept in the dark about his chances of survival or any treatment offered besides surgery. That is irrelevant because the meat of the poetry addresses universal themes surrounding death: fear, anger, resignation and what, if anything, we leave behind. The topic may be morbid, but the poems are accessible and sparse, with plenty of humour and wry observations. They are never self-pitying and his economy of language, spacing and short lines hit home with poignancy and insight.

The poems appear to be written chronologically. The pamphlet opens with the poet waiting for his diagnosis in ‘Christmas Lights’. He tells God ‘I will try to be good’ so that He doesn’t send death ‘in his fat red suit’. The conflation of God with Santa works at many levels, humorous and ominous, particularly as crowds gather ‘on the memorial green’ to watch the festival lights being switched on. This is not the only poem in which prayer is invoked to plea for more time, a miracle or a cure. In ‘Fixed Price Service’ the poet addresses God directly and asks for a deal to prolong his life in return for fidelity and religious observance. It is a last ditch attempt, highly ironic and touching:

Mortality concentrates the mind and can heighten everyday experience. Writer-Davies wonders what will remain of him once he has gone. I particularly liked the cynicism and wit of ‘Dead Poets’ in which he pokes fun at a trinity of editors, poets and doctors. The poem starts ‘editors / disapprove of poets’ and compares them with doctors dreaming of a hospital without patients. Both editors and doctors resent the people they are serving and:

The lack of punctuation, lower case type and use of occasional brackets are typical of Writer-Davies’ succinct style. He uses a few words to say a great deal. The white space between the stanzas slows down the reading so we linger on the images and stark single words. ‘Dead Poets’ ends with an invitation to editors:

Although many of the poems are about the challenge to accept that death is inevitable and closer than desired, a few suggest hope in images and metaphors from the natural world. In ‘Bird’, where the speaker is on the operating table, numbed with drugs, ‘uncertain / of the next wing-beat’, he speaks of an instinct to retrieve:

It is unclear whether hope springs from removal of the decayed, diseased parts of the body or if these lines reference a metaphysical state. One of the four cardinal humours of the body is sanguinity, meaning optimism and positivity, as well as more literally ‘of blood’. In ‘Ash’, instead of scattering his ashes of five pounds and three ounces onto the river Teifi, the narrator wants his remains to be buried in the roots of an old ash tree that produces ‘a prodigious canopy of three hundredweight’ each year. Imperial measures sound heavier than metric weights to my ear and more impressive. Nourishing a tree with human remains recalls many myths and fairy stories, as well as suggesting that life will continue and flourish in the tree each Spring.

Serious disease often requires a shift in perspective about self-image and the reliability of the body. We see this reflected in the poems where the speaker mentions his transformation from a robust man to someone who is weaker, passive and alert to the Grim Reaper arriving at any time. ‘I am not / who I was’ (‘Tree’). In ‘Dust’ he describes how he used to clean and hoover regularly but now ‘I sit in my favourite chair / gathering’. Clearly, he will be dust himself soon.

Writer-Davies is particularly good at describing the boredom and apathy of illness. In ‘Torpor’ he bemoans the fact that he does not have the energy to write like Proust or to be inspired by Apollo, god of medicine and poetry. He concludes:

The pathos and regret is lightened by Writer-Davies’ wit and sardonic approach to mortality.

The lack of control when facing serious disease is evident in ‘Twisting the Sheet’, a metaphor for the anguish the writer is experiencing, not comforted by the fact that he might have died of heart disease instead. As he comments:

However, snatched time is precious and in ‘That Summer’, despite the diagnosis and his deathly appearance in the previous winter, the speaker is still alive:

The penultimate stanza is like a nursery rhyme and adds to the celebratory nature of the poem. The assonance of vitamins and sin is pleasing. The unusual combination of good and evil in this image is very satisfying. We want the speaker to enjoy sinning in the summer heat, the image of a furnace being reminiscent of the fires of Hell.

I hope I am wrong in my interpretation that Writer-Davies might have a life threatening condition. I look forward to reading more of his writing in the future and savouring the humour, humanity and intelligence he brings to his work.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2019 2 • Tags: books, Emma Storr, poetry