James Roderick Burns is moved by a thoughtfully chosen selection of Joan Ure’s defiant poetry

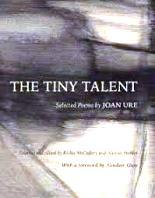

The Tiny Talent: Selected Poems

Joan Ure

( selected and edited by Richie McCaffery & Alistair Peebles.)

Brae Editions, 2018

ISBN 978-1-907508-07-3

£7.99

The Tiny Talent: Selected Poems

Joan Ure

( selected and edited by Richie McCaffery & Alistair Peebles.)

Brae Editions, 2018

ISBN 978-1-907508-07-3

£7.99

Reading The Tiny Talent is both a bracing and a saddening experience. Bracing for its content – acerbic, culturally-engaged, defiant verse that seems to have come from the darkest of places determined to bring light; saddening in that at 22 poems, barring any additional selections, it feels more like a poet consolidating beginnings than drawing things to a close.

One of the editors of the volume, Richie McCaffery, has written an excellent biographical and critical sketch about the woman who took on the world as Joan Ure (https://www.scottishpoetrylibrary.org.uk/poet/joan-ure/ – incidentally a site as good as the Scottish Poetry Library itself). It charts the life and literary development of Elizabeth Carswell (Elizabeth Clark after her marriage) from grim, strangled family beginnings (“Ure’s grandfather, a foreman, often spent an evening seated alone in the best parlour of his house, consuming a bottle of whisky in perfectly orderly silence”) through forced obedience to social norms, a partial break-out through drama and poetry – the two often fusing in The Tiny Talent within monologues and other forms brimming with performative energy – and the adoption of a protective nom-de-plume, to a unique voice combining ‘poetic’ lyricism with hard-bitten determination for change.

Ure could summon the former in a single, sharp image:

[D]ownstairs at the kitchen window

eating the nuts we provide daily

there are twittering small birds –

certainly green finches

(I call them linnets)

and a great tit –

I saw him again this morning –

and sometimes, quite often, blue tits

like chorus girls, when the linnets allow.

(‘We Must Eat a Bird for Christmas’)

How preferable this delicate twittering of fifty years ago to today’s crass, unthinking gibberish! Yet Ure can also smuggle a whole artistic manifesto into a few small lines, themselves starkly modern in their lineation and minimal use of punctuation marks:

I’m glad a crocus has

the sense to know itself

part of a shape which

may not always be just

but is beautiful.

It is the lack of justice

that leaves one

something to do.

(‘To a too modest friend’)

Indeed, it seems to be one purpose of the poems – and the editors, in selecting and presenting them in the way they have? – to affirm that the former need not preclude the latter. “Don’t drown us out of this world,” Ure declares at the close of ‘In Memoriam 1971’, a poem replete with tales of the world squashing women flat with expectation, “it could be springtime”. Or the whole mid-sixties fragment of ‘from ‘Words and Music’’, in its uncanny parallels with 2014 (and indeed both 2016 and 2019):

Oh I am sick

to bloody death

from the gritty No

of a sour people

sick sick to death

And now I go

I sharpen my stainless skates

and I skate wild

on the frozen Yes

of my own joy

my joy, alone.

How about you?

Occasionally, Ure veers too far in one or other of these directions (and at least in this selection, towards plainer political statements). In ‘My Year for Being Resentful is Over’, for instance, the anger which animates the other poems, breaking the surface now and again in clever darts of satire or wry observation, comes through too overtly – no matter its truth – and nudges the work away from poetry, towards polemic:

It would be better to be secondrate

or if I’m secondrate anyway, it is obvious

that it would be better to be third class

for then I wouldnt have to convince

anybody that not understanding my stuff

on the page doesnt guarantee my superiority

and therefore is not causing an offence.

Despite the Editors’ Notes assuring us that “as far as possible, [we] have adhered faithfully to the original manuscript and typescript versions”, the evident bitterness at being thwarted which comes through here – as a poet and dramatist, a woman, perhaps simply an intelligent person in a culture of rigid conformity – seems to me to be distorting the poet’s sensibility, fracturing her grammar and sending meaning crashing out too fiercely line after line. In these poems Ure is at her best when she steers a middle course – writing through experience to a keen, lived conclusion which will change the reader in the reading, but embedding the lesson in a rich image which amplifies its power, making it forceful and memorable where one more line in a manifesto would not be. Piercing, even heart-breaking as it is, the lover’s unvarnished analysis which concludes ‘Signal at Red’ captures the power of this collection in a single picture:

I think I de-

cipher in your

biblical sim-

plicity your own

impersonal Love

living lonely in

its vacuum and

wanting no kiss?

If it is not so

then my signal

is flashing – no

healthy heart is

safe with me.

I am a cracked &

crooked mirror &

can give back no

reflection.

It is the heart

unduplicated,

not the mirror,

that will break.

Jul 26 2019

London Grip Poetry Review – Joan Ure

James Roderick Burns is moved by a thoughtfully chosen selection of Joan Ure’s defiant poetry

Reading The Tiny Talent is both a bracing and a saddening experience. Bracing for its content – acerbic, culturally-engaged, defiant verse that seems to have come from the darkest of places determined to bring light; saddening in that at 22 poems, barring any additional selections, it feels more like a poet consolidating beginnings than drawing things to a close.

One of the editors of the volume, Richie McCaffery, has written an excellent biographical and critical sketch about the woman who took on the world as Joan Ure (https://www.scottishpoetrylibrary.org.uk/poet/joan-ure/ – incidentally a site as good as the Scottish Poetry Library itself). It charts the life and literary development of Elizabeth Carswell (Elizabeth Clark after her marriage) from grim, strangled family beginnings (“Ure’s grandfather, a foreman, often spent an evening seated alone in the best parlour of his house, consuming a bottle of whisky in perfectly orderly silence”) through forced obedience to social norms, a partial break-out through drama and poetry – the two often fusing in The Tiny Talent within monologues and other forms brimming with performative energy – and the adoption of a protective nom-de-plume, to a unique voice combining ‘poetic’ lyricism with hard-bitten determination for change.

Ure could summon the former in a single, sharp image:

[D]ownstairs at the kitchen window eating the nuts we provide daily there are twittering small birds – certainly green finches (I call them linnets) and a great tit – I saw him again this morning – and sometimes, quite often, blue tits like chorus girls, when the linnets allow. (‘We Must Eat a Bird for Christmas’)How preferable this delicate twittering of fifty years ago to today’s crass, unthinking gibberish! Yet Ure can also smuggle a whole artistic manifesto into a few small lines, themselves starkly modern in their lineation and minimal use of punctuation marks:

I’m glad a crocus has the sense to know itself part of a shape which may not always be just but is beautiful. It is the lack of justice that leaves one something to do. (‘To a too modest friend’)Indeed, it seems to be one purpose of the poems – and the editors, in selecting and presenting them in the way they have? – to affirm that the former need not preclude the latter. “Don’t drown us out of this world,” Ure declares at the close of ‘In Memoriam 1971’, a poem replete with tales of the world squashing women flat with expectation, “it could be springtime”. Or the whole mid-sixties fragment of ‘from ‘Words and Music’’, in its uncanny parallels with 2014 (and indeed both 2016 and 2019):

Occasionally, Ure veers too far in one or other of these directions (and at least in this selection, towards plainer political statements). In ‘My Year for Being Resentful is Over’, for instance, the anger which animates the other poems, breaking the surface now and again in clever darts of satire or wry observation, comes through too overtly – no matter its truth – and nudges the work away from poetry, towards polemic:

Despite the Editors’ Notes assuring us that “as far as possible, [we] have adhered faithfully to the original manuscript and typescript versions”, the evident bitterness at being thwarted which comes through here – as a poet and dramatist, a woman, perhaps simply an intelligent person in a culture of rigid conformity – seems to me to be distorting the poet’s sensibility, fracturing her grammar and sending meaning crashing out too fiercely line after line. In these poems Ure is at her best when she steers a middle course – writing through experience to a keen, lived conclusion which will change the reader in the reading, but embedding the lesson in a rich image which amplifies its power, making it forceful and memorable where one more line in a manifesto would not be. Piercing, even heart-breaking as it is, the lover’s unvarnished analysis which concludes ‘Signal at Red’ captures the power of this collection in a single picture:

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • authors, books, poetry reviews, year 2019 0 • Tags: books, James Roderick Burns, poetry