May 9 2019

London Grip Poetry Review – Helen Dunmore

D A Prince is intrigued by the presentation but delighted by the substance of this substantial retrospective collection of Helen Dunmore’s poetry

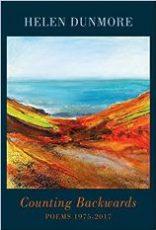

Counting Backwards: Poems 1975 – 2017 Helen Dunmore Bloodaxe Books, 2019. ISBN 978-1-78037-445-1 £14.99

The title is appropriate because if you intend to read this large collection as you would any other book – that is, starting at the beginning and working through the sections in order – counting backwards exactly is what you will be doing. This substantial selection from Dunmore’s poetry opens with her final collection (Inside the Wave, 2017) and then takes the reader back in time through earlier collections until her debut (The Apple Fall, 1983). Her last four collections (as far back as Out of the Blue, 2001) are published in full; earlier collections are represented by sizeable selections. It’s still unusual to encounter a poet’s work in this way: a glance over my shelves shows that publishers have a preference for chronological order, starting with the early poems. Bloodaxe, however, had taken the same approach in an earlier selection of Dunmore’s poetry (Out of the Blue: poems 1975 -2001) so we know Dunmore has previously approved this entry point as well as the selections from earlier work.

I wonder how many readers would ever tackle a major selection by reading through in order whichever way the chronology runs? It takes a large block of time and even if you are familiar with all the previous collections it’s likely that some sections will have faded from memory. This isn’t to diminish the poems but rather to acknowledge the reality that we cannot remember all we read – and that, as individuals, we will remember different poems. Yet whenever I’ve read a ‘collected’ or a major selected from start to finish it’s been a rewarding experience, bringing a closeness to the poet’s themes and development in a way that reading single collections, years apart, hasn’t provided. The depth and immersion have felt worthwhile. However, those have all opened with the early works: reading backwards imposes an additional strain, that of unpicking the poet’s journey and trying to see where the strengths first appeared. It’s akin to listening to Stephen Sondheim’s Merrily We Roll Along where the characters become their younger, more hopeful selves and the same musical motifs appear but in different contexts. It works in a musical but is it the best way to engage with a poet’s work across a lifetime’s writing?

Inside the Wave won the Costa Poetry Award in 2017 and subsequently the Costa Book of the Year. It was a posthumous award; Dunmore had died in early June. These are poems written while facing death, and are predominantly contained within hospital wards and memories; there is a spareness about them and a muted tonal palette. Is it too soon to look objectively at this collection as a whole? – perhaps. Bloodaxe chose to use capital letters for the start of each line when publishing the single volume, and they have retained the same style here, even though the rest of Counting Backwards uses lower case; it’s a small detail but it marks out Inside the Wave visually, and seems an odd inconsistency. So it was with The Malarkey (2012) that I felt on surer ground. The title poem won the National Poetry Competition in 2010 and its ambiguity has lost nothing of its power: is the ‘you’ a self-reflective use or it closer to a short story? What is happening, exactly?

You looked away just once as you leaned on the chip-shop counter, and forty years were gone.

The language is simple but it holds a mystery. It’s a reminder of Dunmore’s subtle and allusive way with the short story as a form. When she brings the same approach into poems, as in ‘Out of the blue’ (from Out of the Blue, 2001) or ‘Little Ellie’ (from Bestiary, 1997), it’s as though the story-content grows organically out of the surrounding poems, which may be lyric, or personal or observational, or all three combined. The Malarkey contains two short stories in prose: ‘Writ in water’ (Keats’ death as told by Joseph Severn) and ‘Taken in Shadows’ (a first-person response to John Donne’s portrait) which runs to five pages. These are unexpected but, reaching out as they do as a reminder of Dunmore’s four short story collections, they sit well in this retrospective and show how closely – for her – the genres are allied.

Both Out of the Blue and Bestiary contain versions from Piers Plowman. ‘Need’, the earlier (in time) reflects some of the social concerns that are present throughout this book – poverty, homelessness, the struggle for food, employment, disease, imprisonment. Dunmore is incapable of polemic and these concerns thread through quiet, watchful poems, often drawn from her walks through familiar city streets, sometimes with her own children. That makes the underlying message all the more powerful; her concerns are embedded in her poems rather than attached to current news stories, labelled with date and time – so two poems on the first Iraq War come as a shock. And although she writes about her own children she transcends the merely anecdotal; in her poems the children become universal, standing in for childhood with its joys and sunlight but also its vulnerability. Has anyone ever written better about seaside holidays and swimming? Yet she is conscious of dangers, particularly concerned about ‘men in cars’ and young girls; the fear of abduction is never far away; and while she never names specific stories we can remember names, headlines, photographs. It’s a subject that doesn’t go away and surfaces, in some way, in each collection,. In Recovering a Body (1994), the opening poem ‘To Virgil’ asks for guidance out of the reality of the underground and the precise details that make rush hour travel into its own hell, as well as its fears.

If there are incidents, let them be over, let there be no red-and-white tape marking the place, make it not happen when the tunnel has wrapped its arms round my train and the lights have failed.

This was the collection to which she wrote an Afterword, explaining how the poems related to the body and its instability, as though the poems by themselves couldn’t contain the strength of her recognition of rapid and terrifying change. To read her words now brings Inside the Wave back into sharp focus: “People in the rich West stay late-middle-aged for so long now. The years tick on and then suddenly, astonishingly, the world narrows to a white bed and the wink of the electrocardiograph.”

Helen Dunmore is another poet who died too young. Reading her poems, all those she wished to preserve, has been a revelation. In them her voice is consistently clear, and her intelligence probes delicately and with precision into the universal underpinning the ordinariness of the everyday, of our everyday. She can balance the light and dark of the four and a half decades of her writing life in seemingly effortless lines. Whether you read them as Bloodaxe intends, or start at the back with the early work, having these poems together in one volume is life-enhancing.

05/07/2019 @ 20:28

I would like to thank D A Prince for this excellent, appreciative review, but knowing how a fine review such as this – readily available on the internet – is likely to be read and re-read long after its first publication I feel I must correct a wrong assumption about the editing of Helen Dunmore’s work which she makes here: “Bloodaxe chose to use capital letters for the start of each line when publishing the single volume [Inside the Wave], and they have retained the same style here, even though the rest of Counting Backwards uses lower case; it’s a small detail but it marks out Inside the Wave visually, and seems an odd inconsistency.” Poetry publishers do not – or should not – decide stylistic choices of this kind, which are very much personal for the poet. It was Helen Dunmore who decided to use capital letters for the start of each line in Inside the Wave, and as her editor for thirty years it was inevitable that I should query this with her when she submitted the original manuscript in 2016. She responded: “The initial capitals on the line – I know this is new for me although it is what I’ve been doing more and more over the past two or three years. It seems right – I like the emphasis and a certain shape that it gives to the line.” The manuscript underwent many changes before the book was published shortly before Helen’s death in 2017 but the initial capitals stayed. Later, when editing Counting Backwards, I was obliged to follow Helen’s wishes in all respects, and indeed, the contract with her estate specified that the texts of all the poems should not be changed in any way from those approved by Helen for publication in Inside the Wave and the previous collections.