D A Prince appreciates the subtle way in which the two parts of Carol DeVaughn’s collection fit together

Life Class

Carol DeVaughn

Oversteps Books, 2018

ISBN 978-1-906856-81-6

£8.

At first sight this seems a collection of two halves. Life Class opens with twenty-eight poems on various subjects (although many are prompted by the visual arts) to be followed by the twenty-five poem sequence which gives the collection its title. Only after the initial reading does the connection become clear, as the sequence “Life Class” explores what it is like to be the silent subject of close observation – the model for a life-drawing class – while the earlier poems examine art from the observer’s side. The ekphrastic poems gain depth from the personal experience of being the subject of art – an experience that is impersonal. The students focus on the body while the model focuses on: what, exactly? Taken as a whole this makes for an intriguing and thought-provoking examination of the art of looking. ‘How much looking/ is needed to see beyond the form?’ asks the poet in “Life Class (ii)”, a question that sends the reader back to the beginning of the book to try to answer that question.

DeVaughn’s voice is quiet, as suits her role as an active observer, one who wishes to see beyond the surface. In “A Meeting of Angels” she considers how to look at a white marble sculpture, a group of angels, trying to understand the relationship between the physical weight of marble and the angels’ other-worldly quality.

Our breathing stops, then deepens;

we keep listening, waiting

for buried chords to bring coherence,

for feathers, even with burnt edges,

to break surface, fly free.

The same sense of music contained within an object, part of the unseen identity, is picked up in “Airport Chapel” – ‘A room full of hum / where prayers speak in tongues’. It is colour, however, that speaks to the artist in DeVaughn, and which allows her to bring together layers of experience. In the beautifully compact love poem “Spring Snowfall; for J” she can balance herself, and John, and the one-minute snow fall seen through a window against the collage of

golden white spray of broom

cranberry red camellia heads

fir tree

blackbird with orange beak…

The immediacy of the colours defines the intensity of the moment. She has a way of using double-spacing to allow images, especially colours, to stand separate and to allow time for the reader’s inner eye to catch up with the words on the page; we see the effects of this in “A Kind of Blue” and “Horizon”, where the ‘two shades of grey’ that are sea and sky give the tone of the whole poem. She doesn’t over-use this technique, despite its effectiveness; in “On Rothko” the conventional spacing evokes the close bands of colour can ‘reveal the geology of feeling’ of his paintings.

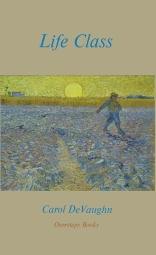

Van Gogh’s paintings hold a strong attraction for De Vaughn; his work is central to five poems, and his colours and landscapes are a presence in others. His painting ‘The Sower’ is on the cover as well as providing the impetus for one of the strongest poems in this section, “Sower at Sunset”. It opens–

He wants to show you the field he keeps seeing

in his mind’s eye, the field that makes him sizzle,

the field with the blinding yellow sun–

his favourite colour–the yellow that sends cerulean

down to ground, reversing the order of things.

A dramatic opening, and it takes us into Van Gogh’s intentions: ‘He wants …’, ‘He feels …’, ‘He looks …’, ‘He makes …’ These are all line-beginnings, repeated through the poem, emphasising through words the artist’s desire to have colour pulsing across his canvas. When poems are as powerful in their writing as this it would be easy to overlook some of the poems in a softer register, so I want to point out “Bird in an Air Pump; after Joseph Wright of Derby”; only twelve lines but they get to the heart of this group portrait through the eyes of the small boy watching the experiment. As with Van Gogh, DeVaughn takes us in through the ‘mind’s eye’—

Unlike my sister, I’d rather know

the truth about shadows

and the darker side of light.

I’m afraid but force myself to watch,

see whether the bird’s wings stay open,

rise like this night’s full moon.

It’s this ‘truth’ of looking, the interplay of light and shadow’, that opens the door into “Life Class”, the final sequence that shows an unfamiliar side of art: what it is like to be the focus of attention as a life model. Silent, motionless, with only her intimate thoughts and imaginings to occupy the passing hours, and with only a limited space to look at, DeVaughn moves fluidly through the physical self-control and mental stamina required for the task. She begins with the physical aspects –

It’s the hardest pose – the thinker lying down, resting

on the elbow, cheek on cupped palm.

How many times have you seen this pose in a drawing, not considering how the body would set into this shape? ‘I re-align my spine, re-gear my joints before daring/ to stand …’ she writes, before she can ‘Amaze myself by walking across the room.’ By the end of this short poem we share the feel of stiffness, the relief of movement. Only then does DeVaughn take us into her visual field, the patch of paint-flecked studio wall and colours that seem brighter because she cannot turn away from them.

The wall is sky blue

with old spatterings of scarlet,

cadmium yellow, and burnt orange–

fiery suns on azure field.

There’s an echo of her poem on Van Gogh’s sower in these colours; they re-appear, variously, through this sequence, as do the sparrow and wren, glimpsed on the windowsill. When your view is fixed, when you have to concentrate so that others can concentrate, the tiniest detail becomes significant. The students’ concentration is palpable –

they draw my back

with charcoal. I hear their marks,

sense the sweep of lines

and sudden scrawls

criss-crossing my spine,

burrowing between the blades,

mining a new territory

of light and shade.

Later, they will ‘… go deeper than my skin. […] digging for what they cannot see.’ For the model a lopsided spot of red paint becomes Jupiter’s Giant Red Spot. In another pose, curled into an armchair her imagination lets her become a bear, or explore the wildlife of the Himalayas, or inhabit remembered paintings; it all rises out of the starting point of stillness. Her mind can explore the wider world while her body is motionless.

Re-reading the first half of the collection after the intense, centred immobility of this sequence is to see DeVaughn’s poems with new eyes and deeper awareness, both for the surface texture and for her sensitivity to every movement and colour. She ends with the lines ‘we share nakedness/ and the uncertainty of flesh and bone’, a lightness that returns us in a very satisfying way to the opening poem, where the viewers are aligning themselves with the angels.

Feb 11 2019

London Grip Poetry Review – Carol DeVaughn

D A Prince appreciates the subtle way in which the two parts of Carol DeVaughn’s collection fit together

At first sight this seems a collection of two halves. Life Class opens with twenty-eight poems on various subjects (although many are prompted by the visual arts) to be followed by the twenty-five poem sequence which gives the collection its title. Only after the initial reading does the connection become clear, as the sequence “Life Class” explores what it is like to be the silent subject of close observation – the model for a life-drawing class – while the earlier poems examine art from the observer’s side. The ekphrastic poems gain depth from the personal experience of being the subject of art – an experience that is impersonal. The students focus on the body while the model focuses on: what, exactly? Taken as a whole this makes for an intriguing and thought-provoking examination of the art of looking. ‘How much looking/ is needed to see beyond the form?’ asks the poet in “Life Class (ii)”, a question that sends the reader back to the beginning of the book to try to answer that question.

DeVaughn’s voice is quiet, as suits her role as an active observer, one who wishes to see beyond the surface. In “A Meeting of Angels” she considers how to look at a white marble sculpture, a group of angels, trying to understand the relationship between the physical weight of marble and the angels’ other-worldly quality.

The same sense of music contained within an object, part of the unseen identity, is picked up in “Airport Chapel” – ‘A room full of hum / where prayers speak in tongues’. It is colour, however, that speaks to the artist in DeVaughn, and which allows her to bring together layers of experience. In the beautifully compact love poem “Spring Snowfall; for J” she can balance herself, and John, and the one-minute snow fall seen through a window against the collage of

The immediacy of the colours defines the intensity of the moment. She has a way of using double-spacing to allow images, especially colours, to stand separate and to allow time for the reader’s inner eye to catch up with the words on the page; we see the effects of this in “A Kind of Blue” and “Horizon”, where the ‘two shades of grey’ that are sea and sky give the tone of the whole poem. She doesn’t over-use this technique, despite its effectiveness; in “On Rothko” the conventional spacing evokes the close bands of colour can ‘reveal the geology of feeling’ of his paintings.

Van Gogh’s paintings hold a strong attraction for De Vaughn; his work is central to five poems, and his colours and landscapes are a presence in others. His painting ‘The Sower’ is on the cover as well as providing the impetus for one of the strongest poems in this section, “Sower at Sunset”. It opens–

A dramatic opening, and it takes us into Van Gogh’s intentions: ‘He wants …’, ‘He feels …’, ‘He looks …’, ‘He makes …’ These are all line-beginnings, repeated through the poem, emphasising through words the artist’s desire to have colour pulsing across his canvas. When poems are as powerful in their writing as this it would be easy to overlook some of the poems in a softer register, so I want to point out “Bird in an Air Pump; after Joseph Wright of Derby”; only twelve lines but they get to the heart of this group portrait through the eyes of the small boy watching the experiment. As with Van Gogh, DeVaughn takes us in through the ‘mind’s eye’—

It’s this ‘truth’ of looking, the interplay of light and shadow’, that opens the door into “Life Class”, the final sequence that shows an unfamiliar side of art: what it is like to be the focus of attention as a life model. Silent, motionless, with only her intimate thoughts and imaginings to occupy the passing hours, and with only a limited space to look at, DeVaughn moves fluidly through the physical self-control and mental stamina required for the task. She begins with the physical aspects –

How many times have you seen this pose in a drawing, not considering how the body would set into this shape? ‘I re-align my spine, re-gear my joints before daring/ to stand …’ she writes, before she can ‘Amaze myself by walking across the room.’ By the end of this short poem we share the feel of stiffness, the relief of movement. Only then does DeVaughn take us into her visual field, the patch of paint-flecked studio wall and colours that seem brighter because she cannot turn away from them.

There’s an echo of her poem on Van Gogh’s sower in these colours; they re-appear, variously, through this sequence, as do the sparrow and wren, glimpsed on the windowsill. When your view is fixed, when you have to concentrate so that others can concentrate, the tiniest detail becomes significant. The students’ concentration is palpable –

Later, they will ‘… go deeper than my skin. […] digging for what they cannot see.’ For the model a lopsided spot of red paint becomes Jupiter’s Giant Red Spot. In another pose, curled into an armchair her imagination lets her become a bear, or explore the wildlife of the Himalayas, or inhabit remembered paintings; it all rises out of the starting point of stillness. Her mind can explore the wider world while her body is motionless.

Re-reading the first half of the collection after the intense, centred immobility of this sequence is to see DeVaughn’s poems with new eyes and deeper awareness, both for the surface texture and for her sensitivity to every movement and colour. She ends with the lines ‘we share nakedness/ and the uncertainty of flesh and bone’, a lightness that returns us in a very satisfying way to the opening poem, where the viewers are aligning themselves with the angels.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • art, books, poetry reviews, year 2019 0 • Tags: art, books, D A Prince, poetry