Mining the Motherlode: Brian Docherty finds Jacqueline Saphra to be an entertaining narrator whether or not she is an unreliable one.

All My Mad Mothers

Jacqueline Saphra

Nine Arches Press, 2017

ISBN 978-1-911027-20-1

72pp £9.99

All My Mad Mothers

Jacqueline Saphra

Nine Arches Press, 2017

ISBN 978-1-911027-20-1

72pp £9.99

This is Saphra’s second full collection, incorporating most of the prose poems from the wonderfully titled If I Lay on My Back I Saw Nothing but Naked Women (Emma Press, 2014). The illustrations from this publication are not included, but nonetheless, All My Mad Mothers is two books in one, with the prose poems interspersed with the other work. Mothering, motherhood, childhood, and adolescence feature strongly in an apparently confessional mode that announces our old friend the Unreliable Narrator. Whether readers take the candour of some of these poems as revealing anything about Saphra’s life experience is entirely up to them. Entertaining, these poems certainly are. The book’s title could be literal, metaphorical, feminist, or some combination of all three.

Section 1 of the book opens with ‘In the winter of 1962 my mother’, a 3rd person eight line anecdote of a baby being driven round Hyde Park Corner, a metaphor for problems in the relationship between the baby’s parents. If this is the same person or persona in later poems, the narrator in ‘My Mother’s Bathroom Armoury’ is looking back at her childhood self, the poem finishing

Mother’s tricks will pass to daughter

This year next year sometime never

This could be viewed from some people’s perspectives as an outdated model of femininity, or what it might mean to be a woman in the twentieth century. We then move on to ‘Sicily’, a holiday experience poem set in the late 1960s, as contextualised by references to Ho Chi Minh, and Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. What we get, apart from the socio-political referents, is a ‘you show me yours / I’ll show you mine’ involving a group of safely pre-pubescent children. The 1960s are also referenced in ‘The Sound of Music’, still many people’s favourite musical over 50 years on. The narrator’s sister gets a bit part, before overdosing on drugs or prescription medication, the poem concluding

Maybe I should have told her

I didn’t understand then

that you can squander a lifetime

trying to stay small and pretty

believing you have the voice

of an angel if only someone

would hear it and carry you

up the grand staircase to bed.

The book’s title poem, in seven quatrains, closes the first section. Each stanza opens ‘My mother’, and we are invited to consider whether this poem is seven portraits of one woman, seven characters or personas, or seven representative women, important to the narrator in some way. Inventions or not, each quatrain, in other hands, could start a poem of its own. The last one for example, reads

My mother was so hard to grasp: once we found her

in a bath of extra virgin olive oil, her skin well slicked.

She’s stocked the fridge with lard and suet, butter – salted

and unsalted – to ease her way into the world. Or out of it.

Section 2 shows the narrator as a young woman, say 18 or 19, between say 1978 and 1980. (Your unreliable reviewer’s arithmetic may be suspect here). ‘Crete 1980’ may show what we would now call a Gap Year; written in couplets, appropriate for a poem featuring coupling, where

I was girlish and abandoned, taking my bed

of sand, those oh-so-green and casual boys

for granted, dreamed in beaches

naked, mouth grazed with the taste

of smoke and strangers’ kisses,

and I howled into the drunken dark for

stupid reasons and I thought

this was an education.

Voyage of discovery, rite of passage, indeed. Oh, such pre-AIDS innocence. Other poems set in this period take us to Hampstead, Paris, a kibbutz, and Mile End, among other locations. ‘Things We Can’t Untie’ features two teenage lovers with different tastes in music, her with Songs of Leonard Cohen, him with The Clash’s ‘Guns of Brixton’ (released in December 1979), a metaphor for two young people going in different directions. ‘Like a Fish Needs a Bicycle‘ , a classic feminist mantra from this period, shows the narrator’s mother meeting ‘my little brother’s new friend’s mothers‘ who happen to be openly gay, and yes, mother asks them “Please could they teach her how to be a lesbian?”

More teenage encounters for our narrator follow in ‘Virginity‘, ‘‘The Day My Cousin Took Me to the Musée Rodin‘ (and propositioned her), ‘Volunteers, 1978‘, and ‘Hampstead, 1979’. This time,

He says he’s a Gemini too,

always wears white linen

to parties and is a recreational

heroine user in an open

relationship.

Of course, sex follows, as it does in ‘My Friend Juliet’s Icelandic Lover’ , which might be set in University or Drama College, . This section concludes in ‘Mile End’, which is addressed to an unnamed friend or former lover, references ‘that bistro in Curzon Street’ in 1981, before arriving in the poem’s titular London some time later.

In Section 3, some time has obviously passed, our narrator now has children, and what passes for a domestic life. The poems in this section are quite different, with some approaching the status of parable, as in ‘Mother. Son. Sack of Salt’, where two people carry a sack of salt home.

It’s heavier than it looks,

but she’s strong, it’s nothing

and he can help. She takes

one end, he takes the other.

The poem finishes

She turns back; follows the trail

of white. She tries to gather up

everything they’ve left behind,

to fill her arms with salt.

‘Leavings’ is a parable quite unlike most of the earlier poems in the book, feeling more like a Country song (not Nashville, but recent Americana). It starts

The devils and the lunatics are loose;

bear your children, keep them close

for now

and finishes

throw up your wrinkled hands, unveil the wreck

you’ve left them: the fires, the slow black,

the cleft and spill. Confess: this bruised world, blue

and plundered; now it belongs to you.

‘What Time is it in Nova Scotia’ is a prose poem, addressed to an adult daughter who has left home, more ambitious, less domestic, despite the title’s filmic quality – a ‘letting go’ poem to a daughter, the inverse of the earlier ‘rite of passage’ poems. This section closes with ‘The Doors to My Daughter’s House’, where the daughter is her person in every sense, and this poem again approaches the status of parable ,

I’ve seen her stride away through meadows

of folding light, to the place where the brow of the hill

meets the orchards I planted for her long ago.

I’ve watched her fill her pack with gold and red.

This unspecified location is not a London, Crete, Paris, we can recognise,

. where she stands honed and ready

as the newest weathers of the world rush in and all

her tomorrows poise to make their entrances.

In Section 4, we appear to be in a nominal present, where in ‘Reincarnation’, the narrator wishes to come

back as a skink, whereas in ‘Kiss/Kiss’, a well executed villanelle,

. Love comes around again, hot pulse in the chest,

so unexpected, so familiar. You pull up a chair,

and when we kiss the way we always kiss,

It’s clear that mature trumps young love every time, leaving the reader with “Let’s kiss, my love, the way we always kissed.”

‘The Anchor’ is a quite different, and frankly odd, love poem, using the metaphor of an anchor and chain, while ‘Spunk’ an ekphrastic poem responding to Jacob Epstein’s sculpture Adam, focusses on the figure’s penis. This sonnet concludes “Must this man be the father of us all?” Discuss. (If you are a feminist, possibly not.)

‘Soup’ is another contrast to previous poems, where two old friends meet for lunch, and a chance to discuss an upcoming wedding, its related complications, and possible outcomes. ‘Valentine for Late Love’ is a 14 line poem (a modern sonnet I suppose) which could be addressed to the same recipient as ‘Kiss/Kiss’, while the book’s final poem, ‘Charm for Late Love’ could possibly be a cutup of Robert Burns’ ‘John Anderson my Jo’ and the mediaeval ballad, ‘The Lyke Wake Dirge’. It finishes

Let’s hunt the heart we’ll never keep.

Candle Gutter Snuff and Sleep.

Indeed. This book moves a long way from its opening to this closing note.

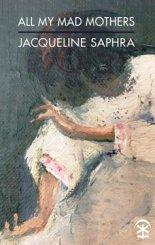

The more alert readers will have noticed that I have not discussed the interspersed prose poems from the Emma Press publication. This is still available from the publisher if you wish to enjoy the illustrations in tandem with the writing; but in relation to the present book, they are your bonus ball, an unexpected treat. Saphra and Nine Arches Press are to be commended for arranging the book in this way. The volume, as with most small press publications now, is well presented and printed, with cover art from Laurence Hope (an Australian painter, I believe), whose painting, only part of which is reproduced, might reference the ‘mad women in the attic‘ from Jane Eyre, or the character of Antoinette from Jean Rhys’ Wide Sargasso Sea. (Anyone more familiar with Laurence Hope’s oeuvre can send the editor their comments or corrections). I look forward to reading Jacqueline Saphra’s subsequent work.

Mining the Motherlode: Brian Docherty finds Jacqueline Saphra to be an entertaining narrator whether or not she is an unreliable one.

This is Saphra’s second full collection, incorporating most of the prose poems from the wonderfully titled If I Lay on My Back I Saw Nothing but Naked Women (Emma Press, 2014). The illustrations from this publication are not included, but nonetheless, All My Mad Mothers is two books in one, with the prose poems interspersed with the other work. Mothering, motherhood, childhood, and adolescence feature strongly in an apparently confessional mode that announces our old friend the Unreliable Narrator. Whether readers take the candour of some of these poems as revealing anything about Saphra’s life experience is entirely up to them. Entertaining, these poems certainly are. The book’s title could be literal, metaphorical, feminist, or some combination of all three.

Section 1 of the book opens with ‘In the winter of 1962 my mother’, a 3rd person eight line anecdote of a baby being driven round Hyde Park Corner, a metaphor for problems in the relationship between the baby’s parents. If this is the same person or persona in later poems, the narrator in ‘My Mother’s Bathroom Armoury’ is looking back at her childhood self, the poem finishing

Mother’s tricks will pass to daughter This year next year sometime neverThis could be viewed from some people’s perspectives as an outdated model of femininity, or what it might mean to be a woman in the twentieth century. We then move on to ‘Sicily’, a holiday experience poem set in the late 1960s, as contextualised by references to Ho Chi Minh, and Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. What we get, apart from the socio-political referents, is a ‘you show me yours / I’ll show you mine’ involving a group of safely pre-pubescent children. The 1960s are also referenced in ‘The Sound of Music’, still many people’s favourite musical over 50 years on. The narrator’s sister gets a bit part, before overdosing on drugs or prescription medication, the poem concluding

Maybe I should have told her I didn’t understand then that you can squander a lifetime trying to stay small and pretty believing you have the voice of an angel if only someone would hear it and carry you up the grand staircase to bed.The book’s title poem, in seven quatrains, closes the first section. Each stanza opens ‘My mother’, and we are invited to consider whether this poem is seven portraits of one woman, seven characters or personas, or seven representative women, important to the narrator in some way. Inventions or not, each quatrain, in other hands, could start a poem of its own. The last one for example, reads

My mother was so hard to grasp: once we found her in a bath of extra virgin olive oil, her skin well slicked. She’s stocked the fridge with lard and suet, butter – salted and unsalted – to ease her way into the world. Or out of it.Section 2 shows the narrator as a young woman, say 18 or 19, between say 1978 and 1980. (Your unreliable reviewer’s arithmetic may be suspect here). ‘Crete 1980’ may show what we would now call a Gap Year; written in couplets, appropriate for a poem featuring coupling, where

I was girlish and abandoned, taking my bed of sand, those oh-so-green and casual boys for granted, dreamed in beaches naked, mouth grazed with the taste of smoke and strangers’ kisses, and I howled into the drunken dark for stupid reasons and I thought this was an education.Voyage of discovery, rite of passage, indeed. Oh, such pre-AIDS innocence. Other poems set in this period take us to Hampstead, Paris, a kibbutz, and Mile End, among other locations. ‘Things We Can’t Untie’ features two teenage lovers with different tastes in music, her with Songs of Leonard Cohen, him with The Clash’s ‘Guns of Brixton’ (released in December 1979), a metaphor for two young people going in different directions. ‘Like a Fish Needs a Bicycle‘ , a classic feminist mantra from this period, shows the narrator’s mother meeting ‘my little brother’s new friend’s mothers‘ who happen to be openly gay, and yes, mother asks them “Please could they teach her how to be a lesbian?”

More teenage encounters for our narrator follow in ‘Virginity‘, ‘‘The Day My Cousin Took Me to the Musée Rodin‘ (and propositioned her), ‘Volunteers, 1978‘, and ‘Hampstead, 1979’. This time,

He says he’s a Gemini too, always wears white linen to parties and is a recreational heroine user in an open relationship.Of course, sex follows, as it does in ‘My Friend Juliet’s Icelandic Lover’ , which might be set in University or Drama College, . This section concludes in ‘Mile End’, which is addressed to an unnamed friend or former lover, references ‘that bistro in Curzon Street’ in 1981, before arriving in the poem’s titular London some time later.

In Section 3, some time has obviously passed, our narrator now has children, and what passes for a domestic life. The poems in this section are quite different, with some approaching the status of parable, as in ‘Mother. Son. Sack of Salt’, where two people carry a sack of salt home.

It’s heavier than it looks, but she’s strong, it’s nothing and he can help. She takes one end, he takes the other.The poem finishes

She turns back; follows the trail of white. She tries to gather up everything they’ve left behind, to fill her arms with salt.‘Leavings’ is a parable quite unlike most of the earlier poems in the book, feeling more like a Country song (not Nashville, but recent Americana). It starts

The devils and the lunatics are loose; bear your children, keep them close for nowand finishes

‘What Time is it in Nova Scotia’ is a prose poem, addressed to an adult daughter who has left home, more ambitious, less domestic, despite the title’s filmic quality – a ‘letting go’ poem to a daughter, the inverse of the earlier ‘rite of passage’ poems. This section closes with ‘The Doors to My Daughter’s House’, where the daughter is her person in every sense, and this poem again approaches the status of parable ,

I’ve seen her stride away through meadows of folding light, to the place where the brow of the hill meets the orchards I planted for her long ago. I’ve watched her fill her pack with gold and red.This unspecified location is not a London, Crete, Paris, we can recognise,

. where she stands honed and ready as the newest weathers of the world rush in and all her tomorrows poise to make their entrances. In Section 4, we appear to be in a nominal present, where in ‘Reincarnation’, the narrator wishes to come. Love comes around again, hot pulse in the chest, so unexpected, so familiar. You pull up a chair, and when we kiss the way we always kiss,It’s clear that mature trumps young love every time, leaving the reader with “Let’s kiss, my love, the way we always kissed.”

‘The Anchor’ is a quite different, and frankly odd, love poem, using the metaphor of an anchor and chain, while ‘Spunk’ an ekphrastic poem responding to Jacob Epstein’s sculpture Adam, focusses on the figure’s penis. This sonnet concludes “Must this man be the father of us all?” Discuss. (If you are a feminist, possibly not.)

‘Soup’ is another contrast to previous poems, where two old friends meet for lunch, and a chance to discuss an upcoming wedding, its related complications, and possible outcomes. ‘Valentine for Late Love’ is a 14 line poem (a modern sonnet I suppose) which could be addressed to the same recipient as ‘Kiss/Kiss’, while the book’s final poem, ‘Charm for Late Love’ could possibly be a cutup of Robert Burns’ ‘John Anderson my Jo’ and the mediaeval ballad, ‘The Lyke Wake Dirge’. It finishes

Let’s hunt the heart we’ll never keep. Candle Gutter Snuff and Sleep.Indeed. This book moves a long way from its opening to this closing note.

The more alert readers will have noticed that I have not discussed the interspersed prose poems from the Emma Press publication. This is still available from the publisher if you wish to enjoy the illustrations in tandem with the writing; but in relation to the present book, they are your bonus ball, an unexpected treat. Saphra and Nine Arches Press are to be commended for arranging the book in this way. The volume, as with most small press publications now, is well presented and printed, with cover art from Laurence Hope (an Australian painter, I believe), whose painting, only part of which is reproduced, might reference the ‘mad women in the attic‘ from Jane Eyre, or the character of Antoinette from Jean Rhys’ Wide Sargasso Sea. (Anyone more familiar with Laurence Hope’s oeuvre can send the editor their comments or corrections). I look forward to reading Jacqueline Saphra’s subsequent work.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2017 0 • Tags: books, Brian Docherty, poetry