The undoubted cleverness in Chrissy Williams’ collection is never merely play but also has purpose, observes D A Prince

Bear

Chrissy Williams

Bloodaxe Books, 2017.

ISBN 978-1-78037-332-4

64 pp £9.95

Bear

Chrissy Williams

Bloodaxe Books, 2017.

ISBN 978-1-78037-332-4

64 pp £9.95

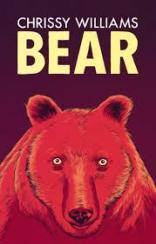

The glossy cover image for Chrissy Williams’ Bear has the solidly physical head of a bear, red and over-size, staring into our space. This is not a menacing figure – in fact, there’s a hint of a smile under his nose – but with even his shoulders cut off he leaves no room for anything else below the title. A book cover’s relationship with the poems is hard to define, except to acknowledge that it plays a significant part: it sets up expectations not just of content but of register. The subtle playfulness of this bear (by Tom Humberstone, an illustrator and creator of comics, and former political cartoonist for the New Statesman) prepares us for – what, exactly? Some poems, or perhaps even a whole sequence, about a solid, real bear ?

The blurb on the rear cover undercuts this neatly in its opening line: “The lively ‘bears’ in this playful and poignant collection will surprise you on every page.” Bears in inverted commas: so, will these be ironic bears? Being unsettled and intrigued is a suitable frame of mind for reading this subtly-connected group of poems, one which seems determined from the outset to overturn any expectations of the reality of bear-ness. The opening lines of the first poem, ‘Bear of the Artist’, present the challenge:

I asked the artist to draw me a heart and instead he drew a bear.

I asked him, What kind of heart is this?’ and he said, ‘It’s not a

heart at all’

I asked him, ‘What kind of bear is this?’ and he said, ‘It’s not a

bear either.’

Confusion? or a way of expressing an emotion, such as the many forms of love, for which no single word is adequate? The artist, the poem continues, is “the one who exists to put bears in your head” – that is, the one who balances this universal need with the fragility of the ‘bear’. Bears disappear, almost, from the surface of the seven epigraph-led sections that make up the collection, until the penultimate poem, ‘The Invisible Bear’, where free verse and prose-poem mingle. The night sky in a planetarium shows the seven stars of The Great Bear

But this bear is invisible. This bear’s joins cannot be seen.

There’s no proof, and no legacy. All I can do is tell you

that your bear is here.

There’s not much comfort in a bear you can see through, but then

in times of not much comfort, reach out for what you can.

This paradox of grasping the invisible, in many forms, has been a constant theme throughout, even when only glanced at, and now brought into the open. Leaving the ‘fake night’ of the planetarium is to return to the real world

Go back, go back, go back. Plant your feet into the earth,

into the Earth. One step at a time is how we have to go.

Out of the dome, the doors are opened. You might say they have been

flung open without ceremony. But stop. Bear. Be dazzled by the daylight.

In the final line ‘Bear’ has taken on another meaning, as a verb: to carry, to carry on – and then to carry this sense of survival into daylight. Earlier poems which at first seemed tangential to the theme start to fit in. ‘Gone’, after Skallagrimmson’s Sonatorrek, moves between a version of the skaldic poem and the twenty-first century, in which a poet faces grief at the death of a son and also celebrates the gift of language that makes expressing this grief possible. The clipped stanzas of ‘from Groundhog Day’ bounce through the repetitions familiar from the film. Similarly, but using an entirely different source in another medium, ’The Lost’, merges various translations of the opening canto of Dante’s Inferno. Repeating the same line in different ways explores and underlines the individual routes through life where the ‘dark wood’ also comes across as ‘a gloomy wood’, ‘a dark forest’, ‘a forest dark’, ‘a shadowed forest’ and where the metaphorical path is variously ‘the right way blurred and lost’, ‘I knew I had lost the way’, ‘I’d wandered off the path’, and ‘The straightforward pathway had been lost.’ Dante’s three-line stanza has in Williams’ hands become three eight-line stanzas, and a poem as much about language and shared experience as the afterlife.

Williams brings the virtual word to the foreground. ‘Robot Unicorn Attack’ is subtitled ‘a love poem for a videogame’ – an unreal world encountered in our own real space and time. If you have a copy of Williams’ pamphlet (Flying into the Bear, HappenStance Press, 2013) you can see that her notes give the web address and describe this as ‘addictive lunacy’ – tempting, but I resisted, although I got as far as noting it has now reached Version 3. At what point do notes to poems become necessary? Sometimes a poem prompts online checking to understand the source; Williams’ pamphlet has notes but this Bloodaxe collection does not. For the poem ‘Manifesto Based on Notes from Lars von Trier’s Five Obstructions’ I was grateful for notes, although other readers might not need them – and there’s enough information in the title to google the source. However, in the gloriously zany ‘Sheep’, which opens

Sheep wearing short pink diner uniforms, serving coffee,

startling easily.

Sheep being followed through evening streets, sensing danger,

flocking helplessly.

Sheep afraid in the nightclub chaos, hooves on the table,

staring blankly.

and which ends

Sheep driving with a shotgun on the empty seat, their own dogs

for protection, as the new life kicks.

the pamphlet’s note – ‘This is a retelling of The Terminator, the female protagonist having been replaced by a flock of sheep.’ – is essential. Would anyone guess? Williams is one who brings a lightness and zest to her notes, a skill which transfers to poems such as ‘There Is an Epigraph’, a found poem of five epigraphs – and one which faces the opening epigraph of the sixth section, ‘We all go a little mad sometimes. words from Norman Bates in Psycho. The levels of play and intertextuality in this collection are an adult mind-game but never with cleverness merely for its own sake. At its heart is a continuing examination of how we engage with the world – or worlds – we live in, how we ‘bear’ our lives. Reality has new dimensions and takes place as much on screens as in the tangible world. In ‘The Burning of the Houses’, the real (the London riots of August 2011) meets the working environment of screens, tweets, links, Facebooking, and videos of kittens. The boundaries between the real and the created are blurring (as with the ‘fake night’ in ‘The Invisible Bear’) as the first four lines show:

Tottenham is on fire and I work in an arts centre

where the sky is blue and I can hear birdsong

from a sound installation of birds

cooing outside my office window.

Online linking is another way of surviving the horror on the streets; friends help you through, even when they have done nothing to put out the flames.

It is a strength of this collection that it has taken so many of the poems from Williams’ pamphlet (thirteen out of the twenty it contains) and lets their themes grow into a book-length set. Each reading finds new connections – the mark of a book that will survive.

The undoubted cleverness in Chrissy Williams’ collection is never merely play but also has purpose, observes D A Prince

The glossy cover image for Chrissy Williams’ Bear has the solidly physical head of a bear, red and over-size, staring into our space. This is not a menacing figure – in fact, there’s a hint of a smile under his nose – but with even his shoulders cut off he leaves no room for anything else below the title. A book cover’s relationship with the poems is hard to define, except to acknowledge that it plays a significant part: it sets up expectations not just of content but of register. The subtle playfulness of this bear (by Tom Humberstone, an illustrator and creator of comics, and former political cartoonist for the New Statesman) prepares us for – what, exactly? Some poems, or perhaps even a whole sequence, about a solid, real bear ?

The blurb on the rear cover undercuts this neatly in its opening line: “The lively ‘bears’ in this playful and poignant collection will surprise you on every page.” Bears in inverted commas: so, will these be ironic bears? Being unsettled and intrigued is a suitable frame of mind for reading this subtly-connected group of poems, one which seems determined from the outset to overturn any expectations of the reality of bear-ness. The opening lines of the first poem, ‘Bear of the Artist’, present the challenge:

I asked the artist to draw me a heart and instead he drew a bear. I asked him, What kind of heart is this?’ and he said, ‘It’s not a heart at all’ I asked him, ‘What kind of bear is this?’ and he said, ‘It’s not a bear either.’Confusion? or a way of expressing an emotion, such as the many forms of love, for which no single word is adequate? The artist, the poem continues, is “the one who exists to put bears in your head” – that is, the one who balances this universal need with the fragility of the ‘bear’. Bears disappear, almost, from the surface of the seven epigraph-led sections that make up the collection, until the penultimate poem, ‘The Invisible Bear’, where free verse and prose-poem mingle. The night sky in a planetarium shows the seven stars of The Great Bear

But this bear is invisible. This bear’s joins cannot be seen. There’s no proof, and no legacy. All I can do is tell you that your bear is here. There’s not much comfort in a bear you can see through, but then in times of not much comfort, reach out for what you can.This paradox of grasping the invisible, in many forms, has been a constant theme throughout, even when only glanced at, and now brought into the open. Leaving the ‘fake night’ of the planetarium is to return to the real world

Go back, go back, go back. Plant your feet into the earth, into the Earth. One step at a time is how we have to go. Out of the dome, the doors are opened. You might say they have been flung open without ceremony. But stop. Bear. Be dazzled by the daylight.In the final line ‘Bear’ has taken on another meaning, as a verb: to carry, to carry on – and then to carry this sense of survival into daylight. Earlier poems which at first seemed tangential to the theme start to fit in. ‘Gone’, after Skallagrimmson’s Sonatorrek, moves between a version of the skaldic poem and the twenty-first century, in which a poet faces grief at the death of a son and also celebrates the gift of language that makes expressing this grief possible. The clipped stanzas of ‘from Groundhog Day’ bounce through the repetitions familiar from the film. Similarly, but using an entirely different source in another medium, ’The Lost’, merges various translations of the opening canto of Dante’s Inferno. Repeating the same line in different ways explores and underlines the individual routes through life where the ‘dark wood’ also comes across as ‘a gloomy wood’, ‘a dark forest’, ‘a forest dark’, ‘a shadowed forest’ and where the metaphorical path is variously ‘the right way blurred and lost’, ‘I knew I had lost the way’, ‘I’d wandered off the path’, and ‘The straightforward pathway had been lost.’ Dante’s three-line stanza has in Williams’ hands become three eight-line stanzas, and a poem as much about language and shared experience as the afterlife.

Williams brings the virtual word to the foreground. ‘Robot Unicorn Attack’ is subtitled ‘a love poem for a videogame’ – an unreal world encountered in our own real space and time. If you have a copy of Williams’ pamphlet (Flying into the Bear, HappenStance Press, 2013) you can see that her notes give the web address and describe this as ‘addictive lunacy’ – tempting, but I resisted, although I got as far as noting it has now reached Version 3. At what point do notes to poems become necessary? Sometimes a poem prompts online checking to understand the source; Williams’ pamphlet has notes but this Bloodaxe collection does not. For the poem ‘Manifesto Based on Notes from Lars von Trier’s Five Obstructions’ I was grateful for notes, although other readers might not need them – and there’s enough information in the title to google the source. However, in the gloriously zany ‘Sheep’, which opens

Sheep wearing short pink diner uniforms, serving coffee, startling easily. Sheep being followed through evening streets, sensing danger, flocking helplessly. Sheep afraid in the nightclub chaos, hooves on the table, staring blankly.and which ends

Sheep driving with a shotgun on the empty seat, their own dogs for protection, as the new life kicks.the pamphlet’s note – ‘This is a retelling of The Terminator, the female protagonist having been replaced by a flock of sheep.’ – is essential. Would anyone guess? Williams is one who brings a lightness and zest to her notes, a skill which transfers to poems such as ‘There Is an Epigraph’, a found poem of five epigraphs – and one which faces the opening epigraph of the sixth section, ‘We all go a little mad sometimes. words from Norman Bates in Psycho. The levels of play and intertextuality in this collection are an adult mind-game but never with cleverness merely for its own sake. At its heart is a continuing examination of how we engage with the world – or worlds – we live in, how we ‘bear’ our lives. Reality has new dimensions and takes place as much on screens as in the tangible world. In ‘The Burning of the Houses’, the real (the London riots of August 2011) meets the working environment of screens, tweets, links, Facebooking, and videos of kittens. The boundaries between the real and the created are blurring (as with the ‘fake night’ in ‘The Invisible Bear’) as the first four lines show:

Online linking is another way of surviving the horror on the streets; friends help you through, even when they have done nothing to put out the flames.

It is a strength of this collection that it has taken so many of the poems from Williams’ pamphlet (thirteen out of the twenty it contains) and lets their themes grow into a book-length set. Each reading finds new connections – the mark of a book that will survive.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2017 0 • Tags: books, D A Prince, poetry