John Lucas reflects on Michael Wilding’s account of the lives and work of three significant figures from Australia’s early literary history

Wild Bleak Bohemia:

Marcus Clarke, Adam Lindsay Gordon & Henry Kendall – a Documentary

Michael Wilding

Australia Scholarly Publishing Pty Ltd, 2014

ISBN: 9781925003802

$39.95 pb.

Wild Bleak Bohemia:

Marcus Clarke, Adam Lindsay Gordon & Henry Kendall – a Documentary

Michael Wilding

Australia Scholarly Publishing Pty Ltd, 2014

ISBN: 9781925003802

$39.95 pb.

“Only the wasteful virtues earn the sun,” Yeats grandly declared in the Dedicatory Verses to his great collection, Responsibilities. By wasteful virtues he had in mind a grand indifference to cost-counting, a readiness to act according to non-prudential values, and this behaviour – this expression of reckless individuality – was, Yeats claimed, epitomised by an uncle of his who leapt “after a ragged hat in Biscay Bay.” Reading about the three heroes of Michael Wilding’s meticulously detailed “Documentary” I was forcibly reminded of Yeats’s words, as of his later dismissal of the poetry of James Reeves, when he was shown it by Robert Graves. Graves was pressing for his friend’s work to be included in Yeats’s Oxford Book of Twentieth-Century Verse, but Yeats was having none of it. Altogether too reasonable, he thought Reeves. “We poets should be gay, warty lads.”

Marcus Clarke (1846-1881) wasn’t a poet, though the novel by which he is remembered, for His Natural Life, concerning life in the especially brutal Tasmanian Penal Settlement certainly passes the test for wartiness. As to the poets Adam Lindsay Gordon (1833-1870) and Henry Kendall (1839-1882), they were both indifferent to notions of constraint. I suspect that their names and reputations, once bright enough to merit attention this side of the world as well as in Australia, have more or less faded from view, although Wilding notes that Gordon’s quatrain

Life is mostly froth and bubble,

Two things stand like stone,

Kindness in another’s trouble,

Courage in your own

was quoted by “Queen Elizabeth II … in her Christmas message in 1992, her ‘annus horribilis’” , and, he adds, it was also quoted by Princess Diana at a fund-raising event for breast cancer held in Washington D.C. Diana went so far as to reveal it was her favourite poem, though I doubt she had a large selection to choose from. Kingsley Amis’s parody of the lines runs:

Life is mainly grief and labour,

Two things get you through.

Chortling when it hits your neighbour,

Whingeing when it’s you.

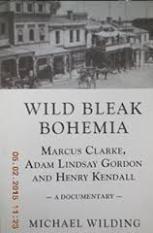

In the invaluable Oxford Literary History of Australia (1998), edited by the late Bruce Bennett, attempts are made to provide judicious critical assessments of the three authors Wilding writes about. Rather more subtly, he takes for granted their importance, not so much for what they wrote but for how they were willy-nilly instrumental in establishing the possibility and circumstances of a literary presence and its identity in nineteenth-century Australian life as that presence developed, more or less ab initio. Hence, his book’s title – the significance of which is enhanced by the cover image, a photograph of “The Argus Office, 76 Collins Street East, Melbourne, 1867.” The Argus was an important newspaper, which gave employment to all three writers, but though you see in the background a substantial three-storey building where the newspaper was housed, your eye is in fact drawn to the wide street in front of it, with its higgledy-piggledy arrangements of horse-drawn carts and drays, looking for all the world like something out of a Hollywood western. Beyond the Argus buildings are others, all somehow provisional, as though they belong to a film set and could at any moment be knocked down. Wild Bleak Bohemia indeed.

A Prefatory Note tells us that “For a brief fourteen months [in1867-1868] the three great originals of Australian writing … were together in Melbourne. Fellow members of the Yorick club, they lived the Bohemian life. ‘The mornings were spent in scribbling, the afternoons in tobacco, the evenings in dinner, theatre and gaslight. I fear we did not lead virtuous lives,’ Marcus Clarke recalled.” Wilding’s book takes us through these eighteen months but also gives us detailed accounts of the lives of the three both before and after these months. In addition, he provides a narrative of the social circumstances which made their “scribbling” possible. Himself a distinguished novelist, Wilding brings a kind of Balzacian thoroughness to a document which, despite its length, never loses narrative pace. This is made possible by his decision not to break the narrative into chapters but to advance it through a series of episodic sections, some very short, others substantial, which between them provide a densely-textured sense of how life for Australians progressed in the middle years of the nineteenth-century, how newspapers, journals, clubs – some but by no means all intended exclusively for writers – generated between them the atmosphere in which writers could draw breath.

Clarke and Gordon were both from upper-class English families. They had a good deal of the insouciance of the “gentleman” and both, arriving in Australia as very young men, brought with them airs and graces that might have seemed calculated to offend the hard-bitten men and women they came among. Yet both were well-liked. Tall poppies they may have been but they were also “characters.” Clarke was positively debonair in his readiness to use his fluent pen as a correspondence clerk in the Bank of Australasia, although his letters, which he dashed off with an easy grace, were not at all what the bank’s manager, or their recipients, wanted, and before long Clarke was shown the door. But his fluent pen was put at the disposal of newspapers, he became for a while a theatre critic, and found himself involved with the life of literary journalism, a mode of existence he did much to shape. Writing to Cyril Hopkins (with whom, as with Cyril’s brother Gerard Manley Hopkins) Clarke had been at school in England, he told him that “I was fond of art and literature; I came where both are unknown.” Something of an exaggeration, perhaps, but it does serve to show the extent to which, like Gordon and Kendall, Clarke had not only to make his way as a writer but to help forge the conditions out of which the life of a writer might become possible.

Once in Australia Clarke learnt to be a good horseman. Gordon did not have to wait that long. Even before he left England, he seems to have been preoccupied to the point of obsession with horse-flesh and riding. Given that he was unusually tall and very short sighted this made for difficulties he never overcame. If Clarke’s qualities and disposition make for a combination of Dickens’s Dick Swiveller and Steerforth, Gordon comes across more as Rawden Crawley in the guise of Crowe Ransom’s Captain Carpenter. Wilding itemises Gordon’s many tumbles, most of them brought on by his inability to detect obstacles in his horse’s path, some of them serious enough to suggest that only by a miracle did he avoid killing himself in a fall. In fact he ended his own life by putting a bullet through his brain when he couldn’t pay for the publication of Bush Ballads, the collection which made his posthumous reputation. A sad end to an often sad life, during which Gordon spent a short while as a member of South Australia’s parliament, had to suffer the death of an adored infant daughter, and allowed a considerable inheritance slip through his fingers, much of it given away to spongers.

Clarke survived for longer but rarely had any money in his pocket. In 1868 he purchased a journal, The Colonial Monthly, which more or less beggared him, and neither the serial publication of His Natural Life, (1872), Australia’s first really important novel, nor its revised book version, called For The Term of His Natural Life, when it was published two years later, did much to alleviate an impecuniousness made worse by his drinking habits.

As for Kendall, who unlike the others was born in Australia to parents with little by way of social position or money, he was a poet of real promise – some would say of accomplishment – who as a young man achieved success with periodical publication in England, where his work was enthusiastically noticed, as well as in his native country. His first collection, Poems and Songs, published in 1862 and as was the custom paid for out of his own pocket, made a considerable stir. One commentator reckoned Kendall’s work to be “national in the sense of being evolved as it were from the country he inhabits.” But the drink got to him (he seems to have inherited his mother’s alcoholism), and his life, as with the lives of Clarke and Gordon, came to a premature, impoverished end.

Bleak indeed. Wild certainly. At all events, untameable. But Bohemian? Well, yes. The O.E.D. dates the term to the mid-19th century: “A socially unconventional person, esp. an artist or writer, of free-and-easy habits, manners, and sometimes morals.” One of the most fascination aspects of Wilding’s important study is the way he shows how early bohemianism emerges in colonial Australia. Yeats was to some extent formed by his experience of the writers and artists with whom he became familiar during the 1890s. “The Decadence” set the tone for much he endorsed and later championed, if critically. Having outlived the period and, as he said, clambered down from his high bar stool, he could take the measure of fin-de-siecle Bohemianism: the Rhymers’ Club, the Cheshire Cheese pub, Henry Harland’s Yellow Book, drink, drugs, madness, the many early deaths. (Dowson, Johnson, “who loved his learning better than mankind,” Beardsley, Wilde….) But three decades earlier, in Melbourne, another form of Bohemianism had come into existence, one even more significant for Australian culture than the Rhymers’ Club was for its English counterpart. The writers whose lives Wilding documents were instrumental in creating and then living, and dying, by the wasteful virtues of wild, bleak Bohemia. Exemplary Bohemians, in fact.

John Lucas reflects on Michael Wilding’s account of the lives and work of three significant figures from Australia’s early literary history

“Only the wasteful virtues earn the sun,” Yeats grandly declared in the Dedicatory Verses to his great collection, Responsibilities. By wasteful virtues he had in mind a grand indifference to cost-counting, a readiness to act according to non-prudential values, and this behaviour – this expression of reckless individuality – was, Yeats claimed, epitomised by an uncle of his who leapt “after a ragged hat in Biscay Bay.” Reading about the three heroes of Michael Wilding’s meticulously detailed “Documentary” I was forcibly reminded of Yeats’s words, as of his later dismissal of the poetry of James Reeves, when he was shown it by Robert Graves. Graves was pressing for his friend’s work to be included in Yeats’s Oxford Book of Twentieth-Century Verse, but Yeats was having none of it. Altogether too reasonable, he thought Reeves. “We poets should be gay, warty lads.”

Marcus Clarke (1846-1881) wasn’t a poet, though the novel by which he is remembered, for His Natural Life, concerning life in the especially brutal Tasmanian Penal Settlement certainly passes the test for wartiness. As to the poets Adam Lindsay Gordon (1833-1870) and Henry Kendall (1839-1882), they were both indifferent to notions of constraint. I suspect that their names and reputations, once bright enough to merit attention this side of the world as well as in Australia, have more or less faded from view, although Wilding notes that Gordon’s quatrain

was quoted by “Queen Elizabeth II … in her Christmas message in 1992, her ‘annus horribilis’” , and, he adds, it was also quoted by Princess Diana at a fund-raising event for breast cancer held in Washington D.C. Diana went so far as to reveal it was her favourite poem, though I doubt she had a large selection to choose from. Kingsley Amis’s parody of the lines runs:

In the invaluable Oxford Literary History of Australia (1998), edited by the late Bruce Bennett, attempts are made to provide judicious critical assessments of the three authors Wilding writes about. Rather more subtly, he takes for granted their importance, not so much for what they wrote but for how they were willy-nilly instrumental in establishing the possibility and circumstances of a literary presence and its identity in nineteenth-century Australian life as that presence developed, more or less ab initio. Hence, his book’s title – the significance of which is enhanced by the cover image, a photograph of “The Argus Office, 76 Collins Street East, Melbourne, 1867.” The Argus was an important newspaper, which gave employment to all three writers, but though you see in the background a substantial three-storey building where the newspaper was housed, your eye is in fact drawn to the wide street in front of it, with its higgledy-piggledy arrangements of horse-drawn carts and drays, looking for all the world like something out of a Hollywood western. Beyond the Argus buildings are others, all somehow provisional, as though they belong to a film set and could at any moment be knocked down. Wild Bleak Bohemia indeed.

A Prefatory Note tells us that “For a brief fourteen months [in1867-1868] the three great originals of Australian writing … were together in Melbourne. Fellow members of the Yorick club, they lived the Bohemian life. ‘The mornings were spent in scribbling, the afternoons in tobacco, the evenings in dinner, theatre and gaslight. I fear we did not lead virtuous lives,’ Marcus Clarke recalled.” Wilding’s book takes us through these eighteen months but also gives us detailed accounts of the lives of the three both before and after these months. In addition, he provides a narrative of the social circumstances which made their “scribbling” possible. Himself a distinguished novelist, Wilding brings a kind of Balzacian thoroughness to a document which, despite its length, never loses narrative pace. This is made possible by his decision not to break the narrative into chapters but to advance it through a series of episodic sections, some very short, others substantial, which between them provide a densely-textured sense of how life for Australians progressed in the middle years of the nineteenth-century, how newspapers, journals, clubs – some but by no means all intended exclusively for writers – generated between them the atmosphere in which writers could draw breath.

Clarke and Gordon were both from upper-class English families. They had a good deal of the insouciance of the “gentleman” and both, arriving in Australia as very young men, brought with them airs and graces that might have seemed calculated to offend the hard-bitten men and women they came among. Yet both were well-liked. Tall poppies they may have been but they were also “characters.” Clarke was positively debonair in his readiness to use his fluent pen as a correspondence clerk in the Bank of Australasia, although his letters, which he dashed off with an easy grace, were not at all what the bank’s manager, or their recipients, wanted, and before long Clarke was shown the door. But his fluent pen was put at the disposal of newspapers, he became for a while a theatre critic, and found himself involved with the life of literary journalism, a mode of existence he did much to shape. Writing to Cyril Hopkins (with whom, as with Cyril’s brother Gerard Manley Hopkins) Clarke had been at school in England, he told him that “I was fond of art and literature; I came where both are unknown.” Something of an exaggeration, perhaps, but it does serve to show the extent to which, like Gordon and Kendall, Clarke had not only to make his way as a writer but to help forge the conditions out of which the life of a writer might become possible.

Once in Australia Clarke learnt to be a good horseman. Gordon did not have to wait that long. Even before he left England, he seems to have been preoccupied to the point of obsession with horse-flesh and riding. Given that he was unusually tall and very short sighted this made for difficulties he never overcame. If Clarke’s qualities and disposition make for a combination of Dickens’s Dick Swiveller and Steerforth, Gordon comes across more as Rawden Crawley in the guise of Crowe Ransom’s Captain Carpenter. Wilding itemises Gordon’s many tumbles, most of them brought on by his inability to detect obstacles in his horse’s path, some of them serious enough to suggest that only by a miracle did he avoid killing himself in a fall. In fact he ended his own life by putting a bullet through his brain when he couldn’t pay for the publication of Bush Ballads, the collection which made his posthumous reputation. A sad end to an often sad life, during which Gordon spent a short while as a member of South Australia’s parliament, had to suffer the death of an adored infant daughter, and allowed a considerable inheritance slip through his fingers, much of it given away to spongers.

Clarke survived for longer but rarely had any money in his pocket. In 1868 he purchased a journal, The Colonial Monthly, which more or less beggared him, and neither the serial publication of His Natural Life, (1872), Australia’s first really important novel, nor its revised book version, called For The Term of His Natural Life, when it was published two years later, did much to alleviate an impecuniousness made worse by his drinking habits.

As for Kendall, who unlike the others was born in Australia to parents with little by way of social position or money, he was a poet of real promise – some would say of accomplishment – who as a young man achieved success with periodical publication in England, where his work was enthusiastically noticed, as well as in his native country. His first collection, Poems and Songs, published in 1862 and as was the custom paid for out of his own pocket, made a considerable stir. One commentator reckoned Kendall’s work to be “national in the sense of being evolved as it were from the country he inhabits.” But the drink got to him (he seems to have inherited his mother’s alcoholism), and his life, as with the lives of Clarke and Gordon, came to a premature, impoverished end.

Bleak indeed. Wild certainly. At all events, untameable. But Bohemian? Well, yes. The O.E.D. dates the term to the mid-19th century: “A socially unconventional person, esp. an artist or writer, of free-and-easy habits, manners, and sometimes morals.” One of the most fascination aspects of Wilding’s important study is the way he shows how early bohemianism emerges in colonial Australia. Yeats was to some extent formed by his experience of the writers and artists with whom he became familiar during the 1890s. “The Decadence” set the tone for much he endorsed and later championed, if critically. Having outlived the period and, as he said, clambered down from his high bar stool, he could take the measure of fin-de-siecle Bohemianism: the Rhymers’ Club, the Cheshire Cheese pub, Henry Harland’s Yellow Book, drink, drugs, madness, the many early deaths. (Dowson, Johnson, “who loved his learning better than mankind,” Beardsley, Wilde….) But three decades earlier, in Melbourne, another form of Bohemianism had come into existence, one even more significant for Australian culture than the Rhymers’ Club was for its English counterpart. The writers whose lives Wilding documents were instrumental in creating and then living, and dying, by the wasteful virtues of wild, bleak Bohemia. Exemplary Bohemians, in fact.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • authors, books, literature, year 2016 0 • Tags: authors, books, John Lucas, literature