Emma Lee admires Deborah Tyler-Bennett’s perceptive handling of memory and nostalgia.

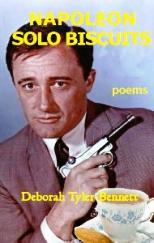

Napoleon Solo Biscuits

Deborah Tyler-Bennett

The King's England Press, www.kingsengland.com

ISBN 978109548257

74pp £7.95

Napoleon Solo Biscuits

Deborah Tyler-Bennett

The King's England Press, www.kingsengland.com

ISBN 978109548257

74pp £7.95

These poems vibrantly bring their subjects to life. Deborah Tyler-Bennett’s skill lies in creating a portrait in words so that even readers who don’t know the subject can still conjure up an empathetic picture and gain an understanding of who the subject is. She moves from personal to researched biographies with ease. In ‘Leaving Zanzibar’, she responds to a TV historian’s comment suggesting that middle classes lives were somehow mourned more than working class ones:

I'd like to know who weighed grief, deciding whose

keener, greater loss meaning youths

bright in stained glass or school-prayer,

more mourned on honours-boards

than those whose names rested, bronze-

plaques on best-parlour walls.

The poem ends by pointing out that those middle class boys,

marched with lads from pit-head, factory gate,

big-house garden, to flounder in blood and clay.

Boys home, no matter if from Pantiles... Sunnydene...

Studio-shots above bronze-discs record

nineteen... twenty... Grinning at bluebirds, before

farmers' fields made hell, a million miles from Zanzibar.

Tyler-Bennett draws focus back onto the tragic loss of so many young lives, regardless of background. The allusion to Vera Lynn’s song (bluebirds aren’t native to the UK), acts as a reminder of the spirit of optimism, the ‘it’ll all be over by Christmas’ attitude, towards the initial outbreak of the First World War. The assonance in hell and million hints at the scale of loss, underlining the complacency of that TV historian.

The book’s title poem looks back to a childhood hobby of collecting cards from biscuit packs. The cards slotted together to create the faces of the two main characters – Napoleon Solo, played by Robert Vaughan, and Ilya Kuryakin, played by David McCallum – from the TV series The Man from U.N.C.L.E:

Who'd finish Napoleon? Graceful

gun-hand, tailoring's edge, but void

in Robert Vaughan's lower face.

Liquorice lashes skimming

jazzy Formica lurking below.

Nostalgia and Co's

dreamt items. Solo's

completion, never-to-be-retro

haunting, easy as 1.2.3.

shiny maroon wrappers spooking

car-park, once school lavatory.

If met, imagine Robert Vaughan'd be

mouth-less, tender eyes (pure gigolo)

slender suit darkening competing class-

rooms, eternity's slick spy shadow.

The odd contrast between suave, sophisticated spy and ordinary packs of biscuits isn’t explored.

Even in nostalgia, Tyler-Bennett avoids hagiography. The poems towards the end of the book turn their focus to more famous lives but refuse to be seduced by the apparent glamour of celebrity. In ‘No Blue Plaque for Johnnie’ Johnnie is the photographer John Deakin (1912-1972) who lived his final days at the Old Ship Hotel in Brighton:

Final bender, shoved below the bed

with boxes of unsorted photographs.

Maid he phoned for tea, finding him dead,

sobbed. He could've shown, unfiltered lenses laugh

at dressed-up lives... fresh shirt's stain,

scarf's rumple, new tie worn askew...

Chilling as sudden holiday rain

awaited visitor, smoke-suited, caught in view-

finders, featured for a subject he'd once known,

but soon put by. Another image stowed under the bed,

but unfound after. 'Dying alone?

Deakin's last dirty trick' as Bacon said.

Deborah Tyler-Bennett relishes a larger-than-life personality and an opportunity to show off her dexterity with vocabulary – which is here tamed by rhyme but is more usually tamed by keeping her subjects in focus and describing their lives as they themselves might have done. Her use of rhythm and enjambment keep the poem moving forward so it feels like a shiny, glittering ornament; but there is always substance and purpose below the decorative surface.

.

Emma Lee‘s most recent publication is Ghosts in the Desert (Indigo Dreams) and she blogs at http://emmalee1.wordpress.com

Emma Lee admires Deborah Tyler-Bennett’s perceptive handling of memory and nostalgia.

These poems vibrantly bring their subjects to life. Deborah Tyler-Bennett’s skill lies in creating a portrait in words so that even readers who don’t know the subject can still conjure up an empathetic picture and gain an understanding of who the subject is. She moves from personal to researched biographies with ease. In ‘Leaving Zanzibar’, she responds to a TV historian’s comment suggesting that middle classes lives were somehow mourned more than working class ones:

The poem ends by pointing out that those middle class boys,

Tyler-Bennett draws focus back onto the tragic loss of so many young lives, regardless of background. The allusion to Vera Lynn’s song (bluebirds aren’t native to the UK), acts as a reminder of the spirit of optimism, the ‘it’ll all be over by Christmas’ attitude, towards the initial outbreak of the First World War. The assonance in hell and million hints at the scale of loss, underlining the complacency of that TV historian.

The book’s title poem looks back to a childhood hobby of collecting cards from biscuit packs. The cards slotted together to create the faces of the two main characters – Napoleon Solo, played by Robert Vaughan, and Ilya Kuryakin, played by David McCallum – from the TV series The Man from U.N.C.L.E:

The odd contrast between suave, sophisticated spy and ordinary packs of biscuits isn’t explored.

Even in nostalgia, Tyler-Bennett avoids hagiography. The poems towards the end of the book turn their focus to more famous lives but refuse to be seduced by the apparent glamour of celebrity. In ‘No Blue Plaque for Johnnie’ Johnnie is the photographer John Deakin (1912-1972) who lived his final days at the Old Ship Hotel in Brighton:

Deborah Tyler-Bennett relishes a larger-than-life personality and an opportunity to show off her dexterity with vocabulary – which is here tamed by rhyme but is more usually tamed by keeping her subjects in focus and describing their lives as they themselves might have done. Her use of rhythm and enjambment keep the poem moving forward so it feels like a shiny, glittering ornament; but there is always substance and purpose below the decorative surface.

.

Emma Lee‘s most recent publication is Ghosts in the Desert (Indigo Dreams) and she blogs at http://emmalee1.wordpress.com

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2016 1 • Tags: books, poetry