Merryn Williams is good at finding poetry in the highs and lows of human affairs

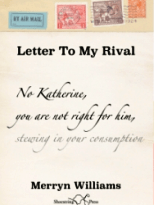

Letter to my Rival

Merryn Williams

Shoestring Press

ISBN 978-1-910323-39-7

49 pp £10

Letter to my Rival

Merryn Williams

Shoestring Press

ISBN 978-1-910323-39-7

49 pp £10

The poems in Letter to my Rival are largely focussed upon people. We eavesdrop on conversations and correspondence as well as private thoughts and memories. Sometimes we are given a perceptive commentary on a whole life or a major incident within it. All of this – at least from the point of view of this reader – is a Good Thing since I find human relationships, imaginings and misunderstandings to be fruitful ground for poems to spring from.

It is perhaps revealing that I have just drawn upon a cliché from Sellar & Yeatman’s classic 1066 And All That because their division of the whole of British history into Good and Bad Things has a kind of clarity which is shared by Williams’ poetry. This is not, of course, to say that her poems are naive or simplistic; but they do have a directness and accessibility which, for the most part, make the reader feel included.

The subjects of the poems range from somewhat generic types, such as actors or politicians, through friends and family of the author and on to specific famous people. We meet a chess grandmaster in the collection’s opening poem and we soon learn that his life is not a particularly settled one:

Countless, those rooms

where you’ve put down your head;

Gideon Bible

ashtray and bed.

Nor is it one which offers peace of mind:

Get up, gulp down

your roughly cooked meals;

meet the young rival

who snaps at your heels.

Rivalry of another kind occurs in the particularly effective poem ‘A.N.Other’ in which a moderately successful actor (but some people said I was good) is doing a piece to camera as part of a televised tribute to a major theatrical star. Williams cleverly lets resentment ooze from beneath the surface of joking recollections of being young hopefuls together: We went out drinking quite a lot, and I’ve seen him under circumstances – / but invariably he pulled himself together before the curtain. And after token agreement about a tragic loss to the British theatre comes a judicious drip of vitriol but I wonder if, in another ten years, he’ll be quite so –.

That note of envy in the presence of celebrity occurs again, somewhat nearer to home, in ‘At the Literary Festival’ where, when invited to share a platform with a famous writer, you’re far too busy chatting up the great man … whose name is blazoned in red letters and ambition urges you to lick his spittle, sip your Chardonnay; his audience yours for a fraction of a day.

‘The First Woman’ is a particularly intriguing quasi-generic poem which names no names but invites us to speculate on various candidates of whom it might be said

She could have had an honourable place

in record books. She was the very first.

We cheered her, but it ended in disgrace.

There is more tenderness in the poems which are (or which appear to be) more personal. ‘Villanelle of Sorrow ‘ begins on a note of gentle resignation – Keep calm. He would be ninety-one years old / if he were here, and that you know can’t be – which is well sustained throughout the poem. The fancies and fantasies of the bereaved are delicately exposed in ‘Missing Person’

There was no trace, no suicide note, no body,

but there were sightings...

... you can’t know, and you keep on wondering.

His mother sticks up notices in the subway,

the picture ages underneath your eyes.

On the dark underside of the bridge you glimpse them

white streaks, peeling away.

Similarly self-aware clutching at the past is well captured in ‘Do not Disturb’ as we listen to the thoughts of someone who wants to ring you up, tell you (my lips just moving ) / the family news; but knows that to do so means suspending disbelief:

Although the real phone’s dead

and someone else has got your number, I can

still activate the line inside my head.

These poems have a ring of truth. Other, darker, pieces may be fictional but have the vividness of well-shot film. A betrayed woman still in her flimsy dress … drives wildly through a black unknown landscape. Another woman worries about possible violence in her friend’s marriage: I asked her to stay the night… But she went and a few hours later is in hospital. All I know is, she was all right when she left me.

It is only when we come to the poems which deal with real-life characters that the collection loses some of its accessibility because of a tacit, and possibly optimistic, assumption that readers will ‘get’ all the references. The book’s title poem is, evidently, based on an episode in the life of writer Katherine Mansfield – but I only know this from introductory remarks made by Williams at a reading. It may not matter greatly if a reader is unaware of the background to this poem since it is in any case powerful enough as an expression of jealousy of one woman for another: No, Katherine, you are not right for him, stewing / in your consumption. He will be / a great man, and you are far off, sourly-smelling / of disinfectant. Other poems such as ‘Charlotte Mew’ and ‘Gissing’s Streets’ do clearly identify their subjects; but it would surely have done no harm to provide brief notes to explain the specific incidents which are alluded to. And I did feel a particular lack of information to accompany the poem entitled ‘2006’ which seems to expect me to grasp some recent historical significance behind the (undoubtedly dramatic) lines

Which child, born this dark month, will leave a heavier

footprint than ours? The babes all look the same.

Perhaps these last few comments are minor quibbles about an otherwise very enjoyable collection. As can be seen in the quoted extracts, Williams makes a lot of use of rhyme and form and does so skilfully but with a light touch. She also gives us three entertaining versions of poems by Horace and a couple of translations from the French of Baudelaire and Louis Aragon. At just 49 pages, this collection is not a long one: but it is not short of variety.

.

Michael Bartholomew-Biggs

Merryn Williams is good at finding poetry in the highs and lows of human affairs

The poems in Letter to my Rival are largely focussed upon people. We eavesdrop on conversations and correspondence as well as private thoughts and memories. Sometimes we are given a perceptive commentary on a whole life or a major incident within it. All of this – at least from the point of view of this reader – is a Good Thing since I find human relationships, imaginings and misunderstandings to be fruitful ground for poems to spring from.

It is perhaps revealing that I have just drawn upon a cliché from Sellar & Yeatman’s classic 1066 And All That because their division of the whole of British history into Good and Bad Things has a kind of clarity which is shared by Williams’ poetry. This is not, of course, to say that her poems are naive or simplistic; but they do have a directness and accessibility which, for the most part, make the reader feel included.

The subjects of the poems range from somewhat generic types, such as actors or politicians, through friends and family of the author and on to specific famous people. We meet a chess grandmaster in the collection’s opening poem and we soon learn that his life is not a particularly settled one:

Nor is it one which offers peace of mind:

Rivalry of another kind occurs in the particularly effective poem ‘A.N.Other’ in which a moderately successful actor (but some people said I was good) is doing a piece to camera as part of a televised tribute to a major theatrical star. Williams cleverly lets resentment ooze from beneath the surface of joking recollections of being young hopefuls together: We went out drinking quite a lot, and I’ve seen him under circumstances – / but invariably he pulled himself together before the curtain. And after token agreement about a tragic loss to the British theatre comes a judicious drip of vitriol but I wonder if, in another ten years, he’ll be quite so –.

That note of envy in the presence of celebrity occurs again, somewhat nearer to home, in ‘At the Literary Festival’ where, when invited to share a platform with a famous writer, you’re far too busy chatting up the great man … whose name is blazoned in red letters and ambition urges you to lick his spittle, sip your Chardonnay; his audience yours for a fraction of a day.

‘The First Woman’ is a particularly intriguing quasi-generic poem which names no names but invites us to speculate on various candidates of whom it might be said

There is more tenderness in the poems which are (or which appear to be) more personal. ‘Villanelle of Sorrow ‘ begins on a note of gentle resignation – Keep calm. He would be ninety-one years old / if he were here, and that you know can’t be – which is well sustained throughout the poem. The fancies and fantasies of the bereaved are delicately exposed in ‘Missing Person’

Similarly self-aware clutching at the past is well captured in ‘Do not Disturb’ as we listen to the thoughts of someone who wants to ring you up, tell you (my lips just moving ) / the family news; but knows that to do so means suspending disbelief:

These poems have a ring of truth. Other, darker, pieces may be fictional but have the vividness of well-shot film. A betrayed woman still in her flimsy dress … drives wildly through a black unknown landscape. Another woman worries about possible violence in her friend’s marriage: I asked her to stay the night… But she went and a few hours later is in hospital. All I know is, she was all right when she left me.

It is only when we come to the poems which deal with real-life characters that the collection loses some of its accessibility because of a tacit, and possibly optimistic, assumption that readers will ‘get’ all the references. The book’s title poem is, evidently, based on an episode in the life of writer Katherine Mansfield – but I only know this from introductory remarks made by Williams at a reading. It may not matter greatly if a reader is unaware of the background to this poem since it is in any case powerful enough as an expression of jealousy of one woman for another: No, Katherine, you are not right for him, stewing / in your consumption. He will be / a great man, and you are far off, sourly-smelling / of disinfectant. Other poems such as ‘Charlotte Mew’ and ‘Gissing’s Streets’ do clearly identify their subjects; but it would surely have done no harm to provide brief notes to explain the specific incidents which are alluded to. And I did feel a particular lack of information to accompany the poem entitled ‘2006’ which seems to expect me to grasp some recent historical significance behind the (undoubtedly dramatic) lines

Perhaps these last few comments are minor quibbles about an otherwise very enjoyable collection. As can be seen in the quoted extracts, Williams makes a lot of use of rhyme and form and does so skilfully but with a light touch. She also gives us three entertaining versions of poems by Horace and a couple of translations from the French of Baudelaire and Louis Aragon. At just 49 pages, this collection is not a long one: but it is not short of variety.

.

Michael Bartholomew-Biggs

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2015 0 • Tags: poetry