Thomas Ovans reviews two new poetry anthologies from two small presses which tackle big themes.

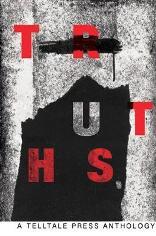

Truths

Edited by Sarah Barnsley, Robin Houghton & Peter Kenny

Telltale Press

ISBN 978 0 9928555 5 0

£8

Truths

Edited by Sarah Barnsley, Robin Houghton & Peter Kenny

Telltale Press

ISBN 978 0 9928555 5 0

£8

Towards the Light - Poems of reconciliation

Edited by Vivien Whelpton

Kapaju Books

ISBN 978 1 5272199 3 9

£8

Towards the Light - Poems of reconciliation

Edited by Vivien Whelpton

Kapaju Books

ISBN 978 1 5272199 3 9

£8

Interestingly these two anthologies share the property of being quite locally based productions. The publishers of Truths, along with many of the contributors, have strong Sussex connections while Towards the Light chiefly features writers from Essex and Suffolk, and is part of a larger project, run by members of the Poetry Wivenhoe group, which marks the hundredth anniversary of World War 1. The term ‘local’, however, in no way implies any weakness in production quality or in content. In fact it may not be over-fanciful discern a coherence and unity in these volumes that stems from the fact that the editors and many of the poets are well-known to each other.

Truths invited its contributors to explore ‘truths’ in any way they wished, bearing in mind this is an age in which “the idea of truth is besieged” and “‘the truth may be indistinguishable from ‘alternative facts.” This sounds like a pretty broad remit and the contributors have responded to it in many interesting ways. As always, a reviewer can only give examples and apologise to those poets whose work goes unmentioned.

Marion Tracy’s poem ’The Heart’ that opens the anthology confronts us with a truth which is often unspoken because of its intimate nature: “both of you, husband and child, have passed / into and out of my body.” And within the next few pages we meet other truths which are often unspoken because they are shocking. Louise Tondeur’s prose poem is set in a post-natal ward and quotes – who knows how reliably – a young mother of a very premature baby who claims the maternity ward policy is “500g anything under that and they don’t, you know, they leave it don’t do nothing.” Clare Best’s ‘You ask’ takes us to a grimmer place, the witness room for an execution – “victim’s people to the right, inmate’s people to the left. No they never meet …” – and saves till last the mention of

the cries of the mothers. Those mothers

are like wild animals. Sounds you wouldn’t think

a human could make.

Louise Tondeur’s poem about babies that are allowed to fade away is cleverly paired with another about children that never were. Katrina Naomi tells her unborn daughter the truth that “I’m sorry I wasn’t prepared / to have her occupy my body.” Another kind of search for / avoidance of the truths among the “might-bes” and “might-have-beens” occurs in Sue Rose’s ‘Going Dark’ about a woman in whose mind “neurons are winking out”. Nevertheless

Still she smiles

as if she lives in a lucid world,

and we play down, play along, in a game

that is no joke ....

Fortunately not all the poems deal with such dark truths. Jeremy Page writes amusingly of Mrs Clout, a neighbour of his grandma, who declared her certainties

That no good would come of it.

That it was an ill wind.

What a stitch in time would save.

What fine words wouldn’t butter.

Sarah Barnsley, on the other hand, throws both accepted truth and caution to the winds. In ‘I prefer to get my information from unreliable sources (online version)’ she says

Bananas to peer-reviewed articles from journals we subscribe to!

Knickers to traceable footnotes (correctly-punctuated)!

What I want is catastrophic personal testimony

delivered to my inbox at 1.35 in the morning ...

In the extracts quoted so far, the truths considered, believed or rejected are fairly plain. But the complex and elusive nature of truth is well captured in a second poem by Sue Rose ‘Self-Portrait on Pavement’ in which perception of one’s actual self is limited to “an outline / of an unknowable creature / blocking its own light” or a “grounded shadow” whose arms are “stumps of umbrage” (a phrase as wonderful as it is incomprehensible!). Abegail Morley’s ‘The Promotion of Forgetting’ responds to its epigraph “If he cannot silence her absolutely, he makes sure no one listens” with some even more enigmatic but verbally dense and satisfying lines:

I’m stuck-shut, know his watch face

holds mine in its mock-gilt grin, tells me I’m sick

with the spirit of the dead. ...

... I can tug a whole fish bone from my throat

as a party-piece if I want. I’m surprised by someone

who holds my gullet shut, with just one clench.

There is of course much more in this book – thirty-four poems by twenty-five poets, to be precise – and the three editors, Sarah Barnsley, Robin Houghton & Peter Kenny, have done a fine job of assembly and arrangement. It deserves a place on any poetry-lover’s shelf.

*

Towards the Light is a companion volume to so too have the doves gone which was published in 2014 and used the theme ‘Conflict’ to mark the centenary of the start of World War 1. (A review is at https://londongrip.co.uk/2014/03/poetry-review-spring-2014-so-too-have-the-doves-gone/). Towards the Light commemorates the end of that “war to end war” and its theme is ‘Reconciliation’. Naturally many of the poems relate to war and its aftermath. But others deal with the equally important and equally difficult matter of reconciliation between individuals and within families and wider society.

The book begins where we might expect with a reminder of the desolation of the battlefields. M W Bewick urges himself to “forgive the mud its slow increase and sticking depths” and then allows his vision to expand so that perhaps we are not (only) talking about war

let me forget to forget and see you still

here catching the briars that might bring tomorrow’s flowers

Caroline Gill’s acrostic poem ‘Et in terra pax’ recalls the strange and temporary reconciliation that was the 1914 Christmas truce. It begins

Christmas came down to us in the trenches, pouring

Happiness into our hearts ...

Subsequent poems consider the home front where families and friends try to come to terms with the losses of loved ones. Michael Bartholomew-Biggs imagines those who resort to séances for consolation:

I didn’t suffer – tell them that. Maud wonders

can she trust the promise from a medium

in this shabby half-full village hall?

Judith Wolton recounts a more tangible attempt at reconciliation as descendants of WW1 soldiers from England and Germany meet on an old battlefield and exchange photographs and memories:

“My father wrote such love to my mother.

He was gassed, came home an invalid –

I remember his slippers.”

‘Finishing sentences’ by Stephen Boyce is the first poem to move wholly to the private and personal. A separation has occurred but eventually the protagonists find a way to give back “the best of ourselves”. Once released

... words come tumbling

and we’re finishing ... each other’s sentence.

Other poets also tell stories of mending broken relationships. Eliza Kentridge is very specific in ‘Spring, 1975’. “I shouted at my grandfather / Just the once but it was bad enough / Our own six-day war.” Joan Norlev Taylor seeks to overcome the belated, and seldom expressed, realisation that

we have harmed ourselves more

in the battle, so that

now – more than then –

we have cause to fight...

There are some clever metaphors for the process of reconciliation. Sheena Clover likens it to dressing a wound until “a fragile scar… / became a puckered flag, a symbol of truce.” More unexpectedly, Julia Brady draws a comparison with composting. You have to

give it time.

If the weather tames it and the worms turn it,

it may yet reconcile itself to loosening its grip

and transubstantiate into nutrients

for something more elegant.

Brady’s poem also warns us to give the word reconciliation its true weight and not confuse it with the easy patching-up that serves for minor disagreements. Compost, she tells us

is not the same article as leaf-mould,

which disintegrates of its own accord,

sifting through the filigree of its own skeletons

Mending the harm done by war is, however, the theme to which the poems keep returning. Sometimes there is healing simply in being able to say what actually happened. Adrian May imagines the re-telling of stories through a recurring dream

Every night and every night

Like soldiers now and then

We dream the dream that comes to make

Or end their suffering.

Nancy Mattson writes of two Finnish brothers returning from war who go to the sauna with a bottle of whisky and tell each other once – and once only – the horrors they have seen.

We will tell our stories in water on hot stones,

the steam that releases memories we can bear

to reveal only to each other...

...

Mother of all steam, heal us, take away the stench.

Sometimes of course war stories too confusing to be told clearly, as in Pamela Job’s haunting ‘Promised Land’

yes we have forgotten who we are dressed in rags

who sold us off so cheap our fathers

their fathers perhaps who will never know

The foregoing quotes do no more than give a flavour of the anthology but they demonstrate both the range and the quality of the best writing in Towards the Light. But one feature that has not yet been mentioned is the presence of French, German or Italian versions of several of the poems. I do wonder how many readers will fully appreciate them (but perhaps I am merely signalling my own linguistic limitations!). Nevertheless, the inclusion of these translations is of obvious symbolic significance in a book which is largely concerned with celebrating the healing of European wounds.

One small reservation is the fact that there are no notes on contributors. There are several poets in this anthology who are unfamiliar to me and about whom I would have liked to know more. But this is a relatively small quibble about a very worthwhile, well-edited and well produced anthology.

May 9 2018

Truths & Reconciliation

Thomas Ovans reviews two new poetry anthologies from two small presses which tackle big themes.

Interestingly these two anthologies share the property of being quite locally based productions. The publishers of Truths, along with many of the contributors, have strong Sussex connections while Towards the Light chiefly features writers from Essex and Suffolk, and is part of a larger project, run by members of the Poetry Wivenhoe group, which marks the hundredth anniversary of World War 1. The term ‘local’, however, in no way implies any weakness in production quality or in content. In fact it may not be over-fanciful discern a coherence and unity in these volumes that stems from the fact that the editors and many of the poets are well-known to each other.

Truths invited its contributors to explore ‘truths’ in any way they wished, bearing in mind this is an age in which “the idea of truth is besieged” and “‘the truth may be indistinguishable from ‘alternative facts.” This sounds like a pretty broad remit and the contributors have responded to it in many interesting ways. As always, a reviewer can only give examples and apologise to those poets whose work goes unmentioned.

Marion Tracy’s poem ’The Heart’ that opens the anthology confronts us with a truth which is often unspoken because of its intimate nature: “both of you, husband and child, have passed / into and out of my body.” And within the next few pages we meet other truths which are often unspoken because they are shocking. Louise Tondeur’s prose poem is set in a post-natal ward and quotes – who knows how reliably – a young mother of a very premature baby who claims the maternity ward policy is “500g anything under that and they don’t, you know, they leave it don’t do nothing.” Clare Best’s ‘You ask’ takes us to a grimmer place, the witness room for an execution – “victim’s people to the right, inmate’s people to the left. No they never meet …” – and saves till last the mention of

Louise Tondeur’s poem about babies that are allowed to fade away is cleverly paired with another about children that never were. Katrina Naomi tells her unborn daughter the truth that “I’m sorry I wasn’t prepared / to have her occupy my body.” Another kind of search for / avoidance of the truths among the “might-bes” and “might-have-beens” occurs in Sue Rose’s ‘Going Dark’ about a woman in whose mind “neurons are winking out”. Nevertheless

Fortunately not all the poems deal with such dark truths. Jeremy Page writes amusingly of Mrs Clout, a neighbour of his grandma, who declared her certainties

Sarah Barnsley, on the other hand, throws both accepted truth and caution to the winds. In ‘I prefer to get my information from unreliable sources (online version)’ she says

In the extracts quoted so far, the truths considered, believed or rejected are fairly plain. But the complex and elusive nature of truth is well captured in a second poem by Sue Rose ‘Self-Portrait on Pavement’ in which perception of one’s actual self is limited to “an outline / of an unknowable creature / blocking its own light” or a “grounded shadow” whose arms are “stumps of umbrage” (a phrase as wonderful as it is incomprehensible!). Abegail Morley’s ‘The Promotion of Forgetting’ responds to its epigraph “If he cannot silence her absolutely, he makes sure no one listens” with some even more enigmatic but verbally dense and satisfying lines:

There is of course much more in this book – thirty-four poems by twenty-five poets, to be precise – and the three editors, Sarah Barnsley, Robin Houghton & Peter Kenny, have done a fine job of assembly and arrangement. It deserves a place on any poetry-lover’s shelf.

*

Towards the Light is a companion volume to so too have the doves gone which was published in 2014 and used the theme ‘Conflict’ to mark the centenary of the start of World War 1. (A review is at https://londongrip.co.uk/2014/03/poetry-review-spring-2014-so-too-have-the-doves-gone/). Towards the Light commemorates the end of that “war to end war” and its theme is ‘Reconciliation’. Naturally many of the poems relate to war and its aftermath. But others deal with the equally important and equally difficult matter of reconciliation between individuals and within families and wider society.

The book begins where we might expect with a reminder of the desolation of the battlefields. M W Bewick urges himself to “forgive the mud its slow increase and sticking depths” and then allows his vision to expand so that perhaps we are not (only) talking about war

Caroline Gill’s acrostic poem ‘Et in terra pax’ recalls the strange and temporary reconciliation that was the 1914 Christmas truce. It begins

Subsequent poems consider the home front where families and friends try to come to terms with the losses of loved ones. Michael Bartholomew-Biggs imagines those who resort to séances for consolation:

Judith Wolton recounts a more tangible attempt at reconciliation as descendants of WW1 soldiers from England and Germany meet on an old battlefield and exchange photographs and memories:

‘Finishing sentences’ by Stephen Boyce is the first poem to move wholly to the private and personal. A separation has occurred but eventually the protagonists find a way to give back “the best of ourselves”. Once released

Other poets also tell stories of mending broken relationships. Eliza Kentridge is very specific in ‘Spring, 1975’. “I shouted at my grandfather / Just the once but it was bad enough / Our own six-day war.” Joan Norlev Taylor seeks to overcome the belated, and seldom expressed, realisation that

There are some clever metaphors for the process of reconciliation. Sheena Clover likens it to dressing a wound until “a fragile scar… / became a puckered flag, a symbol of truce.” More unexpectedly, Julia Brady draws a comparison with composting. You have to

Brady’s poem also warns us to give the word reconciliation its true weight and not confuse it with the easy patching-up that serves for minor disagreements. Compost, she tells us

Mending the harm done by war is, however, the theme to which the poems keep returning. Sometimes there is healing simply in being able to say what actually happened. Adrian May imagines the re-telling of stories through a recurring dream

Every night and every night Like soldiers now and then We dream the dream that comes to make Or end their suffering.Nancy Mattson writes of two Finnish brothers returning from war who go to the sauna with a bottle of whisky and tell each other once – and once only – the horrors they have seen.

Sometimes of course war stories too confusing to be told clearly, as in Pamela Job’s haunting ‘Promised Land’

The foregoing quotes do no more than give a flavour of the anthology but they demonstrate both the range and the quality of the best writing in Towards the Light. But one feature that has not yet been mentioned is the presence of French, German or Italian versions of several of the poems. I do wonder how many readers will fully appreciate them (but perhaps I am merely signalling my own linguistic limitations!). Nevertheless, the inclusion of these translations is of obvious symbolic significance in a book which is largely concerned with celebrating the healing of European wounds.

One small reservation is the fact that there are no notes on contributors. There are several poets in this anthology who are unfamiliar to me and about whom I would have liked to know more. But this is a relatively small quibble about a very worthwhile, well-edited and well produced anthology.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2018 0 • Tags: books, poetry, Thomas Ovans