John Lucas praises the craft and authenticity in a new novel by Robert Edric – and regrets that this accomplished writer doesn’t have the larger reputation he deserves

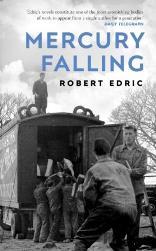

Mercury Falling

Robert Edric

Transworld/Penguin, 2018

£16.99

Mercury Falling

Robert Edric

Transworld/Penguin, 2018

£16.99

In the early 1970s I knew a man called Hedgehog Bill. Not his real name of course, but the soubriquet which he was given by drinkers in the back street pub which I then frequented and where he was a regular. The rumour was that he had no home of his own and spent most nights sleeping out, often under a hedge, which, given his unkempt appearance and dress, was probably true. He claimed to be an expert at repairing cars, though other regulars of the Royal Oak were not so sure. ‘I wouldn’t trust him with a kiddy’s go-cart,’ one told me. ‘Give him your car to mend and you know what? He’ll drive it around for a week or so looking for any work he can come by – private taxi, ferrying small goods – kip in it, then hand it back and snap your hand off for his money. Cash, no cheques. He’ll swear blind he’s worked all the hours God gives to fix whatever was wrong, but he won’t have touched the bogger.’

A friend of mine, a lecturer at Nottingham University, who also used the pub, took Bill’s side against his detractors. His professor was in need of expert advice on the defective braking system of an old sports car he’d recently acquired. ‘I’ve got Bill to look the car over for him,’ my friend said airily, ‘he knows what he’s talking about.’ His misplaced confidence nearly cost the professor his life when, speeding down the M1, he came to a road block, slammed on his brakes, there was no response, and the poor man was saved from death only by expert use of steering wheel and clutching system more usually associated with Brand’s Hatch. Even so, he ploughed into a stationary lorry and the car was a write-off. Hedgehog Bill went missing for several weeks after that. When he returned to the pub all he said was ‘car seemed alright when I give it him back.’

Reading Robert Edric’s new novel I was again and again reminded of Bill. Mercury Falling is set in fenland country in 1954. The date matters, because the previous year there had been serious, even catastrophic flooding over parts of Eastern England, and although the novel avoids clunky detailing of this, the sense of dank earth, of half-ruined buildings, of mould and decrepitude is superbly evoked. So is the sense of the fens’ wide, flat, featureless landscapes. These are landscapes where a man or building can be seen from miles away, although distances are uncertain. ‘All around him boundaries were lost and the sea, land and sky were confused in a shimmer of heat haze.’ In an earlier novel, Peacetime (2002), Edric made good use of such landscapes and that novel, too, was set in early post-war England, where people are scrabbling to live among the rubble, as it feels, of war. The events of Peacetime are seen through the observing eye of an outsider who, sent to supervise the demolition of gun emplacements set up against the threat of German invasion, encounters the kind of local community first written about by George Crabbe. Crabbe, the great poet of un-picturesque, rural circumstance, has his narrator of The Village report with a kind of sour relish on how locals, ‘scowl at strangers with suspicious eye.’

There is no such reporter in Mercury Falling. The story, which is, as it were, told directly, concentrates on a year in the life of its hapless protagonist, Jimmy Devlin, and his attempts to survive on whatever work comes his way in this bleak, inhospitable environment.

Hapless may, though, be the wrong work. The novel is in two halves: Summer and Winter. The lowering temperature, the mercury falling in the glass, suggests a worsening of times and the running down and out of luck for a man who at best is not much more than a drifter. But Mercury is also, of course, the Roman god associated with thievery, deceit, cunning. He is the begetter of Autolycus, that merry, amoral, wandering rogue, although Devlin is not really merry. In his unreflective determination to put up with whatever happens to him, which includes a large measure of self-pity, and to take advantage of whatever bit of luck comes his way, he is more suggestive of that earlier Shakesperian rogue, Parolles. ‘Simply the thing I am/Shall make me live.’

The novel opens with Devlin, still abed in mid-morning, being knocked up by a bailiff. Skelton, as the bailiff is called, has instructions to throw Devlin out of the abandoned, rotten farmhouse where he has been living for months without paying the rent he’d agreed on with the owner. (We’ll later discover that the owner has plans to flatten the building, which is in unrentable condition.) Devlin puts up a pathetic show of belligerance, contemptuously knocked away by the bailiff: ‘the law,’ Skelton says, ‘is always on the side of money and them what has it and them what’s owed it.’ Devlin grabs a rabbit gun and fires it at the bailiff, nicking him in the arm. The action, stupidly ineffectual though it is, will come back to haunt him.

In fact, it is integral to this beautifully crafted novel that, picaresque thought it may at first seem, as Devlin wanders from place to place, always on the wrong side of the law, he can’t escape from those he wrongs or anyway falls foul of. Sooner or later they catch up with him. The miles of thinly-populated fens may put distance between people but there aren’t sufficient of them to ensure anonymity. Rumours reach everywhere. Devlin may not have seen his own father for years, for example, but from time to time someone will feed the son a snippet of information about the man who disappeared from his life when he was a boy. Rumours of Devlin’s own fecklessness certainly come to the ear of his sister, who has through marriage achieved some sort of penny-pinching, joyless respectability. There is a superbly managed scene where he goes to see her in her small house:

He knocked on the door and stood back.

His sister unlocked the door, opened it a few inches and looked out at him.

‘Hello,’ Devlin said.

‘What is it this time,’ Ellen said.

‘Can’t a man visit his own family? You’re getting very suspicious in your old age.’ She was

thirty, a year older than Devlin.’

‘“ Family”? We’re only ever that when it suits.’ She looked along the road behind him. Morris

didn’t appreciate her having visitors when he wasn’t present.

Morris is Ellen’s husband, a man who, someone whispers to Devlin at his sister’s wedding had ‘something of the Yid about him. It was something Devlin was happy to believe.’

There’s not much to be said in favour of Devlin. But then that’s true of most of the people he encounters. He inhabits a world of petty crooks, fenland spivvery, where there’s no honour among thieves. Like him, most of the younger men claim to have ‘done their bit’ during the war, which in his case turns out to have been time in Colchester military prison when, as a reluctant conscript, he tried selling red petrol to a garage owner and was ‘Caught, charged, found guilty, imprisoned, all in the space of a week.’ (Red petrol had been coloured to prevent its use for civilian purposes.) Like Hedgehog Bill, Devlin claims to be able to mend car and lorry engines. He tells this to the foreman of a gang of men he’s working with, draining a dyke, and the man laughs at him. ‘“you and a million others, chum, you and a million others,”’ the foreman says.

The man who remembers seeing Devlin in prison is Ray Duggan, the unashamed champion of ‘looking after Number One’. Duggan is an intriguingly imagined hard man, in whose flood-damaged house Devlin becomes for a while a lodger and by whom he’s recruited to help out on nights when Duggan goes off in his lorry to steal anything that, word has it, is available. He has no compunction about lifting whatever he can, whether it’s Government paid-for machinery dumped by the roadside preparatory for use in draining flooded fields and dykes, or sacks of shellfish waiting to be collected by the fishermen who’ve patiently garnered them from river and inlet. Everyone, Duggan implies, is at it, but his reputation as a hard man ensures that he gets what he wants and sells to whom he chooses.

Looking after Number One is the novel’s leitmotif. A young Borstal escapee tells Devlin that it’s the best way to be. ‘Look after yourself and nobody else, that’s my motto.’ And when by chance Devlin later meets the wife of the bailiff Skelton who threw him out, she tells him ‘Hardship and misfortune? You don’t know the meaning of the words. Self, self, self – that’s all it is with people like you.’

The first part of the novel covers the summer months when Devlin finds seasonal work and even a woman, the sister of two gypsies he falls in with after Duggan has thrown him out. They are fairground workers – gaffs (though Edric doesn’t use the term) – and they offer Devlin shelter in a rotten caravan, for which he pays by helping them with their night work. He goes so far as to lead them to a cache of stolen goods he’s earlier helped Duggan thieve, and the twinge of emotion he feels when he does so ’less of conscience than fear that Duggan will guess who tipped ‘the gyppos’ off and will sooner or later come looking for him.

But then winter arrives – Edric evokes the look of the wintry landscape in a number of terse, exactly judged paragraphs – and work drops off. Mercury is falling. In the novel’s second part Devlin’s fortunes take several turns for the worse and as they do so he spins increasingly out of control. He trashes Skelton’s house, he sets fire to the gypsies’ caravan after they’ve turfed him out, and then, in a kind of grim pastiche of some Hollywood Western, he makes his way to Duggan’s broken-down house, armed with a shotgun he found in the course of wrecking Skelton’s place.

I’m not going to reveal what happens then, nor how the novel ends. I will, though, say that Mercury Falling is written with the practised, unshowy, telling economy of a very good novelist. As with his previous novel, Field Service, a minor masterpiece set in Northern France immediately after the end of the First World War where an English Army Officer is supervising the re-burial of soldiers killed in battle, Mercury Falling, while occupied with very different people, evokes an atmosphere of emotional exhaustion, deadened expectations, or, if the word isn’t too grand, accidie. But whereas in Field Service people for the most part struggle to do their duty, in Mercury Falling the only duty is to looking after yourself, which, in the case of Devlin’s sister, becomes a tepid, mind-numbing dream of betterment – ownership of a TV and washing machine, of trying to ‘maintain appearances,’ of not letting yourself go. It’s something I can remember only too clearly from the 1950s. In fact, Edric provides insights into that decade sharper, more telling than most social historians. When Devlin turns up at his sister’s in clothes he’s stolen from Skelton’s house, she says with some amazement, ‘You look alright, I’ll give you that,’ And Devlin, seeking to persuade her he’s now found work and can be thought of as a respectable member of society, says, ‘This old rubbish? You should see me on Sundays.’ Sundays, still the day of rest in the 1950s, was also the one day of the week when working men and women could, and did, dress up. (In contrast, middle-class men, freed of the requirements of office wear, of suits and ties, and polished shoes, dressed down.)

Mercury Falling has any number of such moments. This may suggest that the novel is a kind of dour, latter-day Gissing. (Although Gissing is far better than most accounts of him would suggest.) But Edric is far too good a novelist to be content with drab reportage. His novels are a long way from plain cooking made still plainer by plain cooks. Although both his eye and ear for how people look, how they talk, how they behave, how they live are enviably good, he is also a masterly contriver of narrative, and he invariably gets onto really interesting subjects, or anyway subjects he makes interesting. It is something of a scandal that so good a novelist shouldn’t have a larger reputation. Yes, he has, quite rightly, won prizes, including the James Tait Prize, the W.H.Smith Literary Award, he has been twice long-listed for the Booker, and short-listed for the Dublin Impac Prize. But he isn’t, as they say, fashionable, which translates into ‘not from Bloomsbury, Hampstead,’ and, as the late, great Roy Fisher used to remark, ‘a few spots round that way.’ There is, after all, a world elsewhere.

May 11 2018

Mercury Falling

John Lucas praises the craft and authenticity in a new novel by Robert Edric – and regrets that this accomplished writer doesn’t have the larger reputation he deserves

In the early 1970s I knew a man called Hedgehog Bill. Not his real name of course, but the soubriquet which he was given by drinkers in the back street pub which I then frequented and where he was a regular. The rumour was that he had no home of his own and spent most nights sleeping out, often under a hedge, which, given his unkempt appearance and dress, was probably true. He claimed to be an expert at repairing cars, though other regulars of the Royal Oak were not so sure. ‘I wouldn’t trust him with a kiddy’s go-cart,’ one told me. ‘Give him your car to mend and you know what? He’ll drive it around for a week or so looking for any work he can come by – private taxi, ferrying small goods – kip in it, then hand it back and snap your hand off for his money. Cash, no cheques. He’ll swear blind he’s worked all the hours God gives to fix whatever was wrong, but he won’t have touched the bogger.’

A friend of mine, a lecturer at Nottingham University, who also used the pub, took Bill’s side against his detractors. His professor was in need of expert advice on the defective braking system of an old sports car he’d recently acquired. ‘I’ve got Bill to look the car over for him,’ my friend said airily, ‘he knows what he’s talking about.’ His misplaced confidence nearly cost the professor his life when, speeding down the M1, he came to a road block, slammed on his brakes, there was no response, and the poor man was saved from death only by expert use of steering wheel and clutching system more usually associated with Brand’s Hatch. Even so, he ploughed into a stationary lorry and the car was a write-off. Hedgehog Bill went missing for several weeks after that. When he returned to the pub all he said was ‘car seemed alright when I give it him back.’

Reading Robert Edric’s new novel I was again and again reminded of Bill. Mercury Falling is set in fenland country in 1954. The date matters, because the previous year there had been serious, even catastrophic flooding over parts of Eastern England, and although the novel avoids clunky detailing of this, the sense of dank earth, of half-ruined buildings, of mould and decrepitude is superbly evoked. So is the sense of the fens’ wide, flat, featureless landscapes. These are landscapes where a man or building can be seen from miles away, although distances are uncertain. ‘All around him boundaries were lost and the sea, land and sky were confused in a shimmer of heat haze.’ In an earlier novel, Peacetime (2002), Edric made good use of such landscapes and that novel, too, was set in early post-war England, where people are scrabbling to live among the rubble, as it feels, of war. The events of Peacetime are seen through the observing eye of an outsider who, sent to supervise the demolition of gun emplacements set up against the threat of German invasion, encounters the kind of local community first written about by George Crabbe. Crabbe, the great poet of un-picturesque, rural circumstance, has his narrator of The Village report with a kind of sour relish on how locals, ‘scowl at strangers with suspicious eye.’

There is no such reporter in Mercury Falling. The story, which is, as it were, told directly, concentrates on a year in the life of its hapless protagonist, Jimmy Devlin, and his attempts to survive on whatever work comes his way in this bleak, inhospitable environment.

Hapless may, though, be the wrong work. The novel is in two halves: Summer and Winter. The lowering temperature, the mercury falling in the glass, suggests a worsening of times and the running down and out of luck for a man who at best is not much more than a drifter. But Mercury is also, of course, the Roman god associated with thievery, deceit, cunning. He is the begetter of Autolycus, that merry, amoral, wandering rogue, although Devlin is not really merry. In his unreflective determination to put up with whatever happens to him, which includes a large measure of self-pity, and to take advantage of whatever bit of luck comes his way, he is more suggestive of that earlier Shakesperian rogue, Parolles. ‘Simply the thing I am/Shall make me live.’

The novel opens with Devlin, still abed in mid-morning, being knocked up by a bailiff. Skelton, as the bailiff is called, has instructions to throw Devlin out of the abandoned, rotten farmhouse where he has been living for months without paying the rent he’d agreed on with the owner. (We’ll later discover that the owner has plans to flatten the building, which is in unrentable condition.) Devlin puts up a pathetic show of belligerance, contemptuously knocked away by the bailiff: ‘the law,’ Skelton says, ‘is always on the side of money and them what has it and them what’s owed it.’ Devlin grabs a rabbit gun and fires it at the bailiff, nicking him in the arm. The action, stupidly ineffectual though it is, will come back to haunt him.

In fact, it is integral to this beautifully crafted novel that, picaresque thought it may at first seem, as Devlin wanders from place to place, always on the wrong side of the law, he can’t escape from those he wrongs or anyway falls foul of. Sooner or later they catch up with him. The miles of thinly-populated fens may put distance between people but there aren’t sufficient of them to ensure anonymity. Rumours reach everywhere. Devlin may not have seen his own father for years, for example, but from time to time someone will feed the son a snippet of information about the man who disappeared from his life when he was a boy. Rumours of Devlin’s own fecklessness certainly come to the ear of his sister, who has through marriage achieved some sort of penny-pinching, joyless respectability. There is a superbly managed scene where he goes to see her in her small house:

He knocked on the door and stood back. His sister unlocked the door, opened it a few inches and looked out at him. ‘Hello,’ Devlin said. ‘What is it this time,’ Ellen said. ‘Can’t a man visit his own family? You’re getting very suspicious in your old age.’ She was thirty, a year older than Devlin.’ ‘“ Family”? We’re only ever that when it suits.’ She looked along the road behind him. Morris didn’t appreciate her having visitors when he wasn’t present.Morris is Ellen’s husband, a man who, someone whispers to Devlin at his sister’s wedding had ‘something of the Yid about him. It was something Devlin was happy to believe.’

There’s not much to be said in favour of Devlin. But then that’s true of most of the people he encounters. He inhabits a world of petty crooks, fenland spivvery, where there’s no honour among thieves. Like him, most of the younger men claim to have ‘done their bit’ during the war, which in his case turns out to have been time in Colchester military prison when, as a reluctant conscript, he tried selling red petrol to a garage owner and was ‘Caught, charged, found guilty, imprisoned, all in the space of a week.’ (Red petrol had been coloured to prevent its use for civilian purposes.) Like Hedgehog Bill, Devlin claims to be able to mend car and lorry engines. He tells this to the foreman of a gang of men he’s working with, draining a dyke, and the man laughs at him. ‘“you and a million others, chum, you and a million others,”’ the foreman says.

The man who remembers seeing Devlin in prison is Ray Duggan, the unashamed champion of ‘looking after Number One’. Duggan is an intriguingly imagined hard man, in whose flood-damaged house Devlin becomes for a while a lodger and by whom he’s recruited to help out on nights when Duggan goes off in his lorry to steal anything that, word has it, is available. He has no compunction about lifting whatever he can, whether it’s Government paid-for machinery dumped by the roadside preparatory for use in draining flooded fields and dykes, or sacks of shellfish waiting to be collected by the fishermen who’ve patiently garnered them from river and inlet. Everyone, Duggan implies, is at it, but his reputation as a hard man ensures that he gets what he wants and sells to whom he chooses.

Looking after Number One is the novel’s leitmotif. A young Borstal escapee tells Devlin that it’s the best way to be. ‘Look after yourself and nobody else, that’s my motto.’ And when by chance Devlin later meets the wife of the bailiff Skelton who threw him out, she tells him ‘Hardship and misfortune? You don’t know the meaning of the words. Self, self, self – that’s all it is with people like you.’

The first part of the novel covers the summer months when Devlin finds seasonal work and even a woman, the sister of two gypsies he falls in with after Duggan has thrown him out. They are fairground workers – gaffs (though Edric doesn’t use the term) – and they offer Devlin shelter in a rotten caravan, for which he pays by helping them with their night work. He goes so far as to lead them to a cache of stolen goods he’s earlier helped Duggan thieve, and the twinge of emotion he feels when he does so ’less of conscience than fear that Duggan will guess who tipped ‘the gyppos’ off and will sooner or later come looking for him.

But then winter arrives – Edric evokes the look of the wintry landscape in a number of terse, exactly judged paragraphs – and work drops off. Mercury is falling. In the novel’s second part Devlin’s fortunes take several turns for the worse and as they do so he spins increasingly out of control. He trashes Skelton’s house, he sets fire to the gypsies’ caravan after they’ve turfed him out, and then, in a kind of grim pastiche of some Hollywood Western, he makes his way to Duggan’s broken-down house, armed with a shotgun he found in the course of wrecking Skelton’s place.

I’m not going to reveal what happens then, nor how the novel ends. I will, though, say that Mercury Falling is written with the practised, unshowy, telling economy of a very good novelist. As with his previous novel, Field Service, a minor masterpiece set in Northern France immediately after the end of the First World War where an English Army Officer is supervising the re-burial of soldiers killed in battle, Mercury Falling, while occupied with very different people, evokes an atmosphere of emotional exhaustion, deadened expectations, or, if the word isn’t too grand, accidie. But whereas in Field Service people for the most part struggle to do their duty, in Mercury Falling the only duty is to looking after yourself, which, in the case of Devlin’s sister, becomes a tepid, mind-numbing dream of betterment – ownership of a TV and washing machine, of trying to ‘maintain appearances,’ of not letting yourself go. It’s something I can remember only too clearly from the 1950s. In fact, Edric provides insights into that decade sharper, more telling than most social historians. When Devlin turns up at his sister’s in clothes he’s stolen from Skelton’s house, she says with some amazement, ‘You look alright, I’ll give you that,’ And Devlin, seeking to persuade her he’s now found work and can be thought of as a respectable member of society, says, ‘This old rubbish? You should see me on Sundays.’ Sundays, still the day of rest in the 1950s, was also the one day of the week when working men and women could, and did, dress up. (In contrast, middle-class men, freed of the requirements of office wear, of suits and ties, and polished shoes, dressed down.)

Mercury Falling has any number of such moments. This may suggest that the novel is a kind of dour, latter-day Gissing. (Although Gissing is far better than most accounts of him would suggest.) But Edric is far too good a novelist to be content with drab reportage. His novels are a long way from plain cooking made still plainer by plain cooks. Although both his eye and ear for how people look, how they talk, how they behave, how they live are enviably good, he is also a masterly contriver of narrative, and he invariably gets onto really interesting subjects, or anyway subjects he makes interesting. It is something of a scandal that so good a novelist shouldn’t have a larger reputation. Yes, he has, quite rightly, won prizes, including the James Tait Prize, the W.H.Smith Literary Award, he has been twice long-listed for the Booker, and short-listed for the Dublin Impac Prize. But he isn’t, as they say, fashionable, which translates into ‘not from Bloomsbury, Hampstead,’ and, as the late, great Roy Fisher used to remark, ‘a few spots round that way.’ There is, after all, a world elsewhere.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, year 2018 0 • Tags: books, John Lucas