Carla Scarano visits two exhibitions in Florence: The return to Italy of Salvatore Ferragamo in 1927 and the Dawn of a Nation after WW II

1927, The return to Italy. Salvatore Ferragamo and the Twentieth-century visual culture

Museo Salvatore Ferragamo. Palazzo Spini Feroni, Florence. 19 May 2017-2 May 2018

Dawn of a Nation. From Guttuso to Fontana and Schifano

Palazzo Strozzi, Florence. 16 March-22 July 2018

Two outstanding exhibitions are currently taking place in Florence focusing on Italian identity through visual art, culture and craftsmanship. 1927, The return to Italy. Salvatore Ferragamo and the Twentieth-century visual culture marks the ninetieth anniversary of his return to Italy after twelve years in California, and focuses on the rebirth of Italian culture after the Great War. Dawn of a Nation at Palazzo Strozzi explores art, politics and society from the 1950s till 1968. From different points of view, both exhibitions highlight how Italian identity was rebuilt after the trauma of the two wars in distinctive but equally meaningful ways. The common denominator is the concept of identity and nationhood, stressing the importance of culture and art in the building of a nation.

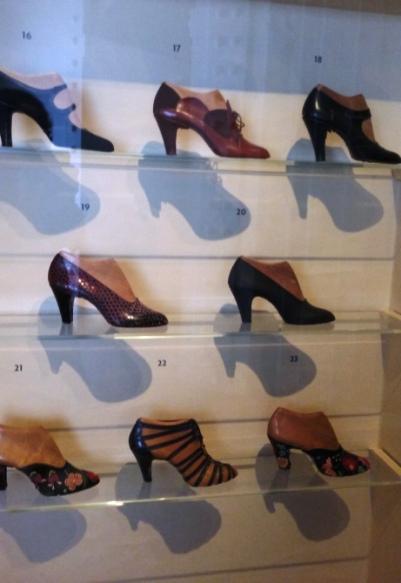

Salvatore Ferragamo was a shoe designer coming from a poor family with fourteen children living in Bonito, a little village in Campania, south of Italy. He started as a shoemaker and owned his own shop when he was only eleven. At seventeen he emigrated to America and settled in California where he became ‘the shoemaker of the stars’ working for Hollywood studios. He wished to create the perfect shoe, not only beautiful and original, but also and above all absolutely comfortable. For this reason he studied the anatomy of the foot in the US and won prizes for his innovative models, like the ‘invisible’ sandals, where the upper part was formed by nylon threads, the cage heel and the wedge shoes.

Salvatore Ferragamo was a shoe designer coming from a poor family with fourteen children living in Bonito, a little village in Campania, south of Italy. He started as a shoemaker and owned his own shop when he was only eleven. At seventeen he emigrated to America and settled in California where he became ‘the shoemaker of the stars’ working for Hollywood studios. He wished to create the perfect shoe, not only beautiful and original, but also and above all absolutely comfortable. For this reason he studied the anatomy of the foot in the US and won prizes for his innovative models, like the ‘invisible’ sandals, where the upper part was formed by nylon threads, the cage heel and the wedge shoes.

The exhibition organized by Carlo Sisi, does not concentrate on Ferragamo’s world only, but aims to be an overview of the 1920s with special attention to visual and decorative arts.

Coming back to Florence in 1927 and opening his factory in this important artistic centre, Ferragamo wanted to stress the geographical and artistic importance of the Tuscan city. In line with the Renaissance tradition, the bottega (workshop) was the place where the artisans were not only makers but creators as well. Within this Italian tradition, the exhibition shows how Ferragamo’s work developed in a cultural thriving context where the emphasis on Italian local craftsmanship was intended to highlight Italian identity.

Italy was a new nation at the time, unified in 1861 under King Vittorio Emanuele II, Rome was finally conquered ten years later, and the last territories in the north east were annexed only after WW I. The concept of national identity was not a secondary topic but a paramount one, and art and culture played an important role in its definition, as is often the case.

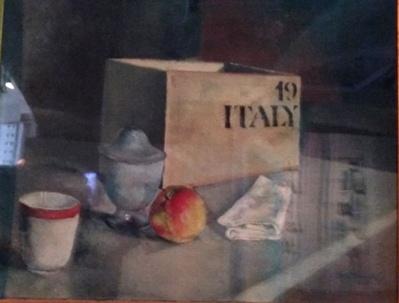

Ferragamo’s voyage in an ocean liner back to Italy is the frame and the metaphor that encapsulates the exhibition, a journey of discovery of a personal and national identification made real by the decor of the rooms. For example, crates labelled ‘Italy’, inspired by the box that Mimo Maccari painted in his ‘Still Life’, are the pedestals of some of the sculptures exhibited; an effective idea that helps to involve the visitor in the journey.

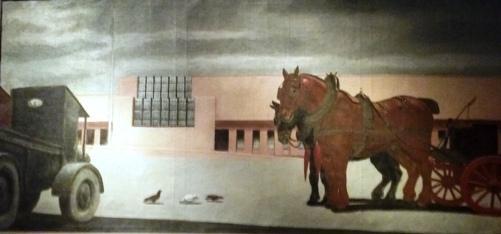

Together with Ferragamo’s historical shoes testifying his mastery and creativity, like mules, boots, pumps, sandals, closed and laced shoes, strap shoes and prototypes, the exhibition also presents folklore and decorative arts: pottery, furniture, ceramics and textiles. The display strikes a balance between innovation and tradition that is symbolized by a painting by John Baldwin, ‘Stazione di Santa Maria Novella’ (1930), where a car is positioned near a cart with horses. Valuing local traditions and regional manufacturing was also a way to promote Italian products in a national effort to keep pace with the other European countries. Italy was certainly economically underdeveloped compared to France, Germany and Britain. Nevertheless, its regional heritage was a source of artistic inspiration that could be combined with new technical inventions. This was supported by the wish to return to order and stability after the devastation of WW I, and also to reaffirm the professional skills that had made Italian products renowned all over the world.

Ferragamo fits perfectly in this social and cultural thriving context. In his factory in Florence he produced over three hundred and fifty pair of shoes a day and employed seven hundred and fifty shoemakers. His shoes were luxury items mainly aimed for export and shipped to rich countries like the US. He managed to merge the technical and scientific skills he had acquired in the US with the Italian craftsmanship, and with his remarkable creativity and exquisite taste.

As visitors can discover in the video room, comfortably sitting on deck chairs soothed by piano melodies and surrounded by projections on three walls, the first Monza Biennale in 1927, an international exposition of decorative arts, was fundamental to promote Italian products both locally and abroad.

The late 1920s were the eve of Fascism that imposed an authoritarian regime and nationalistic politics but also protected Italian goods and aspired to bring Italian technology to the level of the more developed European countries. Considering the Italian economical situation, it was an unrealistic utopian program that ended with the alliance with Nazi Germany and the disaster of WW II.

The exhibition also accentuates the new concept of woman, the importance of sport and the care of the body in the 20s. Nature and sport became paramount thanks both to British influence and to the revival of the Olympic games. Futurism reflected this ethic where ‘the passion for danger, unflinching courage, strength and the agility and spring of the muscles’ indicate the belief in the necessity of order and rationality, discipline and rigour to enable progress and well-being of humanity, a mentality that distorted to excess eventually brought to the atrocities of the second conflict.

Care of the body is clear in Ferragamo’s work as well where the study and measurement of the foot and shoe comfort are central. He not only valued the work of the artisan but also the process of production which he efficiently divided into segments. He also experimented new materials like straw, fish skin and cork, confirming his pioneering approach at all levels.

Shoes were more visible and became an essential important part of the outfit as the hemlines were shorter, encouraging a new vision of woman revealed in à la garçonnes haircuts, in the use of trousers and in simpler more practical dresses. Comfortable elegant shoes were essential to the new active and independent woman in a time when the modern concept of the body was invented. Some items in the exhibition, like the bronze nude by Alimondo Ciampi or the gold wire sculptures by Giacomo Balla, emphasize movement and youth and highlight the importance of sport, dance and beauty centres, new in the 20s and now part of our everyday life.

The exhibition presents and links the different cultural strands proposed in visual arts in the 1920s in the interesting and original frame of the voyage in an ocean liner that culminates in the relaxing video room with soft music, captivating pictures, video clips and comfortable deck chairs. Nevertheless, a technical explanation of Ferragamo’s methods would have enriched this valuable exhibition which only vaguely mentioned the master’s practical approach. The help of some sensory or touchable items, maybe the opportunity to make a shoe with cardboard or practice measuring a foot, a tactile experience, would have helped to understand better the versatility of this remarkable artist and business man.

On the upper floor there is also the opportunity to visit the shop with its astonishing creations, not only woman and man’s footwear but also bags and clothes, which are unfortunately unaffordable for people with an average income.

***

The birth of a sense of nationhood is also the focus of Dawn of a Nation at Palazzo Strozzi, which displays visual art works of outstanding Italian artists between the 50s and late 60s. In this case the concept of identity is explored through experimental methods that also reflect a political commitment in the years after the tragic experience of Fascism and WW II. This is also the period of the ‘economic miracle’ when Italy was radically transformed from a mainly rural to an industrial society. Significantly, in 2018 sees the fiftieth anniversary of the 1968 protest, a year that not only marked a general global revolt but also hoped in a renewal, maybe echoed today in the Italian recent election results.

As in the Ferragamo’s exhibition, but in a contemporary context, art and culture play a main role in developing new ideas and helping to build an Italian identity after WW II as well. In the first room, references to the fight against the oppressor is clear in the big canvas by Renato Guttuso, ‘The Battle of Ponte dell’Ammiraglio’, a battle fought by Garibaldini in 1860 to free Sicily from Bourbons during the Italian Risorgimento, which eventually brought to the unification of Italy. The picture links Garibaldi’s red shirts to the Partigiani of the Resistance who fought against Nazi Germans, a connection that underlines people’s struggle against oppression symbolized by Bourbons and Fascists. The video footage in the same room is a perfect introduction to the exhibition overviewing in about twenty minutes the history of Italy from Risorgimento, to WW I and II, Fascism and the industrial production of the 50s and 60s. The emphasis is on the sense of liberation and confidence of the 60s supported by an incredible economic growth never experienced before in Italy, and culminates in the 1968 protest. Therefore, this sense of rebirth fuelled by the economic boom is ambivalent, on one hand, there is an intensive production of the ‘made in Italy’, like Italian fashion, the FIAT 600 and 500, and the Vespa, on the other hand there is the dispersing, empty reality of consumerism.

Thus, the exhibition points out how the political commitment of these years intended to reshape Italian future. In Turcato’s ‘Political Rally’, the triangular shapes of the red flags testify this intention, as well as in Mimmo Rotella’s ‘The last King of Kings, where a picture of Mussolini’s face is seen through the rips of a shredded poster. It is a symbol of a past that cannot be cancelled completely but is now torn into pieces.

In a comprehensive logical way, each room of the exhibition focuses on a specific group of artists that have a common trend or experimented with similar materials, or worked in the same city and regularly met in clubs, squares or galleries.

The new abstract expressions of Vedova, Fontana and Burri give a sense of the break with the traumatic recent past in an attempt to rebuild a new Italian identity from zero. This is the sense of Burri’s torn sacks, that symbolically show the wounds of the war sewn up by the artist to restore the self; or by the violent strokes of Emilio Vedova’s ‘Clash of Situations’ where the contradictions of the black marks on a blue and white background express the anger and frustration of the artist. Their work was not understood by the media and politicians of the time, it was considered abstruse and too informal in its utter break with Italian past artistic tradition.

A whole room of the exhibition is dedicated to the monochrome white, which is considered a metaphor for freedom, displaying artwork in experimental materials like food, polyvinyl acetate adhesive and foam rubber. They were new materials manufactured in Italy during the economic boom. Therefore, the art work creates sort of alternative products to the commercial ones revealing its opposition to the cost-effectiveness of the industrial products. Besides works of Scarpitta, Savelli, Castellani and Turcato, the most challenging pieces are ‘Artist’s Shit’ by Piero Manzoni and Fontana’s cut canvas, ‘Spatial Concept, Waiting’. They are provocative works that intend to question the commercialization of art connecting it to the organic in Manzoni, and to a fracture in Fontana, considered by the artist a ‘philosophical expression’.

New symbols are communicated by Pistoletto, Gnoli and Pascali who worked in Rome in the 60s when La Dolce Vita, Cinecittà (the ‘Hollywood of the Tiber’) and the VIP lifestyle, captured by paparazzi in via Veneto, absorbed media interest. Artists, instead, look for symbols and signs that simplify reality in an attempt to frame it in timeless images, like Pistoletto’s ‘Lunch Painting’; or else they concentrate on details, like in Gnoli’s hyper-realistic pictures of shirts, collars or beds. They reveal a compulsion to frame, fix and analyse specific features in a world too easily mesmerized by the cinema and the promising economic boom.

The criticism of mass media communication is clear in the attention to technical skills that refer to the Italian craftsmanship tradition in a physical production that is above all a personal involvement with the object. This is evident in the work of Giosetta Fioroni where she fills the outline of a photo taken from a magazine with enamel; it is a homemade product that means to defy some ‘industrial’ work of Pop Art.

Clashes and rallies of 1968 visibly stand out in the red and black pictures by Franco Angeli and Mario Schifano reaffirming the connections with Garibaldi’s red shirts, the Resistenza and the Italian Communist party, PCI. Therefore, the Italian artistic context that emerges from the different strands seems to materialize in the political revolt that aims to turn the traumatic past upside down and question the materialist certainties of the economic boom with intriguing use of new materials and thought-provoking images.

The exhibition has the great merit of displaying relevant meaningful works of some of the most important Italian artists of the period after WW II, highlighting their contribution to Italian art and culture. A clearer final conclusion on how all these different perspectives contributed in a problematic way to compose an Italian identity should have been stated more clearly at the end. Though in the last room the tapestry ‘Maps’ by Alighiero Boetti, which identifies the geographical distinctiveness of each country in its flag and political emblem, seems to allude to an international view rather than a national one, still the exhibition lacks a definite conclusion.

Both exhibitions deal with important periods of Italian history, crucial moments in the development of the sense of a nation and in the building of an Italian identity, where art, both decorative art, craftsmanship and fine art, played a leading role in the making of the Italian nationhood.

Apr 23 2018

In search of an Italian identity

Carla Scarano visits two exhibitions in Florence: The return to Italy of Salvatore Ferragamo in 1927 and the Dawn of a Nation after WW II

1927, The return to Italy. Salvatore Ferragamo and the Twentieth-century visual culture

Museo Salvatore Ferragamo. Palazzo Spini Feroni, Florence. 19 May 2017-2 May 2018

Dawn of a Nation. From Guttuso to Fontana and Schifano

Palazzo Strozzi, Florence. 16 March-22 July 2018

Two outstanding exhibitions are currently taking place in Florence focusing on Italian identity through visual art, culture and craftsmanship. 1927, The return to Italy. Salvatore Ferragamo and the Twentieth-century visual culture marks the ninetieth anniversary of his return to Italy after twelve years in California, and focuses on the rebirth of Italian culture after the Great War. Dawn of a Nation at Palazzo Strozzi explores art, politics and society from the 1950s till 1968. From different points of view, both exhibitions highlight how Italian identity was rebuilt after the trauma of the two wars in distinctive but equally meaningful ways. The common denominator is the concept of identity and nationhood, stressing the importance of culture and art in the building of a nation.

The exhibition organized by Carlo Sisi, does not concentrate on Ferragamo’s world only, but aims to be an overview of the 1920s with special attention to visual and decorative arts.

Coming back to Florence in 1927 and opening his factory in this important artistic centre, Ferragamo wanted to stress the geographical and artistic importance of the Tuscan city. In line with the Renaissance tradition, the bottega (workshop) was the place where the artisans were not only makers but creators as well. Within this Italian tradition, the exhibition shows how Ferragamo’s work developed in a cultural thriving context where the emphasis on Italian local craftsmanship was intended to highlight Italian identity.

Italy was a new nation at the time, unified in 1861 under King Vittorio Emanuele II, Rome was finally conquered ten years later, and the last territories in the north east were annexed only after WW I. The concept of national identity was not a secondary topic but a paramount one, and art and culture played an important role in its definition, as is often the case.

Ferragamo’s voyage in an ocean liner back to Italy is the frame and the metaphor that encapsulates the exhibition, a journey of discovery of a personal and national identification made real by the decor of the rooms. For example, crates labelled ‘Italy’, inspired by the box that Mimo Maccari painted in his ‘Still Life’, are the pedestals of some of the sculptures exhibited; an effective idea that helps to involve the visitor in the journey.

Together with Ferragamo’s historical shoes testifying his mastery and creativity, like mules, boots, pumps, sandals, closed and laced shoes, strap shoes and prototypes, the exhibition also presents folklore and decorative arts: pottery, furniture, ceramics and textiles. The display strikes a balance between innovation and tradition that is symbolized by a painting by John Baldwin, ‘Stazione di Santa Maria Novella’ (1930), where a car is positioned near a cart with horses. Valuing local traditions and regional manufacturing was also a way to promote Italian products in a national effort to keep pace with the other European countries. Italy was certainly economically underdeveloped compared to France, Germany and Britain. Nevertheless, its regional heritage was a source of artistic inspiration that could be combined with new technical inventions. This was supported by the wish to return to order and stability after the devastation of WW I, and also to reaffirm the professional skills that had made Italian products renowned all over the world.

Ferragamo fits perfectly in this social and cultural thriving context. In his factory in Florence he produced over three hundred and fifty pair of shoes a day and employed seven hundred and fifty shoemakers. His shoes were luxury items mainly aimed for export and shipped to rich countries like the US. He managed to merge the technical and scientific skills he had acquired in the US with the Italian craftsmanship, and with his remarkable creativity and exquisite taste.

As visitors can discover in the video room, comfortably sitting on deck chairs soothed by piano melodies and surrounded by projections on three walls, the first Monza Biennale in 1927, an international exposition of decorative arts, was fundamental to promote Italian products both locally and abroad.

The late 1920s were the eve of Fascism that imposed an authoritarian regime and nationalistic politics but also protected Italian goods and aspired to bring Italian technology to the level of the more developed European countries. Considering the Italian economical situation, it was an unrealistic utopian program that ended with the alliance with Nazi Germany and the disaster of WW II.

The exhibition also accentuates the new concept of woman, the importance of sport and the care of the body in the 20s. Nature and sport became paramount thanks both to British influence and to the revival of the Olympic games. Futurism reflected this ethic where ‘the passion for danger, unflinching courage, strength and the agility and spring of the muscles’ indicate the belief in the necessity of order and rationality, discipline and rigour to enable progress and well-being of humanity, a mentality that distorted to excess eventually brought to the atrocities of the second conflict.

Care of the body is clear in Ferragamo’s work as well where the study and measurement of the foot and shoe comfort are central. He not only valued the work of the artisan but also the process of production which he efficiently divided into segments. He also experimented new materials like straw, fish skin and cork, confirming his pioneering approach at all levels.

Shoes were more visible and became an essential important part of the outfit as the hemlines were shorter, encouraging a new vision of woman revealed in à la garçonnes haircuts, in the use of trousers and in simpler more practical dresses. Comfortable elegant shoes were essential to the new active and independent woman in a time when the modern concept of the body was invented. Some items in the exhibition, like the bronze nude by Alimondo Ciampi or the gold wire sculptures by Giacomo Balla, emphasize movement and youth and highlight the importance of sport, dance and beauty centres, new in the 20s and now part of our everyday life.

The exhibition presents and links the different cultural strands proposed in visual arts in the 1920s in the interesting and original frame of the voyage in an ocean liner that culminates in the relaxing video room with soft music, captivating pictures, video clips and comfortable deck chairs. Nevertheless, a technical explanation of Ferragamo’s methods would have enriched this valuable exhibition which only vaguely mentioned the master’s practical approach. The help of some sensory or touchable items, maybe the opportunity to make a shoe with cardboard or practice measuring a foot, a tactile experience, would have helped to understand better the versatility of this remarkable artist and business man.

On the upper floor there is also the opportunity to visit the shop with its astonishing creations, not only woman and man’s footwear but also bags and clothes, which are unfortunately unaffordable for people with an average income.

***

The birth of a sense of nationhood is also the focus of Dawn of a Nation at Palazzo Strozzi, which displays visual art works of outstanding Italian artists between the 50s and late 60s. In this case the concept of identity is explored through experimental methods that also reflect a political commitment in the years after the tragic experience of Fascism and WW II. This is also the period of the ‘economic miracle’ when Italy was radically transformed from a mainly rural to an industrial society. Significantly, in 2018 sees the fiftieth anniversary of the 1968 protest, a year that not only marked a general global revolt but also hoped in a renewal, maybe echoed today in the Italian recent election results.

As in the Ferragamo’s exhibition, but in a contemporary context, art and culture play a main role in developing new ideas and helping to build an Italian identity after WW II as well. In the first room, references to the fight against the oppressor is clear in the big canvas by Renato Guttuso, ‘The Battle of Ponte dell’Ammiraglio’, a battle fought by Garibaldini in 1860 to free Sicily from Bourbons during the Italian Risorgimento, which eventually brought to the unification of Italy. The picture links Garibaldi’s red shirts to the Partigiani of the Resistance who fought against Nazi Germans, a connection that underlines people’s struggle against oppression symbolized by Bourbons and Fascists. The video footage in the same room is a perfect introduction to the exhibition overviewing in about twenty minutes the history of Italy from Risorgimento, to WW I and II, Fascism and the industrial production of the 50s and 60s. The emphasis is on the sense of liberation and confidence of the 60s supported by an incredible economic growth never experienced before in Italy, and culminates in the 1968 protest. Therefore, this sense of rebirth fuelled by the economic boom is ambivalent, on one hand, there is an intensive production of the ‘made in Italy’, like Italian fashion, the FIAT 600 and 500, and the Vespa, on the other hand there is the dispersing, empty reality of consumerism.

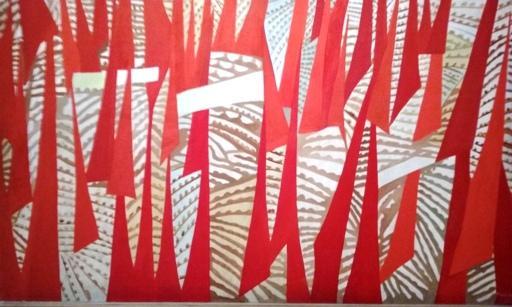

Thus, the exhibition points out how the political commitment of these years intended to reshape Italian future. In Turcato’s ‘Political Rally’, the triangular shapes of the red flags testify this intention, as well as in Mimmo Rotella’s ‘The last King of Kings, where a picture of Mussolini’s face is seen through the rips of a shredded poster. It is a symbol of a past that cannot be cancelled completely but is now torn into pieces.

In a comprehensive logical way, each room of the exhibition focuses on a specific group of artists that have a common trend or experimented with similar materials, or worked in the same city and regularly met in clubs, squares or galleries.

The new abstract expressions of Vedova, Fontana and Burri give a sense of the break with the traumatic recent past in an attempt to rebuild a new Italian identity from zero. This is the sense of Burri’s torn sacks, that symbolically show the wounds of the war sewn up by the artist to restore the self; or by the violent strokes of Emilio Vedova’s ‘Clash of Situations’ where the contradictions of the black marks on a blue and white background express the anger and frustration of the artist. Their work was not understood by the media and politicians of the time, it was considered abstruse and too informal in its utter break with Italian past artistic tradition.

A whole room of the exhibition is dedicated to the monochrome white, which is considered a metaphor for freedom, displaying artwork in experimental materials like food, polyvinyl acetate adhesive and foam rubber. They were new materials manufactured in Italy during the economic boom. Therefore, the art work creates sort of alternative products to the commercial ones revealing its opposition to the cost-effectiveness of the industrial products. Besides works of Scarpitta, Savelli, Castellani and Turcato, the most challenging pieces are ‘Artist’s Shit’ by Piero Manzoni and Fontana’s cut canvas, ‘Spatial Concept, Waiting’. They are provocative works that intend to question the commercialization of art connecting it to the organic in Manzoni, and to a fracture in Fontana, considered by the artist a ‘philosophical expression’.

New symbols are communicated by Pistoletto, Gnoli and Pascali who worked in Rome in the 60s when La Dolce Vita, Cinecittà (the ‘Hollywood of the Tiber’) and the VIP lifestyle, captured by paparazzi in via Veneto, absorbed media interest. Artists, instead, look for symbols and signs that simplify reality in an attempt to frame it in timeless images, like Pistoletto’s ‘Lunch Painting’; or else they concentrate on details, like in Gnoli’s hyper-realistic pictures of shirts, collars or beds. They reveal a compulsion to frame, fix and analyse specific features in a world too easily mesmerized by the cinema and the promising economic boom.

The criticism of mass media communication is clear in the attention to technical skills that refer to the Italian craftsmanship tradition in a physical production that is above all a personal involvement with the object. This is evident in the work of Giosetta Fioroni where she fills the outline of a photo taken from a magazine with enamel; it is a homemade product that means to defy some ‘industrial’ work of Pop Art.

Clashes and rallies of 1968 visibly stand out in the red and black pictures by Franco Angeli and Mario Schifano reaffirming the connections with Garibaldi’s red shirts, the Resistenza and the Italian Communist party, PCI. Therefore, the Italian artistic context that emerges from the different strands seems to materialize in the political revolt that aims to turn the traumatic past upside down and question the materialist certainties of the economic boom with intriguing use of new materials and thought-provoking images.

The exhibition has the great merit of displaying relevant meaningful works of some of the most important Italian artists of the period after WW II, highlighting their contribution to Italian art and culture. A clearer final conclusion on how all these different perspectives contributed in a problematic way to compose an Italian identity should have been stated more clearly at the end. Though in the last room the tapestry ‘Maps’ by Alighiero Boetti, which identifies the geographical distinctiveness of each country in its flag and political emblem, seems to allude to an international view rather than a national one, still the exhibition lacks a definite conclusion.

Both exhibitions deal with important periods of Italian history, crucial moments in the development of the sense of a nation and in the building of an Italian identity, where art, both decorative art, craftsmanship and fine art, played a leading role in the making of the Italian nationhood.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • art, exhibitions, politics, year 2018 0 • Tags: art, Carla Scarano, exhibitions, politics