James Roderick Burns has no doubts about the importance of Mayakovsky’s epic poem about Lenin in a new Smokestack edition by Rosy Carrick

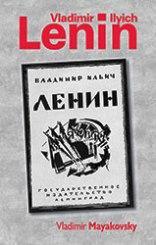

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin

Vladimir Mayakovsky

Edited & translated by Rosy Carrick

(based on a 1967 English version by Dorian Rottenberg)

Smokestack Books, 2017

ISBN 978-0-99576775-1-5

201 pages £11.99 (paperback)

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin

Vladimir Mayakovsky

Edited & translated by Rosy Carrick

(based on a 1967 English version by Dorian Rottenberg)

Smokestack Books, 2017

ISBN 978-0-99576775-1-5

201 pages £11.99 (paperback)

With the best will in the world, contemporary poetry reviewers – and, indeed, contemporary poets – cannot know, as they go about their business, what the import of the work will be. Will it last? Will the work be seen as important, and resonate with future generations of readers? Or (sadly) will most of it disappear in time’s slipstream and be lost to view?

There is no such worry in regard to Mayakovsky’s Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, a 3,000 line epic poem of 86 pages (here in a facing page bi-lingual edition, with an illuminating introduction and notes by Rosy Carrick). The book is indisputably important. Published the year after Lenin’s death in 1924, it was still enjoying multiple print runs ten years after publication (70,000 copies in 1934-35, as Carrick notes); was read live by the poet in 1930 to commemorate the sixth anniversary of his subject’s death, before a theatre audience including Stalin and prominent Party members, and broadcast on the radio. Most importantly, for the poet, it served to steer his audience towards an idealised conception of communism untainted by corruption or totalitarianism:

In 1924 … the future of communism still felt alive and malleable to Mayakovsky,

and it is this malleability which he is so keen to protect in Vladimir Ilyich Lenin

(Introduction)

Despite our knowledge of the Stalinist horrors to come, it is still fascinating to read an honest – even earnest – hymn of praise to the ideal leader. While taking time to outline the theoretical underpinnings of communism (“Marx caught/the pilferers/of surplus value/with their pelf”), and laud the more abstract aspects of Lenin’s character (he was the “genius of practice” who guided the nation “from books/to battlefields”, “the architect of victory … ranked foremost/among his equals”), the poet spends the bulk of his time stressing Lenin’s humanity: his huge forehead, average size, simplicity, even OCD-like organisational traits. He is keen to avoid building an idol of the leader garlanded with “tinsel beauty”, and cautions repeatedly against selling Lenin. Instead, Mayakovsky offers an oblique portrait (save for the occasional telling physical detail) made up of the man’s effects on the ordinary worker:

I’ve been up mountains –

not a lichen on their sides.

Just clouds

lying prone

on a rocky ledge.

The one

living soul

for hundreds of miles

was a herdsman

resplendent

with Lenin’s badge.

It is also interesting that while depersonalising the subject of his work, the poet delights in prickly caricatures of the enemy – “the manager, bald beast/flips his abacus,/blurts out ‘crisis!’/and pins up a list, DISMISSED”; “Capital,/a very hedgehog of contradictions,/bristling with bayonets,/waxed fat and strong”.

As the narrative progresses through Lenin’s radicalisation at his brother’s execution, his political education and development of the party itself, up to and beyond the point of his own death from a stroke, we are treated to an array of arresting images of practically every aspect of Soviet life but the leader. He always seems to appear obliquely, almost as an idea of humanity or distillation of its concepts, the object of constant lament or universal praise, but rarely the ordinary human Mayakovsky states he will present. It isn’t clear whether this human void is intentional – perhaps to prevent the reader projecting his or her own ideas of Lenin onto the story. Or perhaps is meant to suggest that beyond his interweaving into the soul of a new nation and its ultimate destination, the leader himself is unknowable. But whatever is the intention, the poem delivers great splendour from the thinnest of threads.

It has moments of intense poetic force – “buttock-faced police” keeping down the populace, the first world war summed up in three brutal lines as “this wholesale,/world-wide/auction of mincemeat” – but also of lyricism:

His voice sounds fainter

than a needle dropping

*

hearken to the burial mounds’ ventriloquy,

to the castanets of bones

picked clean and bare

There are occasional moments of bathos, unavoidable in such a substantial work, where a political point intrudes into the flow of the narrative or the poet falls back on tired proletarian images; and it is hard to know whether the rhyme scheme (gamely maintained by the translator) intrudes in the original, and whether its curious stepping-down form has a function beyond an inevitable sense of fragmentation in English. (It is reminiscent of some of ee cummings’ formal experiments, especially the end of ‘Nobody Loses All the Time’, but begins to grate over the long haul.) But overall, the book is bright, memorable and important. It crystallizes a historical moment before the corruption and collapse of an empire in which human hope seemed alive, politics was a world of possibility and individual lives might connect and reinforce each other in something greater than themselves. As Rosy Carrick highlights in assessing the poem’s cultural significance, quoting from the poet’s autobiography, “the workers’ attitude to it gladdened me and confirmed my conviction that the poem was needed”. Great poems always are.

Nov 17 2017

James Roderick Burns has no doubts about the importance of Mayakovsky’s epic poem about Lenin in a new Smokestack edition by Rosy Carrick

With the best will in the world, contemporary poetry reviewers – and, indeed, contemporary poets – cannot know, as they go about their business, what the import of the work will be. Will it last? Will the work be seen as important, and resonate with future generations of readers? Or (sadly) will most of it disappear in time’s slipstream and be lost to view?

There is no such worry in regard to Mayakovsky’s Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, a 3,000 line epic poem of 86 pages (here in a facing page bi-lingual edition, with an illuminating introduction and notes by Rosy Carrick). The book is indisputably important. Published the year after Lenin’s death in 1924, it was still enjoying multiple print runs ten years after publication (70,000 copies in 1934-35, as Carrick notes); was read live by the poet in 1930 to commemorate the sixth anniversary of his subject’s death, before a theatre audience including Stalin and prominent Party members, and broadcast on the radio. Most importantly, for the poet, it served to steer his audience towards an idealised conception of communism untainted by corruption or totalitarianism:

Despite our knowledge of the Stalinist horrors to come, it is still fascinating to read an honest – even earnest – hymn of praise to the ideal leader. While taking time to outline the theoretical underpinnings of communism (“Marx caught/the pilferers/of surplus value/with their pelf”), and laud the more abstract aspects of Lenin’s character (he was the “genius of practice” who guided the nation “from books/to battlefields”, “the architect of victory … ranked foremost/among his equals”), the poet spends the bulk of his time stressing Lenin’s humanity: his huge forehead, average size, simplicity, even OCD-like organisational traits. He is keen to avoid building an idol of the leader garlanded with “tinsel beauty”, and cautions repeatedly against selling Lenin. Instead, Mayakovsky offers an oblique portrait (save for the occasional telling physical detail) made up of the man’s effects on the ordinary worker:

It is also interesting that while depersonalising the subject of his work, the poet delights in prickly caricatures of the enemy – “the manager, bald beast/flips his abacus,/blurts out ‘crisis!’/and pins up a list, DISMISSED”; “Capital,/a very hedgehog of contradictions,/bristling with bayonets,/waxed fat and strong”.

As the narrative progresses through Lenin’s radicalisation at his brother’s execution, his political education and development of the party itself, up to and beyond the point of his own death from a stroke, we are treated to an array of arresting images of practically every aspect of Soviet life but the leader. He always seems to appear obliquely, almost as an idea of humanity or distillation of its concepts, the object of constant lament or universal praise, but rarely the ordinary human Mayakovsky states he will present. It isn’t clear whether this human void is intentional – perhaps to prevent the reader projecting his or her own ideas of Lenin onto the story. Or perhaps is meant to suggest that beyond his interweaving into the soul of a new nation and its ultimate destination, the leader himself is unknowable. But whatever is the intention, the poem delivers great splendour from the thinnest of threads.

It has moments of intense poetic force – “buttock-faced police” keeping down the populace, the first world war summed up in three brutal lines as “this wholesale,/world-wide/auction of mincemeat” – but also of lyricism:

His voice sounds fainter than a needle dropping * hearken to the burial mounds’ ventriloquy, to the castanets of bones picked clean and bareThere are occasional moments of bathos, unavoidable in such a substantial work, where a political point intrudes into the flow of the narrative or the poet falls back on tired proletarian images; and it is hard to know whether the rhyme scheme (gamely maintained by the translator) intrudes in the original, and whether its curious stepping-down form has a function beyond an inevitable sense of fragmentation in English. (It is reminiscent of some of ee cummings’ formal experiments, especially the end of ‘Nobody Loses All the Time’, but begins to grate over the long haul.) But overall, the book is bright, memorable and important. It crystallizes a historical moment before the corruption and collapse of an empire in which human hope seemed alive, politics was a world of possibility and individual lives might connect and reinforce each other in something greater than themselves. As Rosy Carrick highlights in assessing the poem’s cultural significance, quoting from the poet’s autobiography, “the workers’ attitude to it gladdened me and confirmed my conviction that the poem was needed”. Great poems always are.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, history, poetry reviews, politics, year 2017 0 • Tags: books, history, James Roderick Burns, poetry, politics