James Roderick Burns sees Tania Hershman’s debut collection as an exploration of uncertainty.

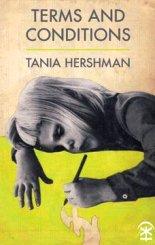

Terms and Conditions

Tania Hershman

Nine Arches Press, 2017

ISBN 9781911027225

78pp £9.99

Terms and Conditions

Tania Hershman

Nine Arches Press, 2017

ISBN 9781911027225

78pp £9.99

It is interesting that a debut collection framed in the terms of commercial contracts and obligations (its three sections entitled ‘data collection’, ‘warranties and disclaimers’ and ‘privacy policy’) turns out in the end to be all about government. The title poem, for instance, muses on the relationship between body and inhabitant:

I can’t call it mine, though …

I clean and feed it …

It sits me on this sofa, walks me to work.

Is the agreement hire-purchase?

Or am I a hotel guest?

(‘Terms and Conditions’)

One central question resonates through the book: who governs? In ‘Missing You’ (“Woman of 24 found to have no cerebellum in her brain,” New Scientist, 2014, from the endnotes) the poet suggests, rather wonderfully, that it is the unbowed human spirit which rules the roost, kicking free of such piddling constraints as physical mechanisms or functioning systems in order to thrive:

Who’s to say

she’s not finer than the rest

of us? Our signals

take no chances, walk

the roads most travelled by, while hers,

double-jointed,

are dancing

Yet at other times, she seems equally convinced (and perhaps more importantly, convincing) that we are entirely at the mercy of the physical world, even its tiniest parts binding us together irretrievably and without mercy. The narrator of the prose poem ‘Undetected’, for instance, spins out an elaborate molecular image for her attempts to rid the home of all elements of a departed partner, but is ultimately frustrated by this inescapable, intertwined quality: “I check everything again, pick up tiles and cushions, let light in, light out, clean the floor, and then I bend. Perhaps you’re right, I say out loud. But we both know, and together we sit, with beams and cross-beams, neutrinos spinning through and through and through.”

It is an unsettling poem, as is much of the book. While it is easy to find the qualities of ‘traditional’ poetry here – Hershman’s natural lyricism abounds, evident in ‘This is not my midnight’ and its depiction of the poet “time-drunk on the king-size bed/the unviewed city sugar-ripe/beyond the blackout curtains” – it is most of all a collection restlessly in search of answers, of the elusive truth behind our existence. Hershman is never content to settle simply for quality, the arresting phrase or abiding image; always there comes a deeper questing, a probing, even. “I prefer/to make friends/with uncertainty” she says (‘The uncertainty principle’), and from this difficult impulse comes much of the book’s power. It manifests itself in wry humour:

She works one day a week

in a building which also houses

a Centre for Synaptic Plasticity,

and each time she sees the sign

she wants to go in and say,

Take my brain, bend it,

it’s not behaving.

(‘For which we have no names’)

This, of course, is supposed to be at the poet’s expense, but her brain is functioning perfectly; it’s the wider human condition that is so cussed and ungovernable. Even in a poem dealing with our variable grasp on the world, and its on us (“She does not expect to be recognised/from one occasion to the next”) – which is unusual in granting a modicum of certainty, of pleasure, to the experience of being remembered – perpetual doubt creeps in:

This chips away at her

conviction of insignificance, but ohsoslowly

like the ancient lichen which grows one centimetre

every hundred years. She suspects neither of them

can change shape or pace, or let go

of what they cling to.

(‘Some nature is binding’)

Like Larkin, Hershman is perhaps less deceived than those who chose a comforting belief system over stark reality (at least as the poet sees it), and does occasionally find relief in the confirmation of what can’t be known, in the honesty of science. Here she addresses the assumption that acidification of the oceans must automatically damage coral:

Now

they find them thriving.

I had thought myself

flimsy, easily undone

by missing you. These

are questions, say the scientists,

we have no answers to.

(‘Led astray by evidence’)

The book overall is a tour de force of uncertainty, explored. If her titles occasionally become like mini-essays, over-determining the meaning of a poem (though the poems themselves often resist easy characterisation), this is a cavil. Terms and Conditions achieves a great deal in three compact sections, questioning the idea of certainty and knowledge at each step of the way (and deftly attaching what could be abstract scientific or philosophical ideas to vital frames like love, loss and longing, where they grow into each other and bear fruit), but is not as tidy and conclusive as the sections suggest. Each poem adds to an accumulating feeling of adventure, tinged with nerves, as we are never sure who or what is really in charge of the world she explores. Likening dancing to flight, and to the early consciousness of falling from the trees we slept in, Hershman provides a neat image for her debut in a few taut lines – the reader “reminded” in engaging with the book “of those forest nights, spine/pressed into the branches,/no thought of beneath”.

Sep 24 2017

James Roderick Burns sees Tania Hershman’s debut collection as an exploration of uncertainty.

It is interesting that a debut collection framed in the terms of commercial contracts and obligations (its three sections entitled ‘data collection’, ‘warranties and disclaimers’ and ‘privacy policy’) turns out in the end to be all about government. The title poem, for instance, muses on the relationship between body and inhabitant:

I can’t call it mine, though … I clean and feed it … It sits me on this sofa, walks me to work. Is the agreement hire-purchase? Or am I a hotel guest? (‘Terms and Conditions’)One central question resonates through the book: who governs? In ‘Missing You’ (“Woman of 24 found to have no cerebellum in her brain,” New Scientist, 2014, from the endnotes) the poet suggests, rather wonderfully, that it is the unbowed human spirit which rules the roost, kicking free of such piddling constraints as physical mechanisms or functioning systems in order to thrive:

Yet at other times, she seems equally convinced (and perhaps more importantly, convincing) that we are entirely at the mercy of the physical world, even its tiniest parts binding us together irretrievably and without mercy. The narrator of the prose poem ‘Undetected’, for instance, spins out an elaborate molecular image for her attempts to rid the home of all elements of a departed partner, but is ultimately frustrated by this inescapable, intertwined quality: “I check everything again, pick up tiles and cushions, let light in, light out, clean the floor, and then I bend. Perhaps you’re right, I say out loud. But we both know, and together we sit, with beams and cross-beams, neutrinos spinning through and through and through.”

It is an unsettling poem, as is much of the book. While it is easy to find the qualities of ‘traditional’ poetry here – Hershman’s natural lyricism abounds, evident in ‘This is not my midnight’ and its depiction of the poet “time-drunk on the king-size bed/the unviewed city sugar-ripe/beyond the blackout curtains” – it is most of all a collection restlessly in search of answers, of the elusive truth behind our existence. Hershman is never content to settle simply for quality, the arresting phrase or abiding image; always there comes a deeper questing, a probing, even. “I prefer/to make friends/with uncertainty” she says (‘The uncertainty principle’), and from this difficult impulse comes much of the book’s power. It manifests itself in wry humour:

She works one day a week in a building which also houses a Centre for Synaptic Plasticity, and each time she sees the sign she wants to go in and say, Take my brain, bend it, it’s not behaving. (‘For which we have no names’)This, of course, is supposed to be at the poet’s expense, but her brain is functioning perfectly; it’s the wider human condition that is so cussed and ungovernable. Even in a poem dealing with our variable grasp on the world, and its on us (“She does not expect to be recognised/from one occasion to the next”) – which is unusual in granting a modicum of certainty, of pleasure, to the experience of being remembered – perpetual doubt creeps in:

This chips away at her conviction of insignificance, but ohsoslowly like the ancient lichen which grows one centimetre every hundred years. She suspects neither of them can change shape or pace, or let go of what they cling to. (‘Some nature is binding’)Like Larkin, Hershman is perhaps less deceived than those who chose a comforting belief system over stark reality (at least as the poet sees it), and does occasionally find relief in the confirmation of what can’t be known, in the honesty of science. Here she addresses the assumption that acidification of the oceans must automatically damage coral:

Now they find them thriving. I had thought myself flimsy, easily undone by missing you. These are questions, say the scientists, we have no answers to. (‘Led astray by evidence’)The book overall is a tour de force of uncertainty, explored. If her titles occasionally become like mini-essays, over-determining the meaning of a poem (though the poems themselves often resist easy characterisation), this is a cavil. Terms and Conditions achieves a great deal in three compact sections, questioning the idea of certainty and knowledge at each step of the way (and deftly attaching what could be abstract scientific or philosophical ideas to vital frames like love, loss and longing, where they grow into each other and bear fruit), but is not as tidy and conclusive as the sections suggest. Each poem adds to an accumulating feeling of adventure, tinged with nerves, as we are never sure who or what is really in charge of the world she explores. Likening dancing to flight, and to the early consciousness of falling from the trees we slept in, Hershman provides a neat image for her debut in a few taut lines – the reader “reminded” in engaging with the book “of those forest nights, spine/pressed into the branches,/no thought of beneath”.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2017 0 • Tags: books, James Roderick Burns, poetry