Poetry review – CONTINUOUS CREATION; Stuart Henson reviews Les Murray’s last full collection

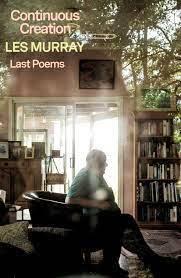

Continuous Creation

Les Murray

Carcanet

ISBN 978-1-80017-174-9

£11.99

Continuous Creation

Les Murray

Carcanet

ISBN 978-1-80017-174-9

£11.99

The last complete book by a great poet is a significant landmark. No doubt there will be Collecteds in new editions, opportunities to look back and evaluate, reassess—but this is something different. As Jamie Grant explains in his ‘Note on the Text’ Les Murray had ‘about three-quarters of a new book ready’ five months before his death in April 2019. The remaining quarter of Continuous Creation was taken from the box of typed and handwritten drafts that Murray left by the desk at his Bunyah house.

The first thing that should be said is that it’s by no means a gathering of odds and ends. There aren’t any poems of the length of ‘Toward the Imminent Days’ or ‘North Country Suite’ but even the shortest pieces here feel worked-on and polished. Some are wry, almost throw-away, like the one about his successful contesting of a Dangerous Driving charge, (The court costs turned out more than the fine would have been.) but most, as fans of Les Murray would expect, are drawn from his penetrating observation of natural and human worlds. It could be a pile of twigs and leaves on the road that turns out not to be a kangaroo sleeping, or the physical sensations—sight, sound, scents—of ‘Testing the Chainsaws’:

Cross cut and long cut,

test splits and loud chaw,

dry blade with grit pouring,

blood heaped on the floor.

Up-angled many-severed

black toast-crusty ends

clamped in ring steel.

Crack-faced open lightnings

ham sliced parallel,

fragrant screamy choc burr,

pistol gripped and urged well.

Simple enough you think—until you begin to hear the subtle onomatopoeic things that are going on inside the lines, observe the rhymes, reflect on the hints that lie behind the substitution of ‘blood’ for sawdust, relish the sheer visual joys of ‘black toast-crusty ends’ and ‘Crack-faced open lightnings’… And that last verb, ‘urged’: so right for the way you push a chainsaw into the wood as it bites.

Les Murray was often linked, in a kind of super-group, with Brodsky, Walcott and Heaney—the ‘Fab Four’ of international poetry—and certainly you can see a Heaney-esque ‘discovery’ of things hidden in plain sight in short poems like ‘Trimming Plumbago’, which begins with ‘musical gasps ‘ as ‘the cane-knife comes / shaving the swollen / skirts of the hedgerow’ and ends with a close examination of the ‘old-shaped blade’ with its new ‘white edge / fresh and narrow as cotton’. But Murray’s imagery could just as easily be said to be Hughesean when he’s engaging with the natural world. Take this stanza from ‘Speed’, which turns out to be, surprisingly, about a giraffe:

and we see the lioness

erupt out of cover

to be shed, stomped,

rolled like a motorbike

under an express train.

Again, what precision with the verb ‘erupt’—and the wonderful simile of the motorbike and the express train! Collision, violence, the visual, rendered in language like the compulsive slow-motion that’s so often used in action movies and wildlife films. Murray’s undimmed verbal energy is there again in the bush tale of ‘Lightning Strike by Phone’ in which his aunt’s house takes a direct hit:

a ball of lightning formed out along

the verandah, came snorting and strumming

to the door, and sucked inside

straight into the video, which came on

and displayed all it knew, its numbers,

all its jittering pathetic ruined numbers

that would never sing again…

If Nature and Man is one of Murray’s big themes, another might be history, and as Murray once put it ‘the relations between human time and eternity’. Continuous Creation draws, as he has done before, on the family histories of the Murrays, the Morellis and the Arnalls. We encounter Fred Arnall, his mother’s father, mining alunite ‘from an upside-down mine / tunnelled inside a mountain’ and dead of a lung disease by the age of fifty; also Murray’s wife’s grandfather, Balz, with Berta, Balz’s adopted daughter. The sweep of time and the vicissitudes of the immigrant experience are crystallised in ‘Balz’s Fosterling’ and ‘Exile’, and every two-decade span of Australia’s Twentieth Century gets a neat summing-up in a new version of ‘The Scores’—a poem that first appeared in the 2002 collection Poems the Size of Photographs.

Murray’s approach is naturally more show than tell, as in ‘Laze Creates Island’ which vividly evokes the visual wonder of a coastal volcanic eruption—and as here, in the eight short lines of ‘Verticals’:

Whizz of blue striped

curtains on a rail

and beyond those, the dull

downrights of sheet iron

wrapped around fruit trees

to fence off horse-rubbing,

donkey-scrape, and the horns

which used to grind sugar.

This is painterly—or a verbal equivalent of the photos included in the 2015 Carcanet collection On Bunyah, that seem, in their turn like poems themselves. The title poem of this book (appropriately chosen by Jamie Grant) sums it all up:

We bring nothing into this world

except our gradual ability

to create it, out of all that vanishes

and all that will outlast us.

For European readers, the ‘otherness’ of Murray’s Australia is part of the fascination. Pippies, catbirds, weebills, lilli-pilli trees… exotic to the British ear. Even the small change you might pocket without thinking: ‘designer Devlin’s sculpture / of the duckbilled animal / swimming up to the top swirl…’ How many Poms like me will remember wondering at that unfamiliar creature captured in their childhood collection of foreign coins? There are some phenomena that will be more familiar to us from news coverage. ‘On Bushfire Warning Day’ puzzles over what to take with you when flames threaten your home. Murray’s choices are practical (‘money cards / clothing…’) and pragmatic (Where would we go? / Newcastle, at best, / or else as roads were open) though one is significant in ways that might not at first be apparent: he selects ‘Clare’s albums’ among his escape-treasures. These, Grant explains in his Note, are the ‘three massive volumes’ of images, postcards, photos, bits of verse, weird newspaper snippets and labels that Les Murray collected and left alongside the drafts in his study. His daughter Clare had given these big old-style ledgers the title ‘The Great Book’ and they contain the source material for decades of poems. If a bush fire had struck, Murray might well have been without a roof, but he wouldn’t have been without inspiration. The poem ends with three stanzas of reflection:

Would we come back?

If the house survived, yes,

even if all remaining were

tiles and fuselage metal.

Erasure might be

a sort of rebirthing,

a new tune, higher strung,

new ceiling for new clouds –

If we stayed gone

we’d be pestilent lore,

present in our past

crowding the new people.

His attachment to the forty acres he eventually bought back, land that his father never owned, is a powerful force in Murray’s work. Like his aboriginal neighbours, like John Clare, his relationship to his landscape is sacramental. It’s not by chance, I think, that the last poem in this last collection encapsulates—retelling with elliptical economy—the story of Murray’s biography. Its title is ‘The Mystery’, and for a poet who dedicated each of his volumes ‘To the glory of God’ it’s a title that resonates profoundly. Although he distances his young self into the third person, Murray takes us back to the defining moment of his life, the loss of his mother when he was twelve, and shows us again the image that struck him inexplicably at the time:

A black hearse of Howards

undertakers of Taree

leads a long procession

toward Krambach’s paddock cemetery.

As it passes Purfleet,

the aboriginal mission, old Mr

Lobban, Uncle Eddie

last initiated man

of the Kattang, stands beside

the then gravel road, with hat

doffed, as no one ever sees it.

The old man’s reverence for life, the significance of his never-before-seen gesture across cultures, has communicated something the numbed child will take a lifetime to understand—or perhaps it would be truer to say that the child has registered through a glass darkly a principle that takes many of us a lifetime to formulate. His mother’s death, his father’s collapse, the family disputes and recriminations, his own bitter self-consciousness… all part of the mystery. Murray’s life work was so often caught up in the attempt to reconcile the suffering of the past with the brief joys of the present, and to understand the relationship of a man to his native land through creative endeavour. Most fitting, then, that the last word of this last poem is Bunyah.

Jul 4 2022

London Grip Poetry Review – Les Murray

Poetry review – CONTINUOUS CREATION; Stuart Henson reviews Les Murray’s last full collection

The last complete book by a great poet is a significant landmark. No doubt there will be Collecteds in new editions, opportunities to look back and evaluate, reassess—but this is something different. As Jamie Grant explains in his ‘Note on the Text’ Les Murray had ‘about three-quarters of a new book ready’ five months before his death in April 2019. The remaining quarter of Continuous Creation was taken from the box of typed and handwritten drafts that Murray left by the desk at his Bunyah house.

The first thing that should be said is that it’s by no means a gathering of odds and ends. There aren’t any poems of the length of ‘Toward the Imminent Days’ or ‘North Country Suite’ but even the shortest pieces here feel worked-on and polished. Some are wry, almost throw-away, like the one about his successful contesting of a Dangerous Driving charge, (The court costs turned out more than the fine would have been.) but most, as fans of Les Murray would expect, are drawn from his penetrating observation of natural and human worlds. It could be a pile of twigs and leaves on the road that turns out not to be a kangaroo sleeping, or the physical sensations—sight, sound, scents—of ‘Testing the Chainsaws’:

Simple enough you think—until you begin to hear the subtle onomatopoeic things that are going on inside the lines, observe the rhymes, reflect on the hints that lie behind the substitution of ‘blood’ for sawdust, relish the sheer visual joys of ‘black toast-crusty ends’ and ‘Crack-faced open lightnings’… And that last verb, ‘urged’: so right for the way you push a chainsaw into the wood as it bites.

Les Murray was often linked, in a kind of super-group, with Brodsky, Walcott and Heaney—the ‘Fab Four’ of international poetry—and certainly you can see a Heaney-esque ‘discovery’ of things hidden in plain sight in short poems like ‘Trimming Plumbago’, which begins with ‘musical gasps ‘ as ‘the cane-knife comes / shaving the swollen / skirts of the hedgerow’ and ends with a close examination of the ‘old-shaped blade’ with its new ‘white edge / fresh and narrow as cotton’. But Murray’s imagery could just as easily be said to be Hughesean when he’s engaging with the natural world. Take this stanza from ‘Speed’, which turns out to be, surprisingly, about a giraffe:

Again, what precision with the verb ‘erupt’—and the wonderful simile of the motorbike and the express train! Collision, violence, the visual, rendered in language like the compulsive slow-motion that’s so often used in action movies and wildlife films. Murray’s undimmed verbal energy is there again in the bush tale of ‘Lightning Strike by Phone’ in which his aunt’s house takes a direct hit:

If Nature and Man is one of Murray’s big themes, another might be history, and as Murray once put it ‘the relations between human time and eternity’. Continuous Creation draws, as he has done before, on the family histories of the Murrays, the Morellis and the Arnalls. We encounter Fred Arnall, his mother’s father, mining alunite ‘from an upside-down mine / tunnelled inside a mountain’ and dead of a lung disease by the age of fifty; also Murray’s wife’s grandfather, Balz, with Berta, Balz’s adopted daughter. The sweep of time and the vicissitudes of the immigrant experience are crystallised in ‘Balz’s Fosterling’ and ‘Exile’, and every two-decade span of Australia’s Twentieth Century gets a neat summing-up in a new version of ‘The Scores’—a poem that first appeared in the 2002 collection Poems the Size of Photographs.

Murray’s approach is naturally more show than tell, as in ‘Laze Creates Island’ which vividly evokes the visual wonder of a coastal volcanic eruption—and as here, in the eight short lines of ‘Verticals’:

This is painterly—or a verbal equivalent of the photos included in the 2015 Carcanet collection On Bunyah, that seem, in their turn like poems themselves. The title poem of this book (appropriately chosen by Jamie Grant) sums it all up:

For European readers, the ‘otherness’ of Murray’s Australia is part of the fascination. Pippies, catbirds, weebills, lilli-pilli trees… exotic to the British ear. Even the small change you might pocket without thinking: ‘designer Devlin’s sculpture / of the duckbilled animal / swimming up to the top swirl…’ How many Poms like me will remember wondering at that unfamiliar creature captured in their childhood collection of foreign coins? There are some phenomena that will be more familiar to us from news coverage. ‘On Bushfire Warning Day’ puzzles over what to take with you when flames threaten your home. Murray’s choices are practical (‘money cards / clothing…’) and pragmatic (Where would we go? / Newcastle, at best, / or else as roads were open) though one is significant in ways that might not at first be apparent: he selects ‘Clare’s albums’ among his escape-treasures. These, Grant explains in his Note, are the ‘three massive volumes’ of images, postcards, photos, bits of verse, weird newspaper snippets and labels that Les Murray collected and left alongside the drafts in his study. His daughter Clare had given these big old-style ledgers the title ‘The Great Book’ and they contain the source material for decades of poems. If a bush fire had struck, Murray might well have been without a roof, but he wouldn’t have been without inspiration. The poem ends with three stanzas of reflection:

His attachment to the forty acres he eventually bought back, land that his father never owned, is a powerful force in Murray’s work. Like his aboriginal neighbours, like John Clare, his relationship to his landscape is sacramental. It’s not by chance, I think, that the last poem in this last collection encapsulates—retelling with elliptical economy—the story of Murray’s biography. Its title is ‘The Mystery’, and for a poet who dedicated each of his volumes ‘To the glory of God’ it’s a title that resonates profoundly. Although he distances his young self into the third person, Murray takes us back to the defining moment of his life, the loss of his mother when he was twelve, and shows us again the image that struck him inexplicably at the time:

The old man’s reverence for life, the significance of his never-before-seen gesture across cultures, has communicated something the numbed child will take a lifetime to understand—or perhaps it would be truer to say that the child has registered through a glass darkly a principle that takes many of us a lifetime to formulate. His mother’s death, his father’s collapse, the family disputes and recriminations, his own bitter self-consciousness… all part of the mystery. Murray’s life work was so often caught up in the attempt to reconcile the suffering of the past with the brief joys of the present, and to understand the relationship of a man to his native land through creative endeavour. Most fitting, then, that the last word of this last poem is Bunyah.