Poetry review – BEAUTIFUL LOFTY THINGS: Michael Bartholomew-Biggs enjoys his examination of Cahal Dallat’s poetic version of a cabinet of curiosities

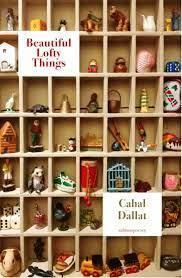

Beautiful Lofty Things

Cahal Dallat

Salmon Poetry

ISBN 9781915 022073

12 euros

Beautiful Lofty Things

Cahal Dallat

Salmon Poetry

ISBN 9781915 022073

12 euros

In his new collection Beautiful Lofty Things, Cahal Dallat interrogates his own past in poems inspired by found objects as diverse as pocket knives, banknotes, book covers and binoculars. Some of the questions raised are relatively easily answered: for instance, what lies concealed in the seaman’s trunk whose hasps must be jemmied open? Others yield answers only with the passage of time: what motivated the poet’s solitary night-time walk from Rhens to Koblenz? And some puzzles are probably unsolvable: how and why did the poet’s father come into possession of an ex-KGB micro camera?

The poems draw strongly on the poet’s Irish roots and introduce us to his family, friends and colleagues, both present and past. Some of the reaching into the past goes beyond the purely domestic and touches on painful connections with Ireland’s troubled history with mentions of betrayals and executions – “a golden hemp-rope adorning that fine, stiff, Sherard neck.”

A lighter vein predominates, however, and there are frequent reminders that Dallat (like his father) is an accomplished musician and something of a musicologist. Song titles and other musical references run through the collection like signposts on a journey back and forth through time. ‘Shakin’ All Over’ recalls the 1960s and reveals a detailed knowledge of the frequent and rapid shifts of personnel between the popular groups of the day. It also reminds us of the road accident that ended both the career and the life of singer Johnny Kidd. ‘My Way’ meanders into the subject of miniature music boxes and indulges in the teasing speculation

Winding it

anti-clockwise Paternoster-like might yet

undo those hideous backward decades

Perhaps playing a song backwards could indeed undo an unhappy past as effectively as the recorded sounds on an old reel-to-reel Grundig machine can bestow the gift of mental and emotional time-travel

… the room suddenly rich

in fugitive light with your mother’s lost

voice, sheer essence of dancehall longing

before all manner of things would cease to be

well …

['Naming']

Rewinding the past for inspection – even if not for repair – is the core business of this collection. ‘Time Enough’ remembers the poet’s father being teased by “easy-going West coast shark-fishers” for his “restless Northern go” and reminded that “When God made time … He made plenty.” The book’s title poem discovers and opens

this battered cardboard box of hours,

of every clock that ever failed the test

of time, the clocks that time forgot

That last line illustrates Dallat’s fondness for playing with familiar phrases – as he also does in a poem about dead men’s shoes which contains an exhortation to “bless his little coffin socks.” He has a keen ear for literary resonances too, as shown in a poem which mentions bars and cocktails and then rearranges Shakespeare in order to speak of “Singapore’s outrageous Slings.”

The poems are mostly reflective in tone but in at least one case there is a fine sense of dramatic action: ‘Render unto’ reveals what it is like to be in a multi-car pile-up on the motorway and careering

back down the fast lane on our side

to face the battalions of halogens

snapping at us; and we reach each

for the other's hand...

In contrast, ‘How It Was’ deals with a much quieter memory (which also involves continental roads). It can be very difficult to capture afterwards the magical strangeness of those moments on a journey which stick in the mind for no obvious reason; but Dallat here accomplishes it perfectly

their coach driver

took them off-road to a local

tavern by Arras's serried dead ranks

where they drank smaller coffees

than they'd ever seen before, beneath

the baleful gaze of two black wolves

The poem ‘Utterances’ occurs roughly at the midpoint of the book and recalls an incident in Paris. Its second verse runs as follows

when I ask in a feast of enunciation Combien –

ca coûte – cette boite de ‘Marmite Cubes’ and the vendeur

rasps in Marlboro English O, say it again,

je just adore le francais with a North Antrim accent

Here we can see several recurring elements of the collection’s distinctive content and style. There is the cheeky pun on “annunciation”; the free-handed injection of foreign language fragments; another reminder of the poet’s place of origin. It is also noteworthy – and fairly typical –that these four lines are part of a single fourteen-line sentence with at least one parenthetical digression and other diversions en route. Similar linguistic and imaginative exuberance is to be found in ‘Collectives’ – a selection of suggested collective nouns which includes “a desolation of lean-tos” – and also in ‘The Witnesses’ which compares the composition of the famous Arnolfini Wedding painting to the taking of a selfie so as to “lose the close-up convex convict look” and at the same time

.... get the zoom right and

miss

the two doorway reflections he won't be able

to crop later.

All these very positive things being said, I do also have some mild reservations. The first, which is not really the responsibility of the poet, is that some images of the inspirational objects seem needlessly small and unclear. Those which include printing or handwriting could have been made large enough to be readable; and those, like ‘After’ and ‘Collectives’, which present a picture of a picture might have benefited by being in colour. In regard to the poems themselves, I feel that the long and intricately worked sentences do not always work as well as was the case in ‘Utterances’. This may partly be due to Dallat’s fondness for throwing in many brief and oblique references – literary and otherwise –which he trusts his readers will pick up. This reader was not always equal to the poet’s expectations! (I did unravel the convoluted mention of Wallace Stevens and his The Emperor of Ice-Cream but I failed to identify the Emily Dickinson quote prompted by the image of a Swiss Army knife.) At times the poems feel rather like well-phrased crossword clues whose solutions lie in Dallat’s extensive database of arcane items of general knowledge (frequently deployed in his role as quiz-setter for end-of-term events at the Troubadour poetry venue). Perhaps it would have been a generous gesture to include a page or two of end notes? Nevertheless, even without such assistance, a few moments of puzzlement might be reckoned a small matter when set against the overall enjoyment of a provocative and substantial collection which assuredly repays many re-readings.

Jul 8 2022

London Grip Poetry Review – Cahal Dallat

Poetry review – BEAUTIFUL LOFTY THINGS: Michael Bartholomew-Biggs enjoys his examination of Cahal Dallat’s poetic version of a cabinet of curiosities

In his new collection Beautiful Lofty Things, Cahal Dallat interrogates his own past in poems inspired by found objects as diverse as pocket knives, banknotes, book covers and binoculars. Some of the questions raised are relatively easily answered: for instance, what lies concealed in the seaman’s trunk whose hasps must be jemmied open? Others yield answers only with the passage of time: what motivated the poet’s solitary night-time walk from Rhens to Koblenz? And some puzzles are probably unsolvable: how and why did the poet’s father come into possession of an ex-KGB micro camera?

The poems draw strongly on the poet’s Irish roots and introduce us to his family, friends and colleagues, both present and past. Some of the reaching into the past goes beyond the purely domestic and touches on painful connections with Ireland’s troubled history with mentions of betrayals and executions – “a golden hemp-rope adorning that fine, stiff, Sherard neck.”

A lighter vein predominates, however, and there are frequent reminders that Dallat (like his father) is an accomplished musician and something of a musicologist. Song titles and other musical references run through the collection like signposts on a journey back and forth through time. ‘Shakin’ All Over’ recalls the 1960s and reveals a detailed knowledge of the frequent and rapid shifts of personnel between the popular groups of the day. It also reminds us of the road accident that ended both the career and the life of singer Johnny Kidd. ‘My Way’ meanders into the subject of miniature music boxes and indulges in the teasing speculation

Perhaps playing a song backwards could indeed undo an unhappy past as effectively as the recorded sounds on an old reel-to-reel Grundig machine can bestow the gift of mental and emotional time-travel

… the room suddenly rich in fugitive light with your mother’s lost voice, sheer essence of dancehall longing before all manner of things would cease to be well … ['Naming']Rewinding the past for inspection – even if not for repair – is the core business of this collection. ‘Time Enough’ remembers the poet’s father being teased by “easy-going West coast shark-fishers” for his “restless Northern go” and reminded that “When God made time … He made plenty.” The book’s title poem discovers and opens

That last line illustrates Dallat’s fondness for playing with familiar phrases – as he also does in a poem about dead men’s shoes which contains an exhortation to “bless his little coffin socks.” He has a keen ear for literary resonances too, as shown in a poem which mentions bars and cocktails and then rearranges Shakespeare in order to speak of “Singapore’s outrageous Slings.”

The poems are mostly reflective in tone but in at least one case there is a fine sense of dramatic action: ‘Render unto’ reveals what it is like to be in a multi-car pile-up on the motorway and careering

In contrast, ‘How It Was’ deals with a much quieter memory (which also involves continental roads). It can be very difficult to capture afterwards the magical strangeness of those moments on a journey which stick in the mind for no obvious reason; but Dallat here accomplishes it perfectly

The poem ‘Utterances’ occurs roughly at the midpoint of the book and recalls an incident in Paris. Its second verse runs as follows

Here we can see several recurring elements of the collection’s distinctive content and style. There is the cheeky pun on “annunciation”; the free-handed injection of foreign language fragments; another reminder of the poet’s place of origin. It is also noteworthy – and fairly typical –that these four lines are part of a single fourteen-line sentence with at least one parenthetical digression and other diversions en route. Similar linguistic and imaginative exuberance is to be found in ‘Collectives’ – a selection of suggested collective nouns which includes “a desolation of lean-tos” – and also in ‘The Witnesses’ which compares the composition of the famous Arnolfini Wedding painting to the taking of a selfie so as to “lose the close-up convex convict look” and at the same time

.... get the zoom right and miss the two doorway reflections he won't be able to crop later.All these very positive things being said, I do also have some mild reservations. The first, which is not really the responsibility of the poet, is that some images of the inspirational objects seem needlessly small and unclear. Those which include printing or handwriting could have been made large enough to be readable; and those, like ‘After’ and ‘Collectives’, which present a picture of a picture might have benefited by being in colour. In regard to the poems themselves, I feel that the long and intricately worked sentences do not always work as well as was the case in ‘Utterances’. This may partly be due to Dallat’s fondness for throwing in many brief and oblique references – literary and otherwise –which he trusts his readers will pick up. This reader was not always equal to the poet’s expectations! (I did unravel the convoluted mention of Wallace Stevens and his The Emperor of Ice-Cream but I failed to identify the Emily Dickinson quote prompted by the image of a Swiss Army knife.) At times the poems feel rather like well-phrased crossword clues whose solutions lie in Dallat’s extensive database of arcane items of general knowledge (frequently deployed in his role as quiz-setter for end-of-term events at the Troubadour poetry venue). Perhaps it would have been a generous gesture to include a page or two of end notes? Nevertheless, even without such assistance, a few moments of puzzlement might be reckoned a small matter when set against the overall enjoyment of a provocative and substantial collection which assuredly repays many re-readings.