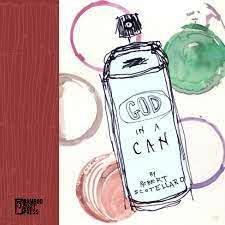

GOD IN A CAN: Charles Rammelkamp reviews a new collection of flash fiction by Robert Scotellaro

God in a Can

Robert Scotellaro

Bamboo Dart Press, 2022

ISBN: 978-1947240438

56 pp $7.99

God in a Can

Robert Scotellaro

Bamboo Dart Press, 2022

ISBN: 978-1947240438

56 pp $7.99

Robert Scotellaro’s vivid fiction operates in an absurd world, which at once defangs the horror of a 1984-like police state, say, with Honeymooners-like slapstick (“P’s & Q’s”) or a Buffy-the-Vampire-Slayer world in which Hell really does come to Earth (hilariously in a breakfast diner in “”Hell Climbs Up”). The farcical scenarios of his micro fictions have a Woody Allen-esque craziness that makes the reader laugh out loud, and that’s not just a figure of speech. The lonely widow in “Small Talk” who ameliorates her heartache with programmable appliances that talk to her brings a smile even as we recognize the sad impulse behind her purchases. When she reads about the “Sexy-Talk Dishwasher” in the catalogue (“It came with an accents setting and a variety of voice modulations”), her refrigerator mutters one of its canned phrases: “Now ain’t that somethin’.” “Now you just hush,” Sylvie chides from her recliner.

The epigraph to God in a Can, by the Argentinian writer Julio Cortázar, is spot on: “Only by living absurdly is it possible to break out of this infinite absurdity.” This is the method to Scotallero’s madness. In the story, “Damn the Torpedoes,” in which a man’s dog, like a licensed psychiatrist, gives him sound relationship advice when the man, in the throes of self-pity, aims a gun at his head (“Jazzie’s been cheatin’ on you for a long time. She’s a slut, and you deserve better. You’ll get better.”), Scotty essentially shows us his hand, telling us what he’s up to in these hilarious stories, when the man reacts to his dog, “feeling like he was in a bizarro dream version of a cartoon he’d seen as a kid where a hound talked. That perhaps some dreamscape had split open and the dark forces were spilling out.” Exactly!

Scotallero’s jokes are exquisitely literary at times. In “The Metamorphosis (Revisited),” a man doesn’t wake up as bug, but as a thingamajig, a gizmo, buttons, cranks, levers and doohickeys all over himself. Aghast, he confronts his wife. “‘Madge,’ he says. What the hell?’ But Madge takes it all in stride. “You know, let’s not be negative. I bet you’ll come in handy in ways you can’t even imagine.”

“Crooners on the Web” features some of the very witty phrasing Scotty excels at, almost slapstick, which he always brings together with an insightful punch to the gut. In this story, a poet is interviewing at an employment agency. Of course, he has zero practical skills, but he’s a consummate wisecracker. When the man behind the desk, wearing a necktie featuring golfers poised to swing, observes, “On your information form you list Poet,” the poet jokes, telling the official he can do impressions and then mimes a T-Rex pantomiming a warm embrace. It goes on like this, the poet essentially mocking the interviewer, who offers various clerical and manual job possibilities, until the man with the golfer necktie gives as good as he gets, poetic in his own right:

The man cleared his throat and swung the binder shut. “When bear traps

sing, it’s usually with their mouths full,” he said. “You think I like this

crap? Don’t mistake a fly buzzing in a web for a crooner. I was young

once.”

Chastised, “The poet straightened in his chair.”

We all have dreams, right?

Indeed, there is something of the moral fable or fairy tale going on in so many of these stories. The title story, for instance, is something like the genie in the lantern who grants three wishes that the protagonist inevitably screws up out of greed and carelessness, the usual human failings. God in a can backfires on the protagonist of this little gem when he misuses the aerosol he’s picked up at the Specialty Shop. Or, reminiscent of Icarus, they are doomed like the “Cloud Walkers”: “Too heavy a meal or lack of concentration and there is always a trapdoor waiting.” “Mad Hatters” is another fable-like flash that’s uncomfortably close to a Vladimir Putin tyrant, whose end is all too uncertain.

Only by living absurdly do we break out of the absurd! Or, as the fortune-cookie writer in “That’s When We’ll Hear the Birds Sing” puts it: “Life is a beverage best sucked through a paper straw that keeps collapsing.” … Wha’?

Jul 9 2022

God in a Can

GOD IN A CAN: Charles Rammelkamp reviews a new collection of flash fiction by Robert Scotellaro

Robert Scotellaro’s vivid fiction operates in an absurd world, which at once defangs the horror of a 1984-like police state, say, with Honeymooners-like slapstick (“P’s & Q’s”) or a Buffy-the-Vampire-Slayer world in which Hell really does come to Earth (hilariously in a breakfast diner in “”Hell Climbs Up”). The farcical scenarios of his micro fictions have a Woody Allen-esque craziness that makes the reader laugh out loud, and that’s not just a figure of speech. The lonely widow in “Small Talk” who ameliorates her heartache with programmable appliances that talk to her brings a smile even as we recognize the sad impulse behind her purchases. When she reads about the “Sexy-Talk Dishwasher” in the catalogue (“It came with an accents setting and a variety of voice modulations”), her refrigerator mutters one of its canned phrases: “Now ain’t that somethin’.” “Now you just hush,” Sylvie chides from her recliner.

The epigraph to God in a Can, by the Argentinian writer Julio Cortázar, is spot on: “Only by living absurdly is it possible to break out of this infinite absurdity.” This is the method to Scotallero’s madness. In the story, “Damn the Torpedoes,” in which a man’s dog, like a licensed psychiatrist, gives him sound relationship advice when the man, in the throes of self-pity, aims a gun at his head (“Jazzie’s been cheatin’ on you for a long time. She’s a slut, and you deserve better. You’ll get better.”), Scotty essentially shows us his hand, telling us what he’s up to in these hilarious stories, when the man reacts to his dog, “feeling like he was in a bizarro dream version of a cartoon he’d seen as a kid where a hound talked. That perhaps some dreamscape had split open and the dark forces were spilling out.” Exactly!

Scotallero’s jokes are exquisitely literary at times. In “The Metamorphosis (Revisited),” a man doesn’t wake up as bug, but as a thingamajig, a gizmo, buttons, cranks, levers and doohickeys all over himself. Aghast, he confronts his wife. “‘Madge,’ he says. What the hell?’ But Madge takes it all in stride. “You know, let’s not be negative. I bet you’ll come in handy in ways you can’t even imagine.”

“Crooners on the Web” features some of the very witty phrasing Scotty excels at, almost slapstick, which he always brings together with an insightful punch to the gut. In this story, a poet is interviewing at an employment agency. Of course, he has zero practical skills, but he’s a consummate wisecracker. When the man behind the desk, wearing a necktie featuring golfers poised to swing, observes, “On your information form you list Poet,” the poet jokes, telling the official he can do impressions and then mimes a T-Rex pantomiming a warm embrace. It goes on like this, the poet essentially mocking the interviewer, who offers various clerical and manual job possibilities, until the man with the golfer necktie gives as good as he gets, poetic in his own right:

Chastised, “The poet straightened in his chair.”

We all have dreams, right?

Indeed, there is something of the moral fable or fairy tale going on in so many of these stories. The title story, for instance, is something like the genie in the lantern who grants three wishes that the protagonist inevitably screws up out of greed and carelessness, the usual human failings. God in a can backfires on the protagonist of this little gem when he misuses the aerosol he’s picked up at the Specialty Shop. Or, reminiscent of Icarus, they are doomed like the “Cloud Walkers”: “Too heavy a meal or lack of concentration and there is always a trapdoor waiting.” “Mad Hatters” is another fable-like flash that’s uncomfortably close to a Vladimir Putin tyrant, whose end is all too uncertain.

Only by living absurdly do we break out of the absurd! Or, as the fortune-cookie writer in “That’s When We’ll Hear the Birds Sing” puts it: “Life is a beverage best sucked through a paper straw that keeps collapsing.” … Wha’?