May 31 2022

London Grip Poetry Review – Síofra McSherry

Poetry review – REQUIEM: P.W. Bridgman takes an in-depth look at Síofra McSherry’s long poem which faces loss and death

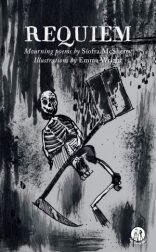

REQUIEM Síofra McSherry (with illustrations by Emma Wright) The Emma Press ISBN 978-1-912915-40-8 36 pp. £5

There are as many ways to confront the death of a loved one as there are people in the world. It is life experience that prepares us, to the extent we ever can be prepared, to face such a death. No one person’s life experience is the same as the next, just as no one’s relationship with a lost one can be the same as any other’s.

But there are commonalities in human responses to deaths of this kind. Among them are attitudes of acceptance and resignation. The first does not imply the second. Far from it. Inherent in acceptance is a recognition that some things lie outside one’s control, and that once that is conceded, one can actively manage one’s responses to loss by (for example) embracing, as valid, the way loss feels in the wake of it. Resignation, by contrast, carries the connotation of surrender—of experiencing loss as a defeat to which one must inevitably and ineluctably yield. Resignation is a more passive reaction to death, with less personal agency in play and, q.e.d., less resolution. You will find no hint of resignation in Síofra McSherry’s stunning and affecting long poem, Requiem.

Edna St Vincent Millay captured the difference between acceptance and resignation in the face of death in one of the finest poems ever written on the subject, her aptly titled “I Am Not Resigned”. Like McSherry’s, Millay’s response to the death of someone dear was a reluctant acceptance. It had none of the trappings, none of the defeatism, of resignation. Indeed, Millay staunchly and expressly refused to be resigned:

I am not resigned to the shutting away of loving hearts in the hard ground. So it is, and so it will be, for so it has been, time out of mind: Into the darkness they go, the wise and the lovely. Crowned With lilies and with laurel they go; but I am not resigned… Down, down, down into the darkness of the grave Gently they go, the beautiful, the tender, the kind; Quietly they go, the intelligent, the witty, the brave. I know. But I do not approve. And I am not resigned.

These sentiments of Millay’s seem to toll quietly yet insistently in the background of McSherry’s Requiem. Published as a chapbook by the ever-discerning Emma Press, Requiem is a final and fierce tribute to McSherry’s mother who succumbed to motor neurone disease. It is a book of “mourning poems” as she put it. Its various parts comprise an elegy and, as such, it “chart[s]… how after is different from before”. (The quote is from Stephen Sexton’s article, “The Changing Mountain”, published in Poetry London’s summer 2020 issue. McSherry’s Requiem is mentioned there.)

Life after her mother’s death certainly differs from the way it was for McSherry. But Requiem stands as a brave and proud memorial that extends the reach of her mother’s life past its natural end. As the poet says, “What is remembered lives”.

Fundamental to this somewhat experimental work is the fact that Requiem is built on the formal scaffolding of the Requiem Mass. It is thus first approached by the reader, by dint of its title and its structure, with a measure of anticipatory reverence. The language of Requiem passes through many registers and, so, it only occasionally recalls the sombre incantation of holy writ by a stooped and aging priest. But the structural, liturgical bones of Requiem are never far from sight. They can be discerned, as it were, pushing gently through the contours and plaits of the shroud. McSherry’s juxtaposition of varying modes of expression against the angular and formal framework of an end-of-life liturgy works a special kind of magic. Hence, for the reader, a reverence of a sort persists, although the changing voices of Requiem allow McSherry room to move, room to express anger and regret artfully, room to chastise God, room to mock Him and His comforting assurances, room to do something Bruce Cockburn aimed to do in a line from his song, “Lovers in a Dangerous Time”, namely, “…kick at the darkness until it bleeds daylight”.

The bleak momentousness of McSherry’s deep loss is well captured in the Introitus:

…Your veils shall set fast our limbs, swaddle our mouths and noses, our eyes and ears and skin. We shall speak nothing, hear nothing, see nothing. Nothing shall be known. Before you sense is scattered and meaning lies in ruin. Before you none come willingly and from you shall go none Hear our prayer.

These are obliterative words, words of deathly silence, words that capture the long and painful hesitation that precedes any thought of “coming to terms”.

The device of repetition, so important in the Catholic liturgy, serves McSherry’s purposes well in Requiem. In the Kyrie, she catalogues some of the vulnerabilities and the indignities of mortally failing health:

Bed have mercy upon her Hoist have mercy upon her Catheter have mercy upon her Needle have mercy upon her…

The poet’s stern refusal to be resigned emerges in the Graduale where, for the first time, there is a marked departure from the patterned cadences of liturgical speech. The Graduale ends with a defiant declamation:

I imagine us someday sitting creased and greyed on the stoop together, rolling tobacco and reckoning the scores, but today I am here to look you in the eye, and live.

The unravelling gains momentum in the Tractus—the part of the requiem mass where an appeal is made for absolution of the souls of the “faithful departed”—a phrase which has entered common parlance and taken up residence as a glib cliché. Here we find Death wandering into a bar—a kind of departure lounge for the soon to die—where the “craic is unspooling nicely”. He arrives with little warning “but a rash of goose- / bumps and a zebra shadow casting / to the bar…”. The imagery McSherry conjures is rich with visceral unease, with portents of evil. Death is:

… all clatter and tooth, as generous with his grins as with all else…

These colourful evocations put this reviewer in mind of a passage from a short story entitled “Birth” by much-admired Canadian writer William C. McConnell, published in his collection Raise No Memorial (Orca Publishers, 2009):

“…O Death is a sly old bastard who slopes around on padded hooves and knows he can

pick the locks of doors made of happiness. He spits sparks only when it is daylight so as

not to give himself away and his ears keen the air for the tiny sounds of exhaustion so he

can slip and twist his thin-edged knife before his prey can take fright and scamper. He has

two faces, one porcine thick and baleful — that’s the one for the survivors. The other is

mellifluous, indistinct and vaguely attractive to lull the suspicions of his victims. And he

can change as fast as a chameleon in the twinkling of an eternal eye…”

In the Sequentia, McSherry steers an even wider berth around the mass’s normally solemn and orderly language, writing vividly and unsettlingly of the souls, some plainly deluded, who are gathered inside and outside the ante room/departure lounge where Death presides and continues pouring himself drinks. Here, as mentioned above, it is the infiltration of conspicuously modern terms and forms of expression that so effectively unseat the markers of orthodoxy. Here we find more than a refusal to be resigned to death; rather, McSherry spatters the page with an angered railing and flailing against death’s arbitrariness, its finality and what seem to be false balms and anodynes that are offered up to blunt its force.

…The earth and oceans vomit out the dead of sixty million years to face their Maker’s passiflora maw. He peels back the ozone layer, turns out all the stars. In darkness scrolling text appears, wrought in piercing light. It lists the sins of the world, since we were torn from mud and algae and set to worship. We close our eyes but see it scrolling still, in black on lidded red. Ellen Mullen cheated on her husband, June of nineteen ninety-four. Muhammed on the second floor stole his neighbours’ WiFi. Tor of Viken killed his father with a poisoned cup the year of the good harvest. Excuses have no meaning; all will be revealed. Look at what you just made me do. Death grimly pours another drink. Outside, the desperate corpses call on him. ‘Great Death, save us from Judgment! Death is a fountain of mercy, gives freely, and ends all. We seek he gentle ministry of worm, blowfly and beetle. From paradise we were untimely ripped.’ Others call on Christ, and prompt the Lord to promise. Even if the kid shows up, good luck finding Him in this shit-storm. The planet’s surface reddens with justice. Human, plant, and animal together scream in supplication…

In places, McSherry’s writing writhes, wraith-like on the page. It startles, it unsettles, it agonises. Its imaginative and expressive force is sufficient to provoke small gasps in the reader. In those places this long poem is both flayed and flensed.

But elsewhere the starkness of it all is leavened by flashes of clever, sardonic humour in the manner of, say Oscar Wilde—or Paul Durcan or Gavin Ewart. It is difficult to review Requiem without quoting at length from every one of its parts. If space permitted it, this reviewer would reproduce here the entirety of the Benedictus. But that is one of the longest sections so it just isn’t possible. More’s the pity. In the Benedictus, McSherry recounts Death’s arrival at her family’s house for what proved to be a long stay with periodic absences and returns. “He just / came in one day without knocking, nodded to us, / hung his hat in the hall, and left,” she tells us. We learn that the hat was, in fact, a black Borsalino and that Death hung it on a coat rack “among our / summer jackets and raincoats in kingfisher, / cream, suede, and emerald green..”. This admixture of the banal and the profound is pure alchemy. In time things go missing. Foreign objects show up unexpectedly. “The geometry of the house changed.” The Benedictus ends with McSherry’s wry appeal:

We find your intrusion at this time to be particularly inconvenient.

And when the clamour abates in Requiem, there is the tenderness. O the tenderness:

She was a sweet-voiced mahogany guitar until sickness cut her strings.

And the tender longing:

My aunts strung together rosaries to hang across the silence, as they did while Carmel died, and Brigid, Joseph, Mary, and James. Gentle lamb, who takes away the sins of the world, speak; tell us why you too are silent.

And the reverie that will be sustaining:

May you be illuminated always. Your nails were a perfect crescent moon of white on pink. Your forehead smelled like freesias when you kissed me goodnight. You starred as a young woman in My Fair Lady but I never heard you sing it. I used to think you sang too loudly in church. May an inexhaustible spotlight pick you ever out.

Síofra McSherry’s final tribute to her mother’s memory is as perfectly wrought as can be imagined. It invites comparison to Paul Muldoon’s Incantata. Emma Wright’s haunting illustrations do justice to the text. But above all, McSherry’s fierce, by turns angry and by turns tender, homage does justice to her mother’s memory. It turns an “inexhaustible spotlight” upon her, in fulfilment of McSherry’s own prayer.

There is something in Requiem for all of us who have suffered such losses, for all of us who are reluctantly accepting but (in Millay’s words) “not resigned to the shutting away of loving hearts in the hard ground”.

Brava, Síofra McSherry. A more worthy celebration of your mother’s memory cannot be conceived.

Review of Requiem – PWBridgman

25/09/2023 @ 04:22

[…] remarkable book — which appears in the English literary arts journal, London Grip — click here. And to see and hear a video recording of the talented actor and theatre director Donal O’Hanlon […]

Poems Read at the Linen Hall Library – PWBridgman

25/09/2023 @ 18:25

[…] read poems by Síofra McSherry (author of the extraordinary chapbook, Requiem, reviewed by me here) and Art Riordan (the much-celebrated Irish actor and writer). There is much gratitude here in […]