Poetry review – THE FOX’S WEDDING: Louise Warren ventures into some dark fairy-tale poems by Rebecca Hurst

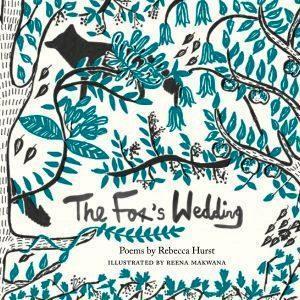

The Fox’s Wedding

Rebecca Hurst (with illustrations by Reena Makwana)

Emma Press

ISBN 9781912915958

36pp £10

The Fox’s Wedding

Rebecca Hurst (with illustrations by Reena Makwana)

Emma Press

ISBN 9781912915958

36pp £10

Not a field,

a forest.

Not a key,

a hammer.

Not a sword,

a spindle.

Not a chair,

a ladder.

Rebecca Hurst begins her deliciously dark, magical, spiky book of poems with this instructive list in the poem “The Unreliable Narrator”. Reminiscent of the fairy tale world of Angela Carter and Sisters Grimm, her collection has familiar tropes of grandmothers, forests and animal enchantments that twist and turn onto less familiar paths.

In “The Art of Needlecraft” a child walks down a path of pins exploring what shape they might take.

Once there was a child

who woke along in the forest.

Dark as it was s/he set off home

letting feet find path until at last

the path split and there were two.

These are indeed tales for a modern world. All the poems are woven through with a terrific sense of place- most of the poems are set in the Sussex Weald, where the poet grew up and where most of the poems are set. “Into the Woods” begins

This wood has a thousand exits and entrances:

stiles, gates and tripets, gaps and breaches.

This wood is hammer-pond, clay and chalybeate,

charcoal and slag heaps, leats and races.

This wood hides the boar in a thicket hemmel;

Is home to the scurry, the flindermouse, the kine.

(The title is possibly a reference to the dark fairy tale musical by Stephen Sondheim). This is such rich language, full of local folklore and words. Look them up and be inspired to visit.

Each poem in this collection casts a spell, catches you with a pin. But be careful. There are pins and needles aplenty here and some may draw blood. In “The Needle Prince”

She finds him lying a little off the path in a thicket of larch & pine,

facedown on the forest floor, his body a-bristle with needles and pins.

She finds him a little off the path. The wink of steel pinches a bite

from the gloom and prickles her eyes. She sees needles and pins.

Oh, such subversive violence here. Not necessarily in the shadows, but in the bright broad daylight of the Ashdown Forest.

In Hurst’s version of “The Frog Prince” we are back in her childhood.

On rainy nights she dances on the puddled road,

squashing worms and slugs and snails beneath

the crepe soles of her school shoes.

English rain and wetness oozes though the poem.

The Prince, when he shows, is a damp squib of a boy

from the wrong side of Tunbridge Wells.

His sodden grey cardigan droops to his knees.

Hurst knows the origins and psychology of fairy tales like the back of her hand. Numbers are magical, as are doors, golden keys, goose girls, the crone at her spindle, the cottage in the forest, the scuffed red shoes. Round and round we go with no escape, no way out. We are trapped in the spell of the tale like a spinning magic lantern show, or the play of light and shadow in the wood.

One of the most unnerving poems is “Teeth” the tale of a girl who cannot be tamed, cannot be bolted in, despite the best efforts of the hunter and his wife.

Forget her fast. Eyes shut

and split, five, six. Little bitch

little squit. Lost in the woods.

Slam and bolt the door on her.

This reminded me of Charlotte Mew’s wonderfully unsettling poem “The Farmers Bride”, except that in Hurst’s poem, the girl does not end up locked up in the attic. Instead, she is heard barking and howling, biting her way out.

Saw her scamper through the trees;

heard her calling, calling.

And heard the wild dogs

in the woods answer her call

Another animal which dominates fairy tales is of course the fox, and here he is, in full red grinning regalia in “The Animal Bridegroom”. Woe betides this poor human child ….

They say, in the apple orchard the boy hid

amongst the brambles to watch. He was found,

nabbed, dragged out, tried and spared-

thanks to the Brides pleading. ‘As she begs’,

said the Fox, ‘I’ll not rip out your throat’.

Spared from what though? And what is to be the punishment? I’ll leave you to turn the page on that one. All we can hope for is a row of stones to guide us home, but even that may be imagined.

This is a fantastically daring and assured piece of work. My only criticism is that I found the illustrations a little twee, more like the drawings in a children’s book. I would have preferred something darker. However, that one quibble aside, The Fox’s Wedding deserves to be out with your best fairy tale books. Every poem earns in place and asks to be visited again and again.

That is if you dare to.

Mar 26 2022

London Grip Poetry Review – Rebecca Hurst

Poetry review – THE FOX’S WEDDING: Louise Warren ventures into some dark fairy-tale poems by Rebecca Hurst

Rebecca Hurst begins her deliciously dark, magical, spiky book of poems with this instructive list in the poem “The Unreliable Narrator”. Reminiscent of the fairy tale world of Angela Carter and Sisters Grimm, her collection has familiar tropes of grandmothers, forests and animal enchantments that twist and turn onto less familiar paths.

In “The Art of Needlecraft” a child walks down a path of pins exploring what shape they might take.

These are indeed tales for a modern world. All the poems are woven through with a terrific sense of place- most of the poems are set in the Sussex Weald, where the poet grew up and where most of the poems are set. “Into the Woods” begins

(The title is possibly a reference to the dark fairy tale musical by Stephen Sondheim). This is such rich language, full of local folklore and words. Look them up and be inspired to visit.

Each poem in this collection casts a spell, catches you with a pin. But be careful. There are pins and needles aplenty here and some may draw blood. In “The Needle Prince”

Oh, such subversive violence here. Not necessarily in the shadows, but in the bright broad daylight of the Ashdown Forest.

In Hurst’s version of “The Frog Prince” we are back in her childhood.

English rain and wetness oozes though the poem.

Hurst knows the origins and psychology of fairy tales like the back of her hand. Numbers are magical, as are doors, golden keys, goose girls, the crone at her spindle, the cottage in the forest, the scuffed red shoes. Round and round we go with no escape, no way out. We are trapped in the spell of the tale like a spinning magic lantern show, or the play of light and shadow in the wood.

One of the most unnerving poems is “Teeth” the tale of a girl who cannot be tamed, cannot be bolted in, despite the best efforts of the hunter and his wife.

This reminded me of Charlotte Mew’s wonderfully unsettling poem “The Farmers Bride”, except that in Hurst’s poem, the girl does not end up locked up in the attic. Instead, she is heard barking and howling, biting her way out.

Another animal which dominates fairy tales is of course the fox, and here he is, in full red grinning regalia in “The Animal Bridegroom”. Woe betides this poor human child ….

Spared from what though? And what is to be the punishment? I’ll leave you to turn the page on that one. All we can hope for is a row of stones to guide us home, but even that may be imagined.

This is a fantastically daring and assured piece of work. My only criticism is that I found the illustrations a little twee, more like the drawings in a children’s book. I would have preferred something darker. However, that one quibble aside, The Fox’s Wedding deserves to be out with your best fairy tale books. Every poem earns in place and asks to be visited again and again.

That is if you dare to.