Poetry review – THE HOUSE OF EVERYTHING: James Roderick Burns walks through the John Soane museum guided by Robert Seatter’s poetry

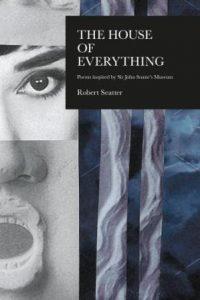

The House of Everything

Robert Seatter

Seren, 2021

ISBN 9 781781 725856

£9.99

The House of Everything

Robert Seatter

Seren, 2021

ISBN 9 781781 725856

£9.99

The House of Everything is a perfect package: beautifully produced, with just under forty poems and fifteen evocative black-and-white collages by the poet; a single-page capsule history of the London museum that inspired the work; and an introduction that, far from being prosaic (as context-settings often are), is itself poetic:

The story of [Sir John Soane] is interwoven with the stories of some of the extraordinary

objects in the house, collected from all around the world, as well as an exploration of the

impulse within us all to make material our dreams and imaginings

For the museum described, explored and reimagined is fundamentally about material reality: the things we make and live with, that shape our lives and are in turn shaped by them, the things we cherish. Soane was apparently an obsessive collector, and Robert Seatter imagines him in dialogue with the artist Michael Landy, famous for shredding and then disposing of every particle of his possessions:

Do you ever dream of what you lost?

asked John Soane,

as he walked the winding staircase

of his crammed house

touching his treasured possessions

one by one.

Do you ever dream of an empty house?

asked the other,

walking out of it,

yourself on an empty road,

carrying nothing

but the clothes on your back

listening to the sound of your breathing –

how the horizon lifts

and trembles … ?

(‘The Man who destroyed everything he had meets Sir John Soane’)

Both halves of this equation are intriguing – the latter particularly relevant in an age of irrationally high rents, as well as the widespread popularity of a book series featuring a modern day hobo who patrols America with nothing but the clothes on his back – and it is to the poet’s credit that while this dialogue occurs late in the book, it is present through almost every preceding line. Questions about the value inherent in objects, their potency and emotional charge, resonate through poem after poem:

here’s a house to banish winter,

two lion dogs at the door

to bare their teeth

and howl away time

(‘Breakfast Parlour’)

Can you hear me rattle

behind this plain wooden door?

In spite of iron rods jointing bone

to bone, tight binding of

wire, and a wedge of cork

between each countable vertebra?

(‘Skeleton in the Closet’)

Or, in an audacious piece of imagination, the poet projects Soane dreaming of the ultimate act of preservation, which oddly results in an ethereal, abstract image of permanence, rather than something concrete:

2. Make a cut to the left side of my body,

and remove all organs,

all the tasting, turning, breathing parts of me.

3. Dry them with thoroughness, till they are just so much

wrinkled bladderwrack left on the shore,

and the sea long gone beyond the horizon.

(‘Sir John Soane dreams of being mummified, in ten slow stages’)

This impulse to unpack and repack reality also runs through the book, particularly in the small boxed descriptions of each stage of the tour that run like a subtle jumbotron along the bottom of the pages, and the many versions of the thick umber light saturating the space.

However, there is a single, telling image which for me captures both Soane’s obsessive impulse to collect and preserve, and the poet’s wish to illuminate his thought, as well as describing its resulting shaping of space: that of reflection. Glasses, mirrors, water and reflective surfaces abound within the collection, as apparently they do throughout the museum. From the gift shop (“purchase a mirror/of a mirror to slip in your bag; you’ll never escape/the way light bends here”) to the famed sarcophagus of Seti I (“a moon in a skylight,/waiting for a face to be dipped in milk,/for a marble and for a mirror”); from visitors (“peering through the smoke-yellow pane”) to Soane himself (“observing his brow, its bright porcelain gleam”) – everywhere things capture light, and the human image, then reflect them back and turn us inwards in the search for meaning.

The transformative power of light reflected in an object, almost mystically spurring the internal process of reflection and consequently greater outward understanding, is captured best in a poem which explicitly addresses this idea, ‘Sir John Soane reflects on his House as a Dream’, in which the poet/collector (so deep is his understanding of Soane’s mind that the two are almost fused, one completely inhabiting the other) focuses on one prominent feature of the house – its spiral staircase, illustrated with the overlapping ridges of an ammonite – and neatly suggests the way immersion in the rising space brings heightened consciousness:

Think of it as night in every room,

then the day will surprise you,

and when you ascend the staircase

imagine floating towards the light

as if you wore a diving suit

and your breath came back to you,

cased in glass, not quite your own.

It is almost a figure of the museum (possibly all museums) itself – the act of preservation and presentation at once fencing off and removing access to the object (so Seatter’s dingy amber basement) and at the same time illuminating it, as the walker up the staircase rises into the light, seeing something for the first time, and in slightly odd circumstances, but powerfully new.

Though the book is more than a single image, one stands out above the others for its mordant wit, and the quickness with which it propels the reader to the heart of the work. Padre Giovanni, a fictional monk Soane imagined occupying a particularly gothic space in the museum, seems in constant silent dialogue with the collector, but

he never leaves

his shuttered room, the fish on his plate

watches me with its one glassy eye,

parts its dead lips, won’t speak a word.

It hardly needs to – this illuminating collection speaks for all three of them.

Feb 10 2022

London Grip Poetry Review – Robert Seatter

Poetry review – THE HOUSE OF EVERYTHING: James Roderick Burns walks through the John Soane museum guided by Robert Seatter’s poetry

The House of Everything is a perfect package: beautifully produced, with just under forty poems and fifteen evocative black-and-white collages by the poet; a single-page capsule history of the London museum that inspired the work; and an introduction that, far from being prosaic (as context-settings often are), is itself poetic:

For the museum described, explored and reimagined is fundamentally about material reality: the things we make and live with, that shape our lives and are in turn shaped by them, the things we cherish. Soane was apparently an obsessive collector, and Robert Seatter imagines him in dialogue with the artist Michael Landy, famous for shredding and then disposing of every particle of his possessions:

Do you ever dream of what you lost? asked John Soane, as he walked the winding staircase of his crammed house touching his treasured possessions one by one. Do you ever dream of an empty house? asked the other, walking out of it, yourself on an empty road, carrying nothing but the clothes on your back listening to the sound of your breathing – how the horizon lifts and trembles … ? (‘The Man who destroyed everything he had meets Sir John Soane’)Both halves of this equation are intriguing – the latter particularly relevant in an age of irrationally high rents, as well as the widespread popularity of a book series featuring a modern day hobo who patrols America with nothing but the clothes on his back – and it is to the poet’s credit that while this dialogue occurs late in the book, it is present through almost every preceding line. Questions about the value inherent in objects, their potency and emotional charge, resonate through poem after poem:

here’s a house to banish winter, two lion dogs at the door to bare their teeth and howl away time (‘Breakfast Parlour’) Can you hear me rattle behind this plain wooden door? In spite of iron rods jointing bone to bone, tight binding of wire, and a wedge of cork between each countable vertebra? (‘Skeleton in the Closet’)Or, in an audacious piece of imagination, the poet projects Soane dreaming of the ultimate act of preservation, which oddly results in an ethereal, abstract image of permanence, rather than something concrete:

2. Make a cut to the left side of my body, and remove all organs, all the tasting, turning, breathing parts of me. 3. Dry them with thoroughness, till they are just so much wrinkled bladderwrack left on the shore, and the sea long gone beyond the horizon. (‘Sir John Soane dreams of being mummified, in ten slow stages’)This impulse to unpack and repack reality also runs through the book, particularly in the small boxed descriptions of each stage of the tour that run like a subtle jumbotron along the bottom of the pages, and the many versions of the thick umber light saturating the space.

However, there is a single, telling image which for me captures both Soane’s obsessive impulse to collect and preserve, and the poet’s wish to illuminate his thought, as well as describing its resulting shaping of space: that of reflection. Glasses, mirrors, water and reflective surfaces abound within the collection, as apparently they do throughout the museum. From the gift shop (“purchase a mirror/of a mirror to slip in your bag; you’ll never escape/the way light bends here”) to the famed sarcophagus of Seti I (“a moon in a skylight,/waiting for a face to be dipped in milk,/for a marble and for a mirror”); from visitors (“peering through the smoke-yellow pane”) to Soane himself (“observing his brow, its bright porcelain gleam”) – everywhere things capture light, and the human image, then reflect them back and turn us inwards in the search for meaning.

The transformative power of light reflected in an object, almost mystically spurring the internal process of reflection and consequently greater outward understanding, is captured best in a poem which explicitly addresses this idea, ‘Sir John Soane reflects on his House as a Dream’, in which the poet/collector (so deep is his understanding of Soane’s mind that the two are almost fused, one completely inhabiting the other) focuses on one prominent feature of the house – its spiral staircase, illustrated with the overlapping ridges of an ammonite – and neatly suggests the way immersion in the rising space brings heightened consciousness:

It is almost a figure of the museum (possibly all museums) itself – the act of preservation and presentation at once fencing off and removing access to the object (so Seatter’s dingy amber basement) and at the same time illuminating it, as the walker up the staircase rises into the light, seeing something for the first time, and in slightly odd circumstances, but powerfully new.

Though the book is more than a single image, one stands out above the others for its mordant wit, and the quickness with which it propels the reader to the heart of the work. Padre Giovanni, a fictional monk Soane imagined occupying a particularly gothic space in the museum, seems in constant silent dialogue with the collector, but

It hardly needs to – this illuminating collection speaks for all three of them.