Poetry review – THIS KILT OF MANY COLOURS: James Roderick Burns investigates David Bleiman’s unusually dense pamphlet

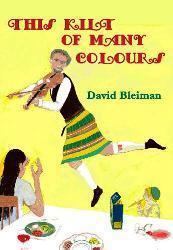

This Kilt of Many Colours

David Bleiman

Dempsey & Windle, 2021

ISBN 978-1-913-32945-7

£8.00

This Kilt of Many Colours

David Bleiman

Dempsey & Windle, 2021

ISBN 978-1-913-32945-7

£8.00

With 22 longish poems spread over three themed sections, a substantial preface, language glosses and a dedicated page of thanks, This Kilt of Many Colours – which also runs to almost fifty pages – feels much more like a collection than a pamphlet, an impression reinforced by its pleasing, clean production and high-quality perfect binding. (At £8.00 it is also on the high side for a pamphlet, but readers won’t mind this a bit once they have bought a copy for themselves.)

What seals this impression is the work: vivid, sustained and moving, marrying bittersweet experience to subtle lyricism – in four languages.

David Bleiman’s work, it seems to me, is not like anyone else’s. Drawing on the muscles and peculiarities of English, Scots, Yiddish and Spanish, it spreads over the pages at leisure, drawing in history, faith and geography, but is never less than screw-tight line by line. Take the second stanza of ‘Dream mash lullaby’, for instance, “A squeeze of honey in cinnamon milk,/a washboard singing the consonants”:

Little one, Yiddele, sleep baby, sleep

can ye no hush your greetin?

Raisins and almonds, rozhinkes mit mandeln

as the wee lambs are sleepin.

Dreams to sell, fine dreams to sell,

for you will soon be a merchant.

Sleep, our Yiddele, sleep.

Nowhere is the call to fairy-tale language heeded, but always tempered with the rough tenderness of Scots (that slight, weary tetchiness of parents – and grandparents – creeping into the lovely second line); everywhere the right word dropping like fruit around the poet’s grandchild. This command of tone, and tenderness, is repeated on the facing page, in which the concluding verse of ‘Rowan (For a September granddaughter)’ shows a similarly deft way with an English lyric:

Be deep, enchanting as a tree,

peaceful, persistent as a poem,

stand shelter, smiling at the door

and share your sparkling fruit

with all these hungry birds

who want to sing with you

the winter through.

Bleiman’s range encompasses poems of more intimate realms as well as the larger canvasses of history, such as ‘Auf Wiedersehen’, in which he contrasts his relatives’ abiding rage at Germany (“The letters from your Litvak cousins lost”, “a silent fury when/I spent my gap year in Berlin”) with his own desire to reclaim language, and experience, from totalitarianism, the process of reclamation not uncomplicated but worth the salvage on its own terms:

I will be German again:

not with a veteran’s iron cross,

not with my Stammtisch and Stein

but alone in the past where my records spin,

rescued from rupture of crystal and blood,

played out by exile and loss.

And when I return to my German home,

I’ll wear with pride the yellow patch

and gently take the needle to the dusty groove,

to The Blue Angel where the Weintraubs play,

every night when Marlene sings

from a disc in a darkened room.

It is a bravura performance. History, culture and damage – carved irreversibly into memory like grooves into vinyl – combine, despite blood and shattering loss, into culture and sensibility. It is a poem which at once challenges and accepts the past, in service of the future.

It is also impressive that Bleiman – in a pamphlet, not the usual broader and more forgiving landscape of a full collection – takes the time to explore the power of poetry itself. ‘Nasos Vayenas, 1978’ finds a copy of a biography preceding “my head stuffed with your poems”, an appreciation arriving forty years on which helps “to ensure everyday life”, but which is accompanied by lamentation: “your company another page/in my book of missed opportunities”.

But it is the extraordinary sequence of images that open the poem cold, before we have any inkling of this experience anchored in the poet’s own timeline, that leap off the page with all the energy they describe:

Like opening the oven to inspect the stew.

And your glasses steam up.

Like taking them off quickly.

And your eyebrows scald.

Like a rusty bomb, unperturbed in the estuary mud,

which now you must dive to detonate.

Here he moves from the homeliest of pictures – a man awaiting food, inconvenienced by steam – through a process of shock (ordinary steam transforming into a scalding weapon) to an image at the far end of the scale, drawn from history and warfare: unexploded ordinance, words lodged so deep in muck that we must work to set free their meaning. As an image of power masked by familiarity, or perhaps the rapid escalation of feelings that literature can bring about, and that unexpectedly, it is superb – arresting, chilling, forcing the reader to return to first understandings.

Overall, This Kilt of Many Colours affirms the unity of language and culture to be found in polyglot practice at the end of one tumultuous, awful century and the start of another (marked perhaps by heightened awareness of the pivotal role played by words in sparking cultural disputes that can rapidly degenerate into conflict?). But it does more than this. In its range of tone and meaning, from grand to tiny, the canvas of history to the smallest moments in a beloved child’s life, it shows what small black marks on pieces of paper can do – and their reach is almost infinite.

Nov 8 2021

London Grip Poetry Review – David Bleiman

Poetry review – THIS KILT OF MANY COLOURS: James Roderick Burns investigates David Bleiman’s unusually dense pamphlet

With 22 longish poems spread over three themed sections, a substantial preface, language glosses and a dedicated page of thanks, This Kilt of Many Colours – which also runs to almost fifty pages – feels much more like a collection than a pamphlet, an impression reinforced by its pleasing, clean production and high-quality perfect binding. (At £8.00 it is also on the high side for a pamphlet, but readers won’t mind this a bit once they have bought a copy for themselves.)

What seals this impression is the work: vivid, sustained and moving, marrying bittersweet experience to subtle lyricism – in four languages.

David Bleiman’s work, it seems to me, is not like anyone else’s. Drawing on the muscles and peculiarities of English, Scots, Yiddish and Spanish, it spreads over the pages at leisure, drawing in history, faith and geography, but is never less than screw-tight line by line. Take the second stanza of ‘Dream mash lullaby’, for instance, “A squeeze of honey in cinnamon milk,/a washboard singing the consonants”:

Nowhere is the call to fairy-tale language heeded, but always tempered with the rough tenderness of Scots (that slight, weary tetchiness of parents – and grandparents – creeping into the lovely second line); everywhere the right word dropping like fruit around the poet’s grandchild. This command of tone, and tenderness, is repeated on the facing page, in which the concluding verse of ‘Rowan (For a September granddaughter)’ shows a similarly deft way with an English lyric:

Bleiman’s range encompasses poems of more intimate realms as well as the larger canvasses of history, such as ‘Auf Wiedersehen’, in which he contrasts his relatives’ abiding rage at Germany (“The letters from your Litvak cousins lost”, “a silent fury when/I spent my gap year in Berlin”) with his own desire to reclaim language, and experience, from totalitarianism, the process of reclamation not uncomplicated but worth the salvage on its own terms:

It is a bravura performance. History, culture and damage – carved irreversibly into memory like grooves into vinyl – combine, despite blood and shattering loss, into culture and sensibility. It is a poem which at once challenges and accepts the past, in service of the future.

It is also impressive that Bleiman – in a pamphlet, not the usual broader and more forgiving landscape of a full collection – takes the time to explore the power of poetry itself. ‘Nasos Vayenas, 1978’ finds a copy of a biography preceding “my head stuffed with your poems”, an appreciation arriving forty years on which helps “to ensure everyday life”, but which is accompanied by lamentation: “your company another page/in my book of missed opportunities”.

But it is the extraordinary sequence of images that open the poem cold, before we have any inkling of this experience anchored in the poet’s own timeline, that leap off the page with all the energy they describe:

Here he moves from the homeliest of pictures – a man awaiting food, inconvenienced by steam – through a process of shock (ordinary steam transforming into a scalding weapon) to an image at the far end of the scale, drawn from history and warfare: unexploded ordinance, words lodged so deep in muck that we must work to set free their meaning. As an image of power masked by familiarity, or perhaps the rapid escalation of feelings that literature can bring about, and that unexpectedly, it is superb – arresting, chilling, forcing the reader to return to first understandings.

Overall, This Kilt of Many Colours affirms the unity of language and culture to be found in polyglot practice at the end of one tumultuous, awful century and the start of another (marked perhaps by heightened awareness of the pivotal role played by words in sparking cultural disputes that can rapidly degenerate into conflict?). But it does more than this. In its range of tone and meaning, from grand to tiny, the canvas of history to the smallest moments in a beloved child’s life, it shows what small black marks on pieces of paper can do – and their reach is almost infinite.