Poetry review – 100 POEMS TO SAVE THE EARTH: Alwyn Marriage reviews a new anthology edited by Zoë Brigley & Kristian Evans

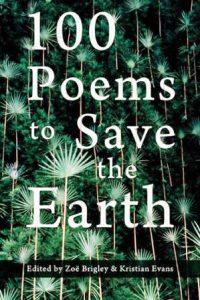

100 Poems to Save the Earth

edited by Zoë Brigley and Kristian Evans

Seren Books, 2021

ISBN 9 781781 726242

143 pp £12.99

100 Poems to Save the Earth

edited by Zoë Brigley and Kristian Evans

Seren Books, 2021

ISBN 9 781781 726242

143 pp £12.99

Reviewing an anthology is, by its nature, bound to be rather different from reviewing an individual collection. While it is necessary, when considering the work of one poet, to consider the coherence and shape of the book, the place of the poet within the canon, the truth and integrity of the subject matter and the development of the poet since earlier work, the major consideration is, naturally, the overall quality of the poetry.

The requirements for a review of an anthology are subtly different. For a start, work by very different poets is likely to vary in quality; and some poems are bound to fit more neatly into the chosen theme than others. It even seems a little invidious to single out a few poems for comment, as that necessitates omitting to mention scores of others that are probably just as worthy. This particular anthology contains poems by a number of well-known poets, alongside others by relative new-comers, and that is to be applauded; but it might possibly make the ride through the collection a little bumpier than might be expected.

So what criteria should one use in reviewing an anthology?

One question that is worth asking, particularly, perhaps, in this case, is: does the poetry selection justify the title of the book? 100 Poems to Save the Earth is nothing if not ambitious. There are no ifs or buts, no gentle suggestion that the collection might have just a tiny part to play in saving the planet, no desire to support those acting on our behalf in their efforts to address climate change. Every reader knows, of course, that the collection, inspiring as it may be, cannot do very much even to slightly alleviate the dire straits we are in. However, perhaps poetic licence will allow the title to stand, reminding us of the need to find new and dramatic ways to come together to try to save the earth – or, rather, to save the human race: the earth will probably get along fine if it loses us, but the future of humanity is in severe danger.

In order to satisfy the title, one would expect to find poems of warning, celebration and fear; and such poems do occur in the anthology. Owen Sheer’s “Liable to Floods”, which relates a flood bearing away an army camp, is clearly a metaphor for much more than that, and is a vivid warning of what much of planet Earth is likely to face now and in the future.

Given the precarious state we find ourselves in, it is not surprising that there is, in this collection, more warning than celebration. But there are positive poems too, including Mimi Khalvati’s delightful sonnet, “Eggs”. After reading this poem, one understands more of what an egg truly is. And this simplicity of responding in celebration can be found in other poems, such as “September” by Jennifer Hunt:

Now, with my colander,

by the open kitchen door,

the sun makes a square on the red lino.

Outside, white hens peck at shreds of light.

In order to celebrate the Earth, one must also learn to see clearly; and Kei Miller, in “To know green from green”, drives a clean scalpel between some of the various shades that we sometimes forget to differentiate as we label them all green:

You must know emerald different from jade; know greens that travel

towards grey – laurel, artichoke, sage. Forest is different from jungle

is different from tree which is itself a shade of green.

Fear is slightly different from warning. It is what follows on when we fully realise the gravity of the warnings we have received. Ros Cogan, in “Ragnarök”, moves us on from warning to fear:

A one-eyed man will pull on his broad-brimmed hat

and stalk away. Please don't expect a warning.

This is a whimper not a bang, but it's

a whimper that

will level hills and drown the suffering world.

However, at the end of the day, what one wants from a book entitled 100 Poems to Save the Earth is hope. And we are not denied that in this collection. To name but two examples, the well-known “The Peace of Wild Things” by Wendell Berry, with its prescription for what we should do if we wake in the night in terror of what is to come, for ourselves and our children:

I go and lie down where the wood drake

rests in his beauty on the water, and the great heron feeds.

I come into the peace of wild things

who do not tax their lives with forethought

of grief. I come into the presence of still water.

And I feel above me the day-blind stars

waiting with their light. For a time

I rest in the grace of the world, and am free.

The poems of true hope are, unsurprisingly, in rather short supply. But then, the fact that there are 100 poems here wanting to save the earth is, in itself, a glimmer of hope. And, of course, this anthology is in no way comprehensive. Thousands of poets all over the world are loving the earth and creating poetry to celebrate and, if possible, sustain it. Sometimes this is through dramatic poems warning us of what humanity is doing to the earth, and sometimes in quieter and more modest ways, as Grahame Davies points out in “Prayer”: ‘In unremembered quiet words / that keep a soul on the path‘.

There are, of course, many more poems in this anthology that are worthy of mention and that I’d like to quote in full. These include “When you touch me I am a wind turbine” by Liz Berry and “Seabird’s Blessing” by Alice Oswald.

Leaving the individual poems aside, it is possible to look at how well the book works as an anthology. Factors here include selection, layout, editing and overall shape. The editors have attempted to be inclusive in their selection, though any choice of what to include is bound to have limitations and there will always be poems and/or poets that others would have chosen. The gentle emergence of themes through the book, such as fish, birds, bees and honey, is satisfying; and the general layout is good. The only exception I would make on this score is the same criticism I have made in other reviews, which is that, unless it is absolutely unavoidable, I consider it bad practice to have two-page poems going overleaf, as it diminishes the enjoyment for the reader if she gets to the bottom of the first page without knowing whether that is the end or not. I hesitate to raise this yet again, but it is such a fundamental aspect of the enjoyment of reading poetry; and making the effort to keep two-page poems on facing pages shows more respect for the reader.

Nov 14 2021

100 Poems to Save the Earth

Poetry review – 100 POEMS TO SAVE THE EARTH: Alwyn Marriage reviews a new anthology edited by Zoë Brigley & Kristian Evans

Reviewing an anthology is, by its nature, bound to be rather different from reviewing an individual collection. While it is necessary, when considering the work of one poet, to consider the coherence and shape of the book, the place of the poet within the canon, the truth and integrity of the subject matter and the development of the poet since earlier work, the major consideration is, naturally, the overall quality of the poetry.

The requirements for a review of an anthology are subtly different. For a start, work by very different poets is likely to vary in quality; and some poems are bound to fit more neatly into the chosen theme than others. It even seems a little invidious to single out a few poems for comment, as that necessitates omitting to mention scores of others that are probably just as worthy. This particular anthology contains poems by a number of well-known poets, alongside others by relative new-comers, and that is to be applauded; but it might possibly make the ride through the collection a little bumpier than might be expected.

So what criteria should one use in reviewing an anthology?

One question that is worth asking, particularly, perhaps, in this case, is: does the poetry selection justify the title of the book? 100 Poems to Save the Earth is nothing if not ambitious. There are no ifs or buts, no gentle suggestion that the collection might have just a tiny part to play in saving the planet, no desire to support those acting on our behalf in their efforts to address climate change. Every reader knows, of course, that the collection, inspiring as it may be, cannot do very much even to slightly alleviate the dire straits we are in. However, perhaps poetic licence will allow the title to stand, reminding us of the need to find new and dramatic ways to come together to try to save the earth – or, rather, to save the human race: the earth will probably get along fine if it loses us, but the future of humanity is in severe danger.

In order to satisfy the title, one would expect to find poems of warning, celebration and fear; and such poems do occur in the anthology. Owen Sheer’s “Liable to Floods”, which relates a flood bearing away an army camp, is clearly a metaphor for much more than that, and is a vivid warning of what much of planet Earth is likely to face now and in the future.

Given the precarious state we find ourselves in, it is not surprising that there is, in this collection, more warning than celebration. But there are positive poems too, including Mimi Khalvati’s delightful sonnet, “Eggs”. After reading this poem, one understands more of what an egg truly is. And this simplicity of responding in celebration can be found in other poems, such as “September” by Jennifer Hunt:

In order to celebrate the Earth, one must also learn to see clearly; and Kei Miller, in “To know green from green”, drives a clean scalpel between some of the various shades that we sometimes forget to differentiate as we label them all green:

Fear is slightly different from warning. It is what follows on when we fully realise the gravity of the warnings we have received. Ros Cogan, in “Ragnarök”, moves us on from warning to fear:

However, at the end of the day, what one wants from a book entitled 100 Poems to Save the Earth is hope. And we are not denied that in this collection. To name but two examples, the well-known “The Peace of Wild Things” by Wendell Berry, with its prescription for what we should do if we wake in the night in terror of what is to come, for ourselves and our children:

The poems of true hope are, unsurprisingly, in rather short supply. But then, the fact that there are 100 poems here wanting to save the earth is, in itself, a glimmer of hope. And, of course, this anthology is in no way comprehensive. Thousands of poets all over the world are loving the earth and creating poetry to celebrate and, if possible, sustain it. Sometimes this is through dramatic poems warning us of what humanity is doing to the earth, and sometimes in quieter and more modest ways, as Grahame Davies points out in “Prayer”: ‘In unremembered quiet words / that keep a soul on the path‘.

There are, of course, many more poems in this anthology that are worthy of mention and that I’d like to quote in full. These include “When you touch me I am a wind turbine” by Liz Berry and “Seabird’s Blessing” by Alice Oswald.

Leaving the individual poems aside, it is possible to look at how well the book works as an anthology. Factors here include selection, layout, editing and overall shape. The editors have attempted to be inclusive in their selection, though any choice of what to include is bound to have limitations and there will always be poems and/or poets that others would have chosen. The gentle emergence of themes through the book, such as fish, birds, bees and honey, is satisfying; and the general layout is good. The only exception I would make on this score is the same criticism I have made in other reviews, which is that, unless it is absolutely unavoidable, I consider it bad practice to have two-page poems going overleaf, as it diminishes the enjoyment for the reader if she gets to the bottom of the first page without knowing whether that is the end or not. I hesitate to raise this yet again, but it is such a fundamental aspect of the enjoyment of reading poetry; and making the effort to keep two-page poems on facing pages shows more respect for the reader.