Poetry review – THE TASTE OF STEEL / THE SMELL OF SNOW: Edmund Prestwich explores a double volume of poems by Danish poet Pia Tafdrup (translated by David McDuff)

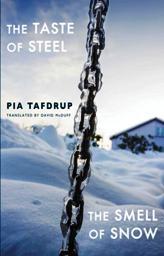

The Taste of Steel / The Smell of Snow

Pia Tafdrup, translated by David McDuff

Bloodaxe Books

ISBN 978-1-78037-504-5

192pp £12.99

The Taste of Steel / The Smell of Snow

Pia Tafdrup, translated by David McDuff

Bloodaxe Books

ISBN 978-1-78037-504-5

192pp £12.99

Pia Tafdrup is apparently a leading and highly prolific Danish poet. I read her for the first time to write this review, and I’ve only read the two books brought together in this volume, so what I say about her will reflect the impressions of a new and partial reader. I’ll be particularly concerned with qualities that make for the success or failure of individual poems. Readers who know all her work may have a different perspective. For example, I know that The Taste of Steel and The Smell of Snow are just the first of a projected series of five themed collections focusing on the different senses (four have apparently been completed in Danish). Presumably their ideal reader would be able to read each in the light of a thorough and intimate knowledge of the others.

My first broad observation is that reading the two books through I found it hard to maintain momentum in the first and very easy in the second. In the first, I did enjoy the clarity and force of imagery, description and scene-building, and found many lines that, taken on their own, had the beauty and phonetic expressiveness of ‘A flock of swans on the water floats in light’ at the start of “Stopping at the Sight of Swans”. However, looking at whole poems, I repeatedly felt that their expressiveness in other ways was being undermined by what to me was a strange inertness in their movement. Instead of syntax, metre, the cadence of lines and the gear changes of line endings coming together to animate the unfolding of the poem’s thought, I felt they left the words lying limp on the page. I know that this aspect of poetry doesn’t have the same importance for everyone, and of course I recognize that I might be failing to see an expressiveness in the movement of a given passage that’s perfectly obvious to other people, so I’ll quote a bit more of “Stopping at the Sight of Swans” to let readers form their own judgement:

A flock of swans on the water floats in light,

rocked forward by a breeze

that ruffles the lake in the middle of town.

The salt of your words

so unexpectedly rubbed into my wound.

The swans depart in a swoop across the lake,

rise all of a sudden,

take off heavily in a gathered flock.

What powers want the birds to go up

above the water’s surface, when they have a lake

of fish-shoals, galaxies of green seaweed?

To my mind, the supreme power of lyric writing is to make the reader not merely see something but almost physically feel it. Here, the first line does make me almost feel I’m becoming the swans floating in light when I read the last three words. When something like that happens, the movement of the words embodies the movement of the poet’s mind and makes the reader become one with it. However, in the lines that follow, the incompleteness of the second sentence and the inertness of most of the line endings seem to me to kill that kind of embodiment. I like the images – despite the way the book’s title focuses on taste, Tafdrup’s powerfully visual imagination is thankfully very much in evidence – and some individual phrases have a rich auditory expressiveness, like ‘galaxies of green seaweed”’, but the continuity of embodiment is gone. Clear and vivid though they are, it’s as if the poems of The Taste of Steel haven’t come quite fully alive as poetry in English. There’s a sense of seeing them a little blurrily and at a remove. This is hardly surprising in translations. What is remarkable is how much the poems of The Smell of Snow escape this problem. English might almost have been their original language. At the same time, part of the joy of reading them comes from their abiding strangeness of viewpoint and sensibility.

Five I particularly liked were those in the fifth section of The Smell of Snow, “The five seasons. A catalogue of smells”. “Spring” is the first, beginning

Smell of melted ice and light that dazzles white,

of sea-cold wind that streams over land, of sun

that fills the vapour-heavy air, smell of wet fields,

smell of snowdrops, of winter aconite, crocus, coltsfoot and violet

locally anaesthetises the air here, as the bush full of sparrows

initiates the day with an undecipherable song,

smell of dust from pollen, of half a ton of freshly-turned

earth in the form of shots from mole, subterranean,

yet also perceptible firework display for the nose ...

‘Locally anaesthetises’ seems to me a jarring misstep in terms of language, though the idea makes strong sense in terms of the way the poem contrasts different experiences and times. In other ways, this is superb. Though the accumulation of sensuous detail is almost overwhelming, the incantatory rhythm and the forward push given by the repetitions of ‘smell’ carry you through with a drive that brings together details that might otherwise have flown apart. The strength of this centripetal drive allows Tafdrup’s translator McDuff to create voluptuous little islands of mirrored sound around some of the images (‘Smell of melted ice’, ‘light that dazzles white’ and so on), encouraging us to linger briefly without dissipating the forward momentum.

The fifth stanza introduces a sudden note of unhappiness. Several things give it bite: the sharpness of the physical image, the abrupt way it contradicts the previously prevailing mood, suggesting how completely spring can fail to bring healing for some people, and finally the way it gives a tantalizingly undeveloped glimpse of a whole backstory and life situation:

smell of tender green leaves and at the same time my mother’s

melancholy, as her nails scratch dirt from the glass pane ...

Subsequent stanzas expand on different kinds of resistance to the wakening of new life in spring. Some of these are psychological, emotional, intellectual –

inscrutable

moments wash in and drive home like a mighty swell,

smell of burnt bridges, of shipwrecks and new abysses

to go plunging down, as we dive quietly into each other ...

Others are immediate, concrete and literal images of smells which are at the same time symbolically resonant:

smell of wet stains, plaster that decays, crumbles

like old skin peeling off in long flakes ...

The wide reflections and the specific details give life to each other, and the form powerfully gives life to both. When Tafdrup says ‘moments wash in and drive home like a mighty swell’, what embodies that swell is the power of rhythm and syntax, the huge, swelling force of the poem’s single, thirty-three line sentence.

I’ve spent a long time on “Spring” because it typifies what to me is the great strength of the best of the poems, the way they present very concrete moments of experience, and leave interpretation and reflection in the freedom of the reader. This applies to moral and social issues and also to the autobiographical strands that are woven through many of the poems. Some of the poems I find weaker develop such reflections with an explicitness that some readers will like, and that probably works well in public readings, but that I find both leaves and gives too little to my own imagination and even, in a few cases, risks triteness. I prefer a lighter, more tangential handling of such matters, as we find in another stanza of “Spring”:

smell of coffee in cafés filled with guests wrapped in blankets,

while a boy in the sun goes from table to table, begging ...

It’s easy to imagine how a weaker poet might have let a moral-political point usurp the poem with crude, buttonholing insistence. Tafdrup lets the beggar’s presence and its possible implications flicker in our minds, making a deeper impact by inviting us to reflect on it for ourselves. By a skilful touch she has the boy ‘in the sun’, thereby participating in the life of spring at least at this point, so that we think for ourselves how much worse it might be for him at other times.

I’ve avoided writing about “Summer”, the next poem in the group, because although I think that it’s even better and extremely powerful I would have had to write about it at much greater length.

Aug 28 2021

London Grip Poetry Review – Pia Tafdrup

Poetry review – THE TASTE OF STEEL / THE SMELL OF SNOW: Edmund Prestwich explores a double volume of poems by Danish poet Pia Tafdrup (translated by David McDuff)

Pia Tafdrup is apparently a leading and highly prolific Danish poet. I read her for the first time to write this review, and I’ve only read the two books brought together in this volume, so what I say about her will reflect the impressions of a new and partial reader. I’ll be particularly concerned with qualities that make for the success or failure of individual poems. Readers who know all her work may have a different perspective. For example, I know that The Taste of Steel and The Smell of Snow are just the first of a projected series of five themed collections focusing on the different senses (four have apparently been completed in Danish). Presumably their ideal reader would be able to read each in the light of a thorough and intimate knowledge of the others.

My first broad observation is that reading the two books through I found it hard to maintain momentum in the first and very easy in the second. In the first, I did enjoy the clarity and force of imagery, description and scene-building, and found many lines that, taken on their own, had the beauty and phonetic expressiveness of ‘A flock of swans on the water floats in light’ at the start of “Stopping at the Sight of Swans”. However, looking at whole poems, I repeatedly felt that their expressiveness in other ways was being undermined by what to me was a strange inertness in their movement. Instead of syntax, metre, the cadence of lines and the gear changes of line endings coming together to animate the unfolding of the poem’s thought, I felt they left the words lying limp on the page. I know that this aspect of poetry doesn’t have the same importance for everyone, and of course I recognize that I might be failing to see an expressiveness in the movement of a given passage that’s perfectly obvious to other people, so I’ll quote a bit more of “Stopping at the Sight of Swans” to let readers form their own judgement:

To my mind, the supreme power of lyric writing is to make the reader not merely see something but almost physically feel it. Here, the first line does make me almost feel I’m becoming the swans floating in light when I read the last three words. When something like that happens, the movement of the words embodies the movement of the poet’s mind and makes the reader become one with it. However, in the lines that follow, the incompleteness of the second sentence and the inertness of most of the line endings seem to me to kill that kind of embodiment. I like the images – despite the way the book’s title focuses on taste, Tafdrup’s powerfully visual imagination is thankfully very much in evidence – and some individual phrases have a rich auditory expressiveness, like ‘galaxies of green seaweed”’, but the continuity of embodiment is gone. Clear and vivid though they are, it’s as if the poems of The Taste of Steel haven’t come quite fully alive as poetry in English. There’s a sense of seeing them a little blurrily and at a remove. This is hardly surprising in translations. What is remarkable is how much the poems of The Smell of Snow escape this problem. English might almost have been their original language. At the same time, part of the joy of reading them comes from their abiding strangeness of viewpoint and sensibility.

Five I particularly liked were those in the fifth section of The Smell of Snow, “The five seasons. A catalogue of smells”. “Spring” is the first, beginning

‘Locally anaesthetises’ seems to me a jarring misstep in terms of language, though the idea makes strong sense in terms of the way the poem contrasts different experiences and times. In other ways, this is superb. Though the accumulation of sensuous detail is almost overwhelming, the incantatory rhythm and the forward push given by the repetitions of ‘smell’ carry you through with a drive that brings together details that might otherwise have flown apart. The strength of this centripetal drive allows Tafdrup’s translator McDuff to create voluptuous little islands of mirrored sound around some of the images (‘Smell of melted ice’, ‘light that dazzles white’ and so on), encouraging us to linger briefly without dissipating the forward momentum.

The fifth stanza introduces a sudden note of unhappiness. Several things give it bite: the sharpness of the physical image, the abrupt way it contradicts the previously prevailing mood, suggesting how completely spring can fail to bring healing for some people, and finally the way it gives a tantalizingly undeveloped glimpse of a whole backstory and life situation:

Subsequent stanzas expand on different kinds of resistance to the wakening of new life in spring. Some of these are psychological, emotional, intellectual –

Others are immediate, concrete and literal images of smells which are at the same time symbolically resonant:

The wide reflections and the specific details give life to each other, and the form powerfully gives life to both. When Tafdrup says ‘moments wash in and drive home like a mighty swell’, what embodies that swell is the power of rhythm and syntax, the huge, swelling force of the poem’s single, thirty-three line sentence.

I’ve spent a long time on “Spring” because it typifies what to me is the great strength of the best of the poems, the way they present very concrete moments of experience, and leave interpretation and reflection in the freedom of the reader. This applies to moral and social issues and also to the autobiographical strands that are woven through many of the poems. Some of the poems I find weaker develop such reflections with an explicitness that some readers will like, and that probably works well in public readings, but that I find both leaves and gives too little to my own imagination and even, in a few cases, risks triteness. I prefer a lighter, more tangential handling of such matters, as we find in another stanza of “Spring”:

It’s easy to imagine how a weaker poet might have let a moral-political point usurp the poem with crude, buttonholing insistence. Tafdrup lets the beggar’s presence and its possible implications flicker in our minds, making a deeper impact by inviting us to reflect on it for ourselves. By a skilful touch she has the boy ‘in the sun’, thereby participating in the life of spring at least at this point, so that we think for ourselves how much worse it might be for him at other times.

I’ve avoided writing about “Summer”, the next poem in the group, because although I think that it’s even better and extremely powerful I would have had to write about it at much greater length.