Poetry review – KARAOKE KING: Kate Ashton admires the range and complexity of Dai George’s new collection

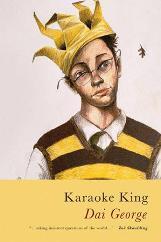

Karaoke King

Dai George

Seren, 2021

ISBN 978-1-78172-628-0

£9.99

Karaoke King

Dai George

Seren, 2021

ISBN 978-1-78172-628-0

£9.99

Anyone else who failed to follow up on a sometime passion for Bob Marley should get tuned back in to reggae, starting with Gregory Isaacs whose vocal tone has been somewhere described as one of ‘pained purity’. Dai George is a fan. He must have a good ear for a sibling soul.

The poems of George’s new collection, Karaoke King, are nothing less than transcendent. No tricksy stuff here. Just lucidity and formal grace; the words and the music. Their ability to move us to tears, to laughter, or contemplation of the mess we make of the world, and its extraordinary capacity for forgiveness, offering fresh opportunities for redemption.

Permeating the work is a profound preoccupation with love, embracing all colours, persuasions and proximities and patterned on the sacred. Extending from this is an exploration of lack, exile and exclusion: the plight of the outsider. And then comes the narrative of learning love, the trajectory from childhood towards some level of maturity… ‘when the Buldingsroman flops/exhausted on the other side of innocence’ (“Party Time”).

The opening poem of the book’s first section, “Doxology”, modelled on a prayer of thanks, describes the healing response to natural beauty constantly impinged upon and distorted by human anxiety: ‘Blessings flow, but trouble finds me/in the impasse after rain.’ How short is our attention span! How perversely we reject consolation, distract ourselves from quietude and gratitude by

The parliament still warring

through its agonies of choice,

the hustle never ending

nor the trouble nor the joy.

A politician’s voice harries the poet, damning his lack of productivity while he wanders through “The Park in the Afternoon”:

I see his point. Diverse and splendid

things have brought us here, we heathens

in the Christendom to come. The drunk.

the retired, the roistering lads

bunking off early with blazer sleeves

riding up their arms – each of us

truant and gentle for an hour,

our output no more than

what we can make

of the angle of

hurried daylight before

a shower.

And ominous, omnipresent, there is an awareness of climate change,

The weather’s been a ruined party now for years.

It mugs and flatters, grinding through its old

routine while drifting out of key

…. It’s warmer now, but sicklier and wearied.

[“Fooled Evening”]

There’s a horrified recoil from present reality. ‘I have only ever lived among pollution. Tell me it is not the sky I look at but an irradiated blanket’, (“Universal Access”). George’s childhood world of ‘invented tribes…kaleidoscopic cultures’ has given way to ‘the promise of a never spent or perfected flux… ‘which keeps the poet tethered to the city. He feels the moorings slip; he must become a man, and in the world as it is now, “Far Enough Away”:

You mistake me for flesh: for the honest captain

who can follow where the cruising stars have signalled,

glittering and keen. My body isn’t like that.

It remembers water, remembers it too well

when you come near, but returns each night

to settled pastures, indentured groves, the landlocked

love that doesn’t think to guard or name its territories.

“Near Historical Swoon” holds intimations of immortality extraordinarily deeply felt:

Watching from afar,

I thought that spring would hold, and save me from the man

I was: a homebound drifter shuffling laps around the park,

his government embroiled in vested sleaze, all hopes for what

he’d come to be not far removed from what would pass,

but far enough the deficit will make him swoon.

But he’s firmly on the road to redemption. Dylan Thomas boogies his way through “Karaoke King” and George takes up the baton and the beat from his wild Welsh forerunner: ‘Iambic I am,/real dolorous and rusty, and my chanson/brings the house down to an empty bar…

Here they are,

the ruddy legends – all yr butties dressed in tuxes on the

pitchside of yr dreams. Belting out unchappelled hymns

with boiled-ham patriotic breath, their brigadier goat.

Bethesda and Moriah, I have known thy deacons! I lay

down beneath their corrugated roofs and raged

raged raged against the dying of the greener grass.

Magical!

The threshold’s crossed in the collection’s second section, “From a History of Jamaican Music”; there are choices to be made on the way to manhood, nerves overcome, a voice to be found and heard…‘Songwriters will understand – the void/before a melody arrives, when breath/can’t seem to shape it’, (“Referendum Calypso”). But then he’s off, quoting Lloyd Bradley’s words from Bass Culture: When Reggae Was King… ‘the sound system had been created by and for Jamaica’s dispossessed’, and the poet declares ‘Which is where I first come in/feeling dispossessed somehow/at 18.’

Epiphany arrives on the “Bus to Skaville”… ‘An idiot weekend, balanced on my boyhood’s edge/like a pint of squash atop a mantelpiece.’ He’s upstairs on a northbound number 23 from town, nursing ‘a bootless thought for Ellie Glynn’ while downstairs it’s all ‘Dai caps, canes,/shopping for the week and summer coats’, and he plugs in his earbuds to blot it all out, tuning in to his newest acquisition… ‘Till now all songs have jangled through the unrequited treble’, but this disc, its burgundy box

sporting a horse with a Trojan plume –

goes chick-a-boom and canters through my mind

as if the cover pic were being whipped...

and

a heat comes down; a newly gifted knack

for walking with a naughty strut...

Time’s up for Ellie and her kin, “People Rocksteady”:

Better get ready girl, your boy

is coming and he’s learned the way

to syncopate and shake his head –

he isn’t saying no. Though born

a loser, he scrubs up fine – his

steps have cooled to gladness.

From here the collection opens out into the wide world; poems pulsing with a universal sense of injury and injustice for the wounds we cause and bear, especially for victims of tyranny – the poor, the oppressed, those with the ‘wrong’ colour skin. In the measured prose poem “Soon Forward” – taking its title from a song by Gregory Isaacs – George describes his Welsh background and upbringing embracing close family and community ties, socialism and Amnesty International. It tells how his father helped a Kurdish asylum-seeker to fill in his claim form, but the application failed and they never heard from him again… Another Isaacs song gives George the words he needs: ‘You could say that home was as open as a door – a door you could nudge and step inside, if you knew it wasn’t locked.’

The formally fragmented “Or, A Windrush Interlude” is an agonised protest against white romanticism of Black ‘cool’: the excruciating demand that a ‘character’ in beanie and fingerless mittens on Blackstock Road provide a rendering of No Woman No Cry, when the only thing he’s received from woman that week is a ‘no’ to his citizenship claim.

A summer party, and in “Soon Forward”the poet watches someone put on the Isaacs track:

Soon forward, come turn me on yeah

My whiteness draws nearer, tiptoeing round the garden. Nervously at first it

shows itself, or what I mean is, for the first time I can see it [...]The whiteness

you know in Berkshire, which makes you feel like you’re being watched. The

whiteness your mother calls not being served, and I presume myself above.

This last line just about the most tender, abject, shaming and memorable I’ve read on the entire subject.

“Party Time” an elegy for the Jamaican musician Slim Smith, leads most presciently into the third and final section of the book, ‘September’s Child’, where in “Sun Has Spoken”, the poet contemplates lost love. And lost innocence in “Poem in which my hairline recedes”, where Bruce Springsteen stars as the epitome of high attainment, having written Born to Run at the age of only 25…

his album of awakening and fear

at the chances hurtling past on the irretrievable highway

Christ I can’t stop staring at those deathless gatefold shots

where leather-jacketed he beams and leans on Clarence

man cleavage and medallion on show

as he sings to Mary

and explains how they’ve got one last chance to

make it real

America morphs world-stoppingly in “Post-historical Teatime” from the boyhood dream engendered by a ruby lounger on the pool in TV’s ‘neighbours neighbours’ and sleek silver aluminium tins of coke ‘stocked by Ben’s mum in her fridge’, when walking back from school he and his friend’s shared headphones are yanked off by another boy who tells them ‘some nutter nuked America/while we were still in period 6’. “New York Morning, Six Years On” takes a wry look at the metropolis ‘that turns routine commutes into a high/stakes hockey match’, where MoMA spits him out, hyperventilating, overdosed on postmodernism on Fifth,

where Trump

Tower grins through the morning. Bathed in a glancing

plutocratic sun, I feel like I’ll never stop falling. The city

swarms over me, crackle and dirt, a pitiless grinding signal.

It doesn’t love me or help me up. It pulps me to beef on its griddle.

The collection’s closing pastoral, “Pink Cones”, brings us back full circle… ‘The door will open on a different garden,/air more intimate and careful in its reach’.

A surefooted homecoming.

Aug 18 2021

London Grip Poetry Review – Dai George

Poetry review – KARAOKE KING: Kate Ashton admires the range and complexity of Dai George’s new collection

Anyone else who failed to follow up on a sometime passion for Bob Marley should get tuned back in to reggae, starting with Gregory Isaacs whose vocal tone has been somewhere described as one of ‘pained purity’. Dai George is a fan. He must have a good ear for a sibling soul.

The poems of George’s new collection, Karaoke King, are nothing less than transcendent. No tricksy stuff here. Just lucidity and formal grace; the words and the music. Their ability to move us to tears, to laughter, or contemplation of the mess we make of the world, and its extraordinary capacity for forgiveness, offering fresh opportunities for redemption.

Permeating the work is a profound preoccupation with love, embracing all colours, persuasions and proximities and patterned on the sacred. Extending from this is an exploration of lack, exile and exclusion: the plight of the outsider. And then comes the narrative of learning love, the trajectory from childhood towards some level of maturity… ‘when the Buldingsroman flops/exhausted on the other side of innocence’ (“Party Time”).

The opening poem of the book’s first section, “Doxology”, modelled on a prayer of thanks, describes the healing response to natural beauty constantly impinged upon and distorted by human anxiety: ‘Blessings flow, but trouble finds me/in the impasse after rain.’ How short is our attention span! How perversely we reject consolation, distract ourselves from quietude and gratitude by

The parliament still warring through its agonies of choice, the hustle never ending nor the trouble nor the joy.A politician’s voice harries the poet, damning his lack of productivity while he wanders through “The Park in the Afternoon”:

And ominous, omnipresent, there is an awareness of climate change,

The weather’s been a ruined party now for years. It mugs and flatters, grinding through its old routine while drifting out of key …. It’s warmer now, but sicklier and wearied. [“Fooled Evening”]There’s a horrified recoil from present reality. ‘I have only ever lived among pollution. Tell me it is not the sky I look at but an irradiated blanket’, (“Universal Access”). George’s childhood world of ‘invented tribes…kaleidoscopic cultures’ has given way to ‘the promise of a never spent or perfected flux… ‘which keeps the poet tethered to the city. He feels the moorings slip; he must become a man, and in the world as it is now, “Far Enough Away”:

“Near Historical Swoon” holds intimations of immortality extraordinarily deeply felt:

But he’s firmly on the road to redemption. Dylan Thomas boogies his way through “Karaoke King” and George takes up the baton and the beat from his wild Welsh forerunner: ‘Iambic I am,/real dolorous and rusty, and my chanson/brings the house down to an empty bar…

Magical!

The threshold’s crossed in the collection’s second section, “From a History of Jamaican Music”; there are choices to be made on the way to manhood, nerves overcome, a voice to be found and heard…‘Songwriters will understand – the void/before a melody arrives, when breath/can’t seem to shape it’, (“Referendum Calypso”). But then he’s off, quoting Lloyd Bradley’s words from Bass Culture: When Reggae Was King… ‘the sound system had been created by and for Jamaica’s dispossessed’, and the poet declares ‘Which is where I first come in/feeling dispossessed somehow/at 18.’

Epiphany arrives on the “Bus to Skaville”… ‘An idiot weekend, balanced on my boyhood’s edge/like a pint of squash atop a mantelpiece.’ He’s upstairs on a northbound number 23 from town, nursing ‘a bootless thought for Ellie Glynn’ while downstairs it’s all ‘Dai caps, canes,/shopping for the week and summer coats’, and he plugs in his earbuds to blot it all out, tuning in to his newest acquisition… ‘Till now all songs have jangled through the unrequited treble’, but this disc, its burgundy box

and

Time’s up for Ellie and her kin, “People Rocksteady”:

From here the collection opens out into the wide world; poems pulsing with a universal sense of injury and injustice for the wounds we cause and bear, especially for victims of tyranny – the poor, the oppressed, those with the ‘wrong’ colour skin. In the measured prose poem “Soon Forward” – taking its title from a song by Gregory Isaacs – George describes his Welsh background and upbringing embracing close family and community ties, socialism and Amnesty International. It tells how his father helped a Kurdish asylum-seeker to fill in his claim form, but the application failed and they never heard from him again… Another Isaacs song gives George the words he needs: ‘You could say that home was as open as a door – a door you could nudge and step inside, if you knew it wasn’t locked.’

The formally fragmented “Or, A Windrush Interlude” is an agonised protest against white romanticism of Black ‘cool’: the excruciating demand that a ‘character’ in beanie and fingerless mittens on Blackstock Road provide a rendering of No Woman No Cry, when the only thing he’s received from woman that week is a ‘no’ to his citizenship claim.

A summer party, and in “Soon Forward”the poet watches someone put on the Isaacs track:

This last line just about the most tender, abject, shaming and memorable I’ve read on the entire subject.

“Party Time” an elegy for the Jamaican musician Slim Smith, leads most presciently into the third and final section of the book, ‘September’s Child’, where in “Sun Has Spoken”, the poet contemplates lost love. And lost innocence in “Poem in which my hairline recedes”, where Bruce Springsteen stars as the epitome of high attainment, having written Born to Run at the age of only 25…

America morphs world-stoppingly in “Post-historical Teatime” from the boyhood dream engendered by a ruby lounger on the pool in TV’s ‘neighbours neighbours’ and sleek silver aluminium tins of coke ‘stocked by Ben’s mum in her fridge’, when walking back from school he and his friend’s shared headphones are yanked off by another boy who tells them ‘some nutter nuked America/while we were still in period 6’. “New York Morning, Six Years On” takes a wry look at the metropolis ‘that turns routine commutes into a high/stakes hockey match’, where MoMA spits him out, hyperventilating, overdosed on postmodernism on Fifth,

The collection’s closing pastoral, “Pink Cones”, brings us back full circle… ‘The door will open on a different garden,/air more intimate and careful in its reach’.

A surefooted homecoming.