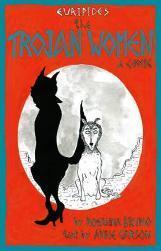

EURIPIDES: THE TROJAN WOMEN, A COMIC: Merryn Williams considers an unusual re-working of Euripides by Anne Carson & Rosanna Bruno

Euripides: The Trojan Women, A Comic

Anne Carson (text) & Rosanna Bruno (pictures)

Bloodaxe Books

ISBN 9781780375908

80pp £10.99

Euripides: The Trojan Women, A Comic

Anne Carson (text) & Rosanna Bruno (pictures)

Bloodaxe Books

ISBN 9781780375908

80pp £10.99

Euripides’ great play, performed and translated countless times, was first acted in Athens in 415 BC. The audience, although they knew the tale of Troy by heart, would immediately have been reminded of the attack by their own government on the little island of Milos the previous year. The adult men had all been killed and the women and children enslaved. ‘The strong do what they can’, the Athenians said in Thucydides’ version, ‘and the weak suffer what they must’.

Most of the characters are captive women. Whether you are an aged former queen, a mother or a virgin priestess, you will inevitably be taken from your homeland to be servants or sex slaves (there is an agonising discussion about whether a woman should try to ingratiate herself with her husband’s killer). Even a child may be murdered because a famous warrior’s son can’t be allowed to grow up. Are the same things happening in various parts of the world today? Yes, of course.

Graphic novels are not to be confused with the old Classics Illustrated. They are aimed at adults and heavily laced with irony; ‘both wacky and devastating’ is how Anne Carson’s version is described in the blurb. Sometimes it’s too wacky for my taste; for instance, on page 6 we’re told ‘you know that poem of Frederick Seidel where James Baldwin is a leopard’ – why should she assume we know it? Then, Hekabe spends much of the play lying on the ground as a gesture of utter defeat. ‘Let me lie where I have fallen’, she says in my translation, but this translator adds the words ‘good posture’s kind of a right-wing concept’. I think it’s too clever by half.

On the plus side, this comic sticks very closely to the story, and the illustrations by Rosanna Bruno add a whole new dimension. The first page depicts a giant wave – ‘Enter Poseidon, a large volume of water measuring 600 clear cubic feet’. That is more effective than an actor dressed up as the king of the sea. A tsunami has already overwhelmed the Trojans, but the Greeks, too, can expect horrible tragedies when they sail home with their slaves. Another whole page features the word NO, repeated innumerable times in white on black.

According to legend, the former queen Hekabe was turned into a dog and left to die in the ruins of Troy. Throughout, she is represented as a dog, and all the other characters, except one, are drawn as non-human. The Herald is a raven, Andromache is a tree, Helen is a glamorous silver fox wearing stilettos, or alternatively a mirror in which each man sees what he desires. The chorus of Trojan women are cows and dogs, people reduced to animals without rights. Menelaos is ‘some sort of gearbox’, accompanied by ‘a herd of cats’.

What kind of sense does all this make? Euripides’ audience knew that Odysseus was going to be shipwrecked, Agamemnon murdered. The prophetess Kassandra, a central figure in Western culture and the only character depicted as a human being, is ecstatic because she knows that some of their enemies are doomed (although she will die too). But there is no abstract justice. Hekabe calls on Zeus ‘to bring all human action back to right at last’ in the scene where she asks for Helen, the cause of the war, to be condemned to death. Menelaos comments, ‘How strange a way to call on gods’ – in this version, ‘What’s this? Some new- age spirituality?’ But, although he author doesn’t say so, his audience knew that Helen, the ultimate trophy woman, would be just fine. The gods have no moral compass.

I liked this comic and hopefully it will introduce a new audience to a timeless play.

Jul 5 2021

EURIPIDES: THE TROJAN WOMEN, A COMIC

EURIPIDES: THE TROJAN WOMEN, A COMIC: Merryn Williams considers an unusual re-working of Euripides by Anne Carson & Rosanna Bruno

Euripides’ great play, performed and translated countless times, was first acted in Athens in 415 BC. The audience, although they knew the tale of Troy by heart, would immediately have been reminded of the attack by their own government on the little island of Milos the previous year. The adult men had all been killed and the women and children enslaved. ‘The strong do what they can’, the Athenians said in Thucydides’ version, ‘and the weak suffer what they must’.

Most of the characters are captive women. Whether you are an aged former queen, a mother or a virgin priestess, you will inevitably be taken from your homeland to be servants or sex slaves (there is an agonising discussion about whether a woman should try to ingratiate herself with her husband’s killer). Even a child may be murdered because a famous warrior’s son can’t be allowed to grow up. Are the same things happening in various parts of the world today? Yes, of course.

Graphic novels are not to be confused with the old Classics Illustrated. They are aimed at adults and heavily laced with irony; ‘both wacky and devastating’ is how Anne Carson’s version is described in the blurb. Sometimes it’s too wacky for my taste; for instance, on page 6 we’re told ‘you know that poem of Frederick Seidel where James Baldwin is a leopard’ – why should she assume we know it? Then, Hekabe spends much of the play lying on the ground as a gesture of utter defeat. ‘Let me lie where I have fallen’, she says in my translation, but this translator adds the words ‘good posture’s kind of a right-wing concept’. I think it’s too clever by half.

On the plus side, this comic sticks very closely to the story, and the illustrations by Rosanna Bruno add a whole new dimension. The first page depicts a giant wave – ‘Enter Poseidon, a large volume of water measuring 600 clear cubic feet’. That is more effective than an actor dressed up as the king of the sea. A tsunami has already overwhelmed the Trojans, but the Greeks, too, can expect horrible tragedies when they sail home with their slaves. Another whole page features the word NO, repeated innumerable times in white on black.

According to legend, the former queen Hekabe was turned into a dog and left to die in the ruins of Troy. Throughout, she is represented as a dog, and all the other characters, except one, are drawn as non-human. The Herald is a raven, Andromache is a tree, Helen is a glamorous silver fox wearing stilettos, or alternatively a mirror in which each man sees what he desires. The chorus of Trojan women are cows and dogs, people reduced to animals without rights. Menelaos is ‘some sort of gearbox’, accompanied by ‘a herd of cats’.

What kind of sense does all this make? Euripides’ audience knew that Odysseus was going to be shipwrecked, Agamemnon murdered. The prophetess Kassandra, a central figure in Western culture and the only character depicted as a human being, is ecstatic because she knows that some of their enemies are doomed (although she will die too). But there is no abstract justice. Hekabe calls on Zeus ‘to bring all human action back to right at last’ in the scene where she asks for Helen, the cause of the war, to be condemned to death. Menelaos comments, ‘How strange a way to call on gods’ – in this version, ‘What’s this? Some new- age spirituality?’ But, although he author doesn’t say so, his audience knew that Helen, the ultimate trophy woman, would be just fine. The gods have no moral compass.

I liked this comic and hopefully it will introduce a new audience to a timeless play.