Poetry review – A SQUARE OF SUNLIGHT: Pat Edwards finds a refreshing acceptance of life’s ups and downs in Meg Cox’s poems

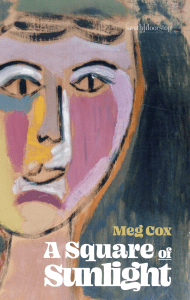

A Square of Sunlight

Meg Cox

Smith Doorstop 2021

ISBN 978-1-912196-85-2

£9.95

A Square of Sunlight

Meg Cox

Smith Doorstop 2021

ISBN 978-1-912196-85-2

£9.95

From the very first poem, the title poem for the collection, the reader knows they are in for something out of the ordinary. A school girl comes home to find,

…her dad

in his cricket whites, prone and beating his fist

on the quarry tiled floor in a square of sunlight.

This image, sad, intriguing, concerning, compelling, is quickly followed by other poems driven by memories of growing up and coming of age. They paint a picture of ordinary things, familiar experiences, seen through the lens of someone with a flair for naughtiness and for noticing absurdity. That proximity of dark and light is always present. Maybe Cox voices the things we would all like to say but dare not. She is unflinching in her recollection of formative events and relationships as in ‘Very Small Italians’ where she tells us,

The first time I had sex in a car

it was in a Fiat 600 and I’m not short.

It’s perhaps what is left unsaid that has as much impact as the secrets she reveals, showing her wicked sense of humour and brilliant comic timing. However, as with all good comedy, there is often pathos. In the modern sonnet, ‘The Third Person in the Marriage’, a title that echoes the infamous Princess Diana comment to Martin Bashir, Cox excels. Amidst the laugh out loud humour, the reader senses loss, anger, deep hurt in:

You said we were finished. But that can’t be true –

it can’t be too late for us – I really love you.

And what has she got, that woman, I’ve not?

Just his kids, a house, my lover. The lot.

The woman wronged is a recurring theme, one handled from many perspectives. Poems happily take the piss out of men who can’t help themselves, who want it all, but also point out the loneliness of the woman who ends up not being the chosen one. Cox draws attention to the absurdity of this kind of love in ‘Cadeau’, French for ‘gift’. Here she borrows from visual artist Man Ray when she talks about ironing her absent lover’s “best shirts”, and suggests her iron is “studded with spikes” like Ray’s iron with nails.

Cox’s poems also display a love of the arts and a cultural awareness, as many of them reference trips abroad and visits to galleries. This adds a depth and gives the work an undercurrent of seriousness. We feel the writer’s grasp of the aesthetic and know she appreciates good art. It’s hard to tell if Cox really sees beauty in the “‘wild mushroom and baby spinach pastry case/with poached duck egg’ which was perfect”, in ‘Recollection in Herefordshire’, or whether this is a sideswipe at modern art. It could be either because Cox is forever juxtaposing lovely things alongside the ridiculous. This unnerving characteristic of her writing is thrilling actually and keeps us thinking long after we have read each poem. An example is ‘Nightingales’, where the poet plays with who said what to whom about real or imagined birdsong; the point being that “perhaps tonight I will hear the nightingales/and your voice. In my dreams.”

The poet’s brother features in some of the poems, clearly a beloved sibling, and one to whom she “would like to have thought/of something I could have said…before it was too late.” This sense of loss is another constant theme. Poems talk of fading youth, of soldiers lost to war, of missed opportunities, even diminishing hope. One metaphor that carries some of this is the bird. In ‘Bird of Prey’ the poet almost screeches at us, “This Bird is dangerous./Given half a bloody chance.” The poet recognises and celebrates the freedom of swifts in ‘Never Mind D H Lawrence’, where she rejoices, “swifts, they’re the boys.” The final poem in the book is ‘Landing’. This poem charts the way water fowl land on water but feels much more like the poet’s description of how we all strive to “glide away, swanlike”.

No reviewer – indeed no writer – could leave this collection without celebrating the effortlessly wonderful poem ‘My Friend the Prize-Winning Poet’. In this Cox does again what I gave her credit for earlier, proclaiming what most of us are afraid to say out loud:

Of course I smiled and smiled

and said I loved one particular line

in her winning poem – the last is a pretty safe bet

but I hadn’t actually read it

and I won’t be fucking reading it either.

Although this collection often looks back it is never sentimental or clouded by a false rosy glow. Cox is fundamentally honest and pragmatic; we feel her wisdom in accepting what has been, in fact, of acknowledging her role in how things played out. The poet never seeks sympathy but invites us to laugh, consider, weigh up and move on. Whatever else there is in a life lived fast and furious, we may all be grateful for “a square of sunlight” and “the juice of a glut of ripe strawberries”.

Jun 14 2021

London Grip Poetry Review – Meg Cox

Poetry review – A SQUARE OF SUNLIGHT: Pat Edwards finds a refreshing acceptance of life’s ups and downs in Meg Cox’s poems

From the very first poem, the title poem for the collection, the reader knows they are in for something out of the ordinary. A school girl comes home to find,

This image, sad, intriguing, concerning, compelling, is quickly followed by other poems driven by memories of growing up and coming of age. They paint a picture of ordinary things, familiar experiences, seen through the lens of someone with a flair for naughtiness and for noticing absurdity. That proximity of dark and light is always present. Maybe Cox voices the things we would all like to say but dare not. She is unflinching in her recollection of formative events and relationships as in ‘Very Small Italians’ where she tells us,

It’s perhaps what is left unsaid that has as much impact as the secrets she reveals, showing her wicked sense of humour and brilliant comic timing. However, as with all good comedy, there is often pathos. In the modern sonnet, ‘The Third Person in the Marriage’, a title that echoes the infamous Princess Diana comment to Martin Bashir, Cox excels. Amidst the laugh out loud humour, the reader senses loss, anger, deep hurt in:

The woman wronged is a recurring theme, one handled from many perspectives. Poems happily take the piss out of men who can’t help themselves, who want it all, but also point out the loneliness of the woman who ends up not being the chosen one. Cox draws attention to the absurdity of this kind of love in ‘Cadeau’, French for ‘gift’. Here she borrows from visual artist Man Ray when she talks about ironing her absent lover’s “best shirts”, and suggests her iron is “studded with spikes” like Ray’s iron with nails.

Cox’s poems also display a love of the arts and a cultural awareness, as many of them reference trips abroad and visits to galleries. This adds a depth and gives the work an undercurrent of seriousness. We feel the writer’s grasp of the aesthetic and know she appreciates good art. It’s hard to tell if Cox really sees beauty in the “‘wild mushroom and baby spinach pastry case/with poached duck egg’ which was perfect”, in ‘Recollection in Herefordshire’, or whether this is a sideswipe at modern art. It could be either because Cox is forever juxtaposing lovely things alongside the ridiculous. This unnerving characteristic of her writing is thrilling actually and keeps us thinking long after we have read each poem. An example is ‘Nightingales’, where the poet plays with who said what to whom about real or imagined birdsong; the point being that “perhaps tonight I will hear the nightingales/and your voice. In my dreams.”

The poet’s brother features in some of the poems, clearly a beloved sibling, and one to whom she “would like to have thought/of something I could have said…before it was too late.” This sense of loss is another constant theme. Poems talk of fading youth, of soldiers lost to war, of missed opportunities, even diminishing hope. One metaphor that carries some of this is the bird. In ‘Bird of Prey’ the poet almost screeches at us, “This Bird is dangerous./Given half a bloody chance.” The poet recognises and celebrates the freedom of swifts in ‘Never Mind D H Lawrence’, where she rejoices, “swifts, they’re the boys.” The final poem in the book is ‘Landing’. This poem charts the way water fowl land on water but feels much more like the poet’s description of how we all strive to “glide away, swanlike”.

No reviewer – indeed no writer – could leave this collection without celebrating the effortlessly wonderful poem ‘My Friend the Prize-Winning Poet’. In this Cox does again what I gave her credit for earlier, proclaiming what most of us are afraid to say out loud:

Although this collection often looks back it is never sentimental or clouded by a false rosy glow. Cox is fundamentally honest and pragmatic; we feel her wisdom in accepting what has been, in fact, of acknowledging her role in how things played out. The poet never seeks sympathy but invites us to laugh, consider, weigh up and move on. Whatever else there is in a life lived fast and furious, we may all be grateful for “a square of sunlight” and “the juice of a glut of ripe strawberries”.