PAUL McLOUGHLIN 1947-2021: John Lucas recalls his friendship with the late Paul McLoughlin and reprises some of the poetry and music they shared

.

.

The following words are not meant to provide an obituary of my friend. I wrote a bare-bones account of Paul’s life for PN Review, and another has already appeared on London Grip. I have no doubt that these will be supplemented by further, more detailed obituaries, written by one or other of the many friends who knew him from his early days. Those early days included his rebellious period at Gunnersbury Catholic Grammar School, which he loathed, and which he left after his sixteenth birthday with two O Levels to his name. After that he found employment as a clerical assistant at Sun Life Insurance, which I can’t imagine he much enjoyed. At all events he soon became a part-time student at various London Institutes of Education – supporting himself by casual jobs; then, after securing two A Levels followed by part-time degree work at Chiswick Poly, he became a qualified a school-teacher. He began a teaching career, married, graduated to fatherhood, was soon earning his spurs as a jazz flautist and alto saxophonist, then – or was it coincidentally? – realised that he was a poet, and, as we all do, began to send out his poems to serious magazines and journals. By the 1990s was ready to publish his first collection – in his case with Smith/Doorstop.

So by the time he and I met, early in the new millennium, I think I’m right in saying that he had retired from teaching and was free to concentrate on poetry and jazz. He had already published a pamphlet with Smith/Doorstop, and I had accepted for publication another slim collection What Moves Moves and was looking forward to meeting its author in Newcastle, where it was to be launched together with another collection by the poet and artist, Peter Bennet.

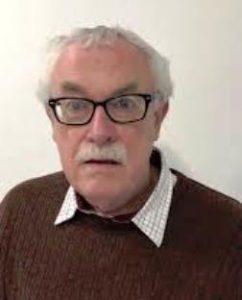

The man who introduced himself to me on that occasion shook hands warmly but with no trace of effusiveness, and his smile, one of rueful candour, was accompanied with a slight slump of his shoulders, as if to suggest that he knew there was more to life than all this mullarkey. But his cheese-grater voice came as a shock. Louis Armstrong on speed, perhaps? (Later, I learnt it was the result of an operation for throat cancer.) Still, it didn’t impede his very effective reading manner. There was a goodly crowd packed into the upper room of the central Newcastle pub that hosted the event, and after his and Peter’s well-received readings ended there was much convivial talk before I left to take a train for Durham, where I was due to stay with my close friend, Anne Stevenson. Paul had been offered and had accepted a bed at Peter’s house, which I seem to remember being told was on top of a hill outside the city.

The man who introduced himself to me on that occasion shook hands warmly but with no trace of effusiveness, and his smile, one of rueful candour, was accompanied with a slight slump of his shoulders, as if to suggest that he knew there was more to life than all this mullarkey. But his cheese-grater voice came as a shock. Louis Armstrong on speed, perhaps? (Later, I learnt it was the result of an operation for throat cancer.) Still, it didn’t impede his very effective reading manner. There was a goodly crowd packed into the upper room of the central Newcastle pub that hosted the event, and after his and Peter’s well-received readings ended there was much convivial talk before I left to take a train for Durham, where I was due to stay with my close friend, Anne Stevenson. Paul had been offered and had accepted a bed at Peter’s house, which I seem to remember being told was on top of a hill outside the city.

I saw Paul next in London, a week later, this time at Bookmarks, the excellent socialist bookshop near the British Museum which over the years was to become Shoestring’s regular London launching pad and where What Moves Moves was to have its London baptism. How he and his host had got on, I wanted to know. Paul adopted his slump-shouldered stance. ‘Alright,’ he said, ‘he was good company.’ A pause. ‘But blimey, he can’t half talk. We didn’t get to bed until 4 a.m.’

Not then knowing Paul as well I came to do in later years, I assumed that long before the evening ended he had begun to yearn for his bed. But deepening acquaintance brought new levels of understanding, and with growing friendship a realisation that when it came to talk Paul was in a class of his own. He came from a large Irish family, and ‘Craik,’ or ‘crack’, is I think the word his fellow-countrymen use for good and lively talk. Dr Johnson, that adopted Londoner, put it differently. ‘Let us fold our knees and have out our chat’ he commanded friends he met in coffee-house or tavern. For Johnson, while no Irishman, dearly loved talk, especially talk between friends, and especially what he called ‘tavern talk.’

Paul’s way of opening talk, craik, chat – call it what you will – was to come to a halt directly in front of you, fix you with a glittering if quizzical eye, open his mouth, and begin. A favourite opener was, ‘Have you heard?’, the last word uttered on a rising note and with a kind of half comic, outraged emphasis, after which he would set you right about some unpleasant governmental pronouncement or the benighted critical denunciation of a favourite poet or a recent back page dismissal of Brentford FC ’s chances of promotion to football’s premier league, or … or….Paul didn’t need a pub, though, to adapt Byron, he had no objection to a pint of beer; what he did require was to find himself in the company of someone – anyone – who shared one or more of his interests. And given that these were as many and various as his friends were numerous, the opportunity for talk was seldom lacking.

It was good talk: witty, always informed, and, except when it came to Brentford, plausible. Readers of London Grip, among other journals, will know how good a poetry reviewer Paul was, perceptive, judicious, wide-ranging in his sympathies. And his excellent New & Selected Poems of Brian Jones, which I was delighted to publish and which came out of his Doctoral thesis (examined by the distinguished poet-critic Grevel Lindop and myself) has a lengthy Introduction that seems to me a model of its kind. Informed, deftly written, and as illuminating as it is well-balanced. It couldn’t, I am certain, have been written by anyone who was not himself a good poet. Helen Dumore’s praise of Paul’s own verse – it possessed, she said, ‘a rare clarity and exactitude’ – is spot on. His talk was like that, though it also contained rare gobbets of out-of-the-way information or speculative wit. I can’t believe that anyone meeting Paul for the first time wouldn’t be eager for the second chance.

And then there is his music. As is often the way with jazz musicians, Paul was initially self-taught (though he was a good reader of ‘the dots’ as many aren’t). He later studied music at an academic level and eventually gained mastery over the flute before moving on to play both it and alto-sax with a semi-professional quartet which included his brother, Mick. They had regular gigs in the London area, including the riotous occasion when, at the end of 2004, I launched the Shoestring anthology, Paging Doctor Jazz. The party for this was held in the upper room of a North London pub, with musical contributions from, among others, John Mole (clarinet), plus an excellent pianist nephew of mine (piano and vocal), with Paul’s quartet acting as house band for the evening. The room, large though it was, contained at least double the permitted number of attendees, evenly divided between poets and jazz aficionados, the latter of whom had sniffed out the chance of some free beer, and a few of whom actually paid nominal sums for the books they all pocketed.

And then there is his music. As is often the way with jazz musicians, Paul was initially self-taught (though he was a good reader of ‘the dots’ as many aren’t). He later studied music at an academic level and eventually gained mastery over the flute before moving on to play both it and alto-sax with a semi-professional quartet which included his brother, Mick. They had regular gigs in the London area, including the riotous occasion when, at the end of 2004, I launched the Shoestring anthology, Paging Doctor Jazz. The party for this was held in the upper room of a North London pub, with musical contributions from, among others, John Mole (clarinet), plus an excellent pianist nephew of mine (piano and vocal), with Paul’s quartet acting as house band for the evening. The room, large though it was, contained at least double the permitted number of attendees, evenly divided between poets and jazz aficionados, the latter of whom had sniffed out the chance of some free beer, and a few of whom actually paid nominal sums for the books they all pocketed.

A few years later Paul drove himself and John Hartley Williams to Nottingham for my seventieth birthday (garden) party, held to coincide with that year’s Lowdham Summer Festival, and though John, who was no mean pianist, declined the chance to demonstrate his prowess at the keyboard, Paul sat in with my own group, The Burgundy Street Jazzmen, this time bringing his clarinet. (Our style was New Orleans to Mainstream.) We chose to play an old standard, ‘Indiana’ – ‘In the key of F’ I said, but Paul knew. ‘He’s alright, he is,’ Lol our drummer said afterward, which commendation, coming from Lol, was praise indeed. But it was true.

In Paul’s more recent years, I rather think that the chances to play jazz dropped away; but left more time for him to practise the art of poetry, and his work got steadily better and better, so that the most recent collection, The Hungarian Who Beat Brazil (2017), is, I think, a work of rare accomplishment. The title poem in particular, a mini-narrative, is handled without undue emphasis but with an enviably deft control; and the movement across the line-endings is quite masterly. During these years he began to send Christmas Cards to friends with, pasted into them, a poem written at, though not necessarily for, the season, and I imagine all the recipients came to treasure each year’s card. It was, you could say, an ideal token of friendship.

At some time in the early to mid-teens I was able to introduce Paul to the Australian poet, Andrew Sant, whom I’d met in Tasmania some years earlier, and who for a number of years came regularly to take up teaching posts in England, courtesy of the Royal Literary Fund, and the two of them got on as well as I’d predicted they would. They were roughly the same age, and Andrew, who was taken to Australia when he was ten, had been born in Essex. More importantly, they both enjoyed good crack, and were appreciative of the work of Les Murray, not a poet to everyone’s taste, though Paul has a lovely, witty, sympathetic poem about an occasion when Murray, on one of his frequent visits to England, stayed chez McLoughlin.

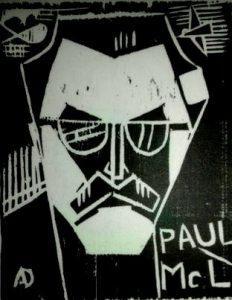

By that time, Pauline and I were spending part of each summer in a small rented flat on the Greek visland of Aegina, which Andrew and his partner, Tina, sometimes visited as part of their European rambles. On two of these occasions Paul, too, came to the island, once with his wife Nina, once on his own. There was a nearby taverna on the harbour front of the village, Faros, where our flat was, and we’d sit out under the stars, drinking retsina and talking, talking, talking, the wittily laconic Andrew, the volubly witty Paul: Yin and Yang, while the rest of us joined in or found other matters to discuss. And among those absent friends to whom we drank was always that excellent poet and woodcut artist, Alan Dixon, Alan who rarely left his house in Eastbourne, though a delightful host and welcoming to those who admired his work. I’d known it for several years, had published his poetry, and at different times Andrew and Paul both made the pilgrimage to Eastbourne, where Alan produced superb woodcut images of them both. As a result a considerable bond was established between the four of us, perhaps best epitomised in the book of Alan’s woodcuts with accompanying poems by various poets which I published under the title Wood & Ink. It’s a book of which I’m intensely proud, containing as it does excellent contributions by both Paul and Andrew, and the book was wonderfully well seen through to publication by my typesetters, then known as Narrator, now as The Book Typesetters, and to me, always, as simply the best in the land.

Now, with Paul’s unlooked-for death, that bond is badly frayed, though it’s good to be able to report that The Hungarian Who Beat Brazil has on its back cover a particularly fine, witty woodcut image of Paul’s head by Alan. If you haven’t yet bought a copy of the collection, do so! And as for you, Paul, good poet and dear friend, there are no words to express my grateful thanks for having known you.

Apr 28 2021

PAUL McLOUGHLIN, POET AND JAZZ MUSICIAN, 1947 – 2021

PAUL McLOUGHLIN 1947-2021: John Lucas recalls his friendship with the late Paul McLoughlin and reprises some of the poetry and music they shared

The following words are not meant to provide an obituary of my friend. I wrote a bare-bones account of Paul’s life for PN Review, and another has already appeared on London Grip. I have no doubt that these will be supplemented by further, more detailed obituaries, written by one or other of the many friends who knew him from his early days. Those early days included his rebellious period at Gunnersbury Catholic Grammar School, which he loathed, and which he left after his sixteenth birthday with two O Levels to his name. After that he found employment as a clerical assistant at Sun Life Insurance, which I can’t imagine he much enjoyed. At all events he soon became a part-time student at various London Institutes of Education – supporting himself by casual jobs; then, after securing two A Levels followed by part-time degree work at Chiswick Poly, he became a qualified a school-teacher. He began a teaching career, married, graduated to fatherhood, was soon earning his spurs as a jazz flautist and alto saxophonist, then – or was it coincidentally? – realised that he was a poet, and, as we all do, began to send out his poems to serious magazines and journals. By the 1990s was ready to publish his first collection – in his case with Smith/Doorstop.

So by the time he and I met, early in the new millennium, I think I’m right in saying that he had retired from teaching and was free to concentrate on poetry and jazz. He had already published a pamphlet with Smith/Doorstop, and I had accepted for publication another slim collection What Moves Moves and was looking forward to meeting its author in Newcastle, where it was to be launched together with another collection by the poet and artist, Peter Bennet.

I saw Paul next in London, a week later, this time at Bookmarks, the excellent socialist bookshop near the British Museum which over the years was to become Shoestring’s regular London launching pad and where What Moves Moves was to have its London baptism. How he and his host had got on, I wanted to know. Paul adopted his slump-shouldered stance. ‘Alright,’ he said, ‘he was good company.’ A pause. ‘But blimey, he can’t half talk. We didn’t get to bed until 4 a.m.’

Not then knowing Paul as well I came to do in later years, I assumed that long before the evening ended he had begun to yearn for his bed. But deepening acquaintance brought new levels of understanding, and with growing friendship a realisation that when it came to talk Paul was in a class of his own. He came from a large Irish family, and ‘Craik,’ or ‘crack’, is I think the word his fellow-countrymen use for good and lively talk. Dr Johnson, that adopted Londoner, put it differently. ‘Let us fold our knees and have out our chat’ he commanded friends he met in coffee-house or tavern. For Johnson, while no Irishman, dearly loved talk, especially talk between friends, and especially what he called ‘tavern talk.’

Paul’s way of opening talk, craik, chat – call it what you will – was to come to a halt directly in front of you, fix you with a glittering if quizzical eye, open his mouth, and begin. A favourite opener was, ‘Have you heard?’, the last word uttered on a rising note and with a kind of half comic, outraged emphasis, after which he would set you right about some unpleasant governmental pronouncement or the benighted critical denunciation of a favourite poet or a recent back page dismissal of Brentford FC ’s chances of promotion to football’s premier league, or … or….Paul didn’t need a pub, though, to adapt Byron, he had no objection to a pint of beer; what he did require was to find himself in the company of someone – anyone – who shared one or more of his interests. And given that these were as many and various as his friends were numerous, the opportunity for talk was seldom lacking.

It was good talk: witty, always informed, and, except when it came to Brentford, plausible. Readers of London Grip, among other journals, will know how good a poetry reviewer Paul was, perceptive, judicious, wide-ranging in his sympathies. And his excellent New & Selected Poems of Brian Jones, which I was delighted to publish and which came out of his Doctoral thesis (examined by the distinguished poet-critic Grevel Lindop and myself) has a lengthy Introduction that seems to me a model of its kind. Informed, deftly written, and as illuminating as it is well-balanced. It couldn’t, I am certain, have been written by anyone who was not himself a good poet. Helen Dumore’s praise of Paul’s own verse – it possessed, she said, ‘a rare clarity and exactitude’ – is spot on. His talk was like that, though it also contained rare gobbets of out-of-the-way information or speculative wit. I can’t believe that anyone meeting Paul for the first time wouldn’t be eager for the second chance.

A few years later Paul drove himself and John Hartley Williams to Nottingham for my seventieth birthday (garden) party, held to coincide with that year’s Lowdham Summer Festival, and though John, who was no mean pianist, declined the chance to demonstrate his prowess at the keyboard, Paul sat in with my own group, The Burgundy Street Jazzmen, this time bringing his clarinet. (Our style was New Orleans to Mainstream.) We chose to play an old standard, ‘Indiana’ – ‘In the key of F’ I said, but Paul knew. ‘He’s alright, he is,’ Lol our drummer said afterward, which commendation, coming from Lol, was praise indeed. But it was true.

In Paul’s more recent years, I rather think that the chances to play jazz dropped away; but left more time for him to practise the art of poetry, and his work got steadily better and better, so that the most recent collection, The Hungarian Who Beat Brazil (2017), is, I think, a work of rare accomplishment. The title poem in particular, a mini-narrative, is handled without undue emphasis but with an enviably deft control; and the movement across the line-endings is quite masterly. During these years he began to send Christmas Cards to friends with, pasted into them, a poem written at, though not necessarily for, the season, and I imagine all the recipients came to treasure each year’s card. It was, you could say, an ideal token of friendship.

At some time in the early to mid-teens I was able to introduce Paul to the Australian poet, Andrew Sant, whom I’d met in Tasmania some years earlier, and who for a number of years came regularly to take up teaching posts in England, courtesy of the Royal Literary Fund, and the two of them got on as well as I’d predicted they would. They were roughly the same age, and Andrew, who was taken to Australia when he was ten, had been born in Essex. More importantly, they both enjoyed good crack, and were appreciative of the work of Les Murray, not a poet to everyone’s taste, though Paul has a lovely, witty, sympathetic poem about an occasion when Murray, on one of his frequent visits to England, stayed chez McLoughlin.

By that time, Pauline and I were spending part of each summer in a small rented flat on the Greek visland of Aegina, which Andrew and his partner, Tina, sometimes visited as part of their European rambles. On two of these occasions Paul, too, came to the island, once with his wife Nina, once on his own. There was a nearby taverna on the harbour front of the village, Faros, where our flat was, and we’d sit out under the stars, drinking retsina and talking, talking, talking, the wittily laconic Andrew, the volubly witty Paul: Yin and Yang, while the rest of us joined in or found other matters to discuss. And among those absent friends to whom we drank was always that excellent poet and woodcut artist, Alan Dixon, Alan who rarely left his house in Eastbourne, though a delightful host and welcoming to those who admired his work. I’d known it for several years, had published his poetry, and at different times Andrew and Paul both made the pilgrimage to Eastbourne, where Alan produced superb woodcut images of them both. As a result a considerable bond was established between the four of us, perhaps best epitomised in the book of Alan’s woodcuts with accompanying poems by various poets which I published under the title Wood & Ink. It’s a book of which I’m intensely proud, containing as it does excellent contributions by both Paul and Andrew, and the book was wonderfully well seen through to publication by my typesetters, then known as Narrator, now as The Book Typesetters, and to me, always, as simply the best in the land.

Now, with Paul’s unlooked-for death, that bond is badly frayed, though it’s good to be able to report that The Hungarian Who Beat Brazil has on its back cover a particularly fine, witty woodcut image of Paul’s head by Alan. If you haven’t yet bought a copy of the collection, do so! And as for you, Paul, good poet and dear friend, there are no words to express my grateful thanks for having known you.