Poetry review – BREAKFAST AT THE ORIGAMI CAFÉ: Carla Scarano D’Antonio is gripped by a powerful story that runs through Tess Jolly’s new collection

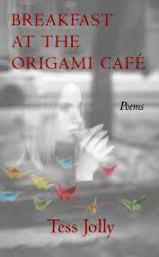

Breakfast at the Origami Café

Tess Jolly

Blue Diode Press

ISBN 978191645141

£10

Breakfast at the Origami Café

Tess Jolly

Blue Diode Press

ISBN 978191645141

£10

Tess Jolly’s first full collection tells its story in a powerful and emotional way about a family whose atmosphere is permeated by trauma and violence. A manipulating mother figure threatens the narrator’s self-esteem both physically and psychologically. Nevertheless, she slowly recovers, revisiting her memories, finding new ways to connect and, above all, creating new relationships with her partner, her children and her friends. The wounds are stitched together little by little and she can make space for a more hopeful future.

The collection is divided into four sections that trace the poet’s journey from the traumatic memories of her childhood and her teenage years to a recovery that allows her to savour life again:

Now I’m the age you were then,

have a daughter of my own

to protect, hold close, I know

why you pinned me down

on the carpet that night, pressed

your knees to my shoulders

to keep me from going out again.

(‘Pact’)

The first section describes the effects of the shocking experience. Although accepting and understanding it eventually, the narrator cannot help feeling a ‘disgust’ that had consequences throughout her life, causing her to self-harm and making her feel ‘smaller and smaller’. These incidents are beautifully and insightfully revisited in the title poem, ‘Breakfast at the Origami Café’, in which the practice of folding origami shapes is metaphorically used to show the manipulative and sometimes abusive quality of relationships:

A mother tenderly folds her daughter

at the waist, demonstrates making a swan.

Her husband invites her to crease

the dotted lines of his spine, butterfly-paint

one tattooed side of his back to the other.

Relations can be complex and demanding so there is a need to surrender sometimes, or, on other occasions, be assertive, swapping the roles of victim and victimiser. These roles seem to be tightly connected, shaping one another in forms that are forced on the individual and are marked by scars that ‘speckle the exterior’. The origami shapes are fascinating and decorative objects but maybe they can be unfolded in time and reconstructed in a different, looser way.

In the next three sections, Jolly’s poetry develops in thoughtful and evocative ways and impressive imageries. A deep sense of place and time, the northern landscape and new family relationships mingle and renew her language so that it displays musical alliterations and a skilful use of repetitions:

Not the flame, its tongue

that licked my mother into shape,

but this pit of char and ash,

these final glowing embers.

Not the walls he built brick by brick

into a temple of threat,

but this forgotten heap of ruins

the strangler figs have claimed.

[…]

Not the brute in the doorway,

his laughing, dancing fists,

but this bag of skin the wind

has blown across his bones.

(‘Not the Flame’)

Cradled by the bones of me, born of my breath,

forged from the brimstone, the butter, the bread,

in ballads we’ve sung, their brambles, their beauty,

from banquets we feast on, such everyday bounty,

in blossom that garland, the bedlam I fear,

from the butcher I am, the bullets that pierce

(‘Bairn’)

The poems convey a sense of loss that seems inevitable and whose meaning is regained through poetic language in a creative process that reshapes and heals the self – or at least allows possible escapes from the entrapping past. This recovery is consuming and goes through temporary self-annihilation, reducing the protagonist to the essential, to the bones, that are eventually rebuilt in unexpected ways and unusual forms through language. Not everything can be explained and understood in full, but ‘this bridge, this bond’ can be put together again in a renewal of sorts. Hope is presented in light and shadow that alternate and coexist, as in ‘St Ives’, the last poem of the collection. Here the ‘tent is pitched/amongst the rocks and the heather’ but the streets are dark as the poet weighs her shadow and past memories still loom.

Frustration, unanswered questions and an uncertain future persist throughout; but nevertheless, the future is open to further explorations. These explorations may involve failures and moments of darkness and disillusionment but there is also a ‘needle of light/and gulls […]/lacing your thoughts with their cries’. And there is love as well.

The recurrent metaphor of the ‘piles of bones’ is what is left from the traumas at the start of the book; it does not seem much but it is the core that can be relied on – it is strong and vulnerable at the same time. It is resilient and represents the narrator’s wish to reshape her self.

Apr 14 2021

London Grip Poetry Review – Tess Jolly

Poetry review – BREAKFAST AT THE ORIGAMI CAFÉ: Carla Scarano D’Antonio is gripped by a powerful story that runs through Tess Jolly’s new collection

Tess Jolly’s first full collection tells its story in a powerful and emotional way about a family whose atmosphere is permeated by trauma and violence. A manipulating mother figure threatens the narrator’s self-esteem both physically and psychologically. Nevertheless, she slowly recovers, revisiting her memories, finding new ways to connect and, above all, creating new relationships with her partner, her children and her friends. The wounds are stitched together little by little and she can make space for a more hopeful future.

The collection is divided into four sections that trace the poet’s journey from the traumatic memories of her childhood and her teenage years to a recovery that allows her to savour life again:

Now I’m the age you were then, have a daughter of my own to protect, hold close, I know why you pinned me down on the carpet that night, pressed your knees to my shoulders to keep me from going out again. (‘Pact’)The first section describes the effects of the shocking experience. Although accepting and understanding it eventually, the narrator cannot help feeling a ‘disgust’ that had consequences throughout her life, causing her to self-harm and making her feel ‘smaller and smaller’. These incidents are beautifully and insightfully revisited in the title poem, ‘Breakfast at the Origami Café’, in which the practice of folding origami shapes is metaphorically used to show the manipulative and sometimes abusive quality of relationships:

Relations can be complex and demanding so there is a need to surrender sometimes, or, on other occasions, be assertive, swapping the roles of victim and victimiser. These roles seem to be tightly connected, shaping one another in forms that are forced on the individual and are marked by scars that ‘speckle the exterior’. The origami shapes are fascinating and decorative objects but maybe they can be unfolded in time and reconstructed in a different, looser way.

In the next three sections, Jolly’s poetry develops in thoughtful and evocative ways and impressive imageries. A deep sense of place and time, the northern landscape and new family relationships mingle and renew her language so that it displays musical alliterations and a skilful use of repetitions:

Not the flame, its tongue that licked my mother into shape, but this pit of char and ash, these final glowing embers. Not the walls he built brick by brick into a temple of threat, but this forgotten heap of ruins the strangler figs have claimed. […] Not the brute in the doorway, his laughing, dancing fists, but this bag of skin the wind has blown across his bones. (‘Not the Flame’) Cradled by the bones of me, born of my breath, forged from the brimstone, the butter, the bread, in ballads we’ve sung, their brambles, their beauty, from banquets we feast on, such everyday bounty, in blossom that garland, the bedlam I fear, from the butcher I am, the bullets that pierce (‘Bairn’)The poems convey a sense of loss that seems inevitable and whose meaning is regained through poetic language in a creative process that reshapes and heals the self – or at least allows possible escapes from the entrapping past. This recovery is consuming and goes through temporary self-annihilation, reducing the protagonist to the essential, to the bones, that are eventually rebuilt in unexpected ways and unusual forms through language. Not everything can be explained and understood in full, but ‘this bridge, this bond’ can be put together again in a renewal of sorts. Hope is presented in light and shadow that alternate and coexist, as in ‘St Ives’, the last poem of the collection. Here the ‘tent is pitched/amongst the rocks and the heather’ but the streets are dark as the poet weighs her shadow and past memories still loom.

Frustration, unanswered questions and an uncertain future persist throughout; but nevertheless, the future is open to further explorations. These explorations may involve failures and moments of darkness and disillusionment but there is also a ‘needle of light/and gulls […]/lacing your thoughts with their cries’. And there is love as well.

The recurrent metaphor of the ‘piles of bones’ is what is left from the traumas at the start of the book; it does not seem much but it is the core that can be relied on – it is strong and vulnerable at the same time. It is resilient and represents the narrator’s wish to reshape her self.