Poetry review – THE GOD OF LOST WAYS: Neil Leadbeater admires Jane Lovell’s eye for detail as revealed in her latest collection

The God of Lost Ways

Jane Lovell

Indigo Dreams Publishing

ISBN: 978-1912876419

£9-50

The God of Lost Ways

Jane Lovell

Indigo Dreams Publishing

ISBN: 978-1912876419

£9-50

Jane Lovell is an award-winning poet whose work focuses on our relationship with the planet and its wildlife. She lives in Kent and is Writer-in-Residence at Rye Harbour Nature Reserve. The God of Lost Ways was Joint Winner of the Geoff Stevens Memorial Poetry Prize 2020. Unusually, the book is dedicated to days spent in various places rather than to people, one of these places being the Greensand Way, a long-distance footpath that runs from Haslemere in Surrey to Hamstreet in Kent.

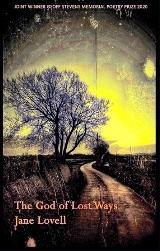

Saffron Swansborough’s Goldleaf: a John Atkinson Grimshaw homage is the perfect cover image for Jane Lovell’s latest collection. The branches of the winter trees illuminated by the golden glow of the sky lays bare the architecture of their forms just as Lovell’s poetry lays bare in almost forensic detail the lives of animals in the natural world.

Those of us who live in towns and cities tend to have a romanticised, artificial view of what it must be like to live in the countryside. In Lovell’s countryside, all is not what it seems: her poems bring us face to face with its harsh realities, its cruelty and its violence. These are dark poems tinged with beauty. The beauty is to be found in Lovell’s powers of observation, description and compassion.

As a keen birdwatcher, many of her poems focus on birds: a blackbird who ‘seduces worms with his rain dance; a dead pheasant ‘tousled / and leaf-bombed by gales / of passing traffic’; a kestrel hunting for mice in a churchyard; starlings and fieldfares, owls, linnets and wrens. This is not all about birds though. There are also poems about hornets, badgers, pigs, dogs, cats and foxes. Most of these animals are casualties. There is a dog with a damaged hip, an owl that has died after having been trapped in a chimney, hornets being gassed, a man with a crippled dog, a dying crow and a dead badger found by the roadside: ‘By evening, someone / with a shovel moves him / slings him off / into the hedge.’ The relentless emphasis on suffering and death makes for grim reading but there are occasions when Lovell’s descriptions soar. She writes fondly of a kestrel (with stylistic echoes of Gerard Manley Hopkins) describing the bird as ‘my beautiful kohl-eyed / tempest angel’ and projects surprising and rewarding images such as one about a peony that is thriving in a neglected garden:

The peony has never looked so good, so vibrant;

her blooms loll like woozy ladies on a lawn

brilliant with lipstick and scandal.

‘Hare’ is Lovell at her best. She describes him as ‘sitting bold as a stray on the lawn’ and then

in a heartbeat, he’s away to the skyline,

unzipping the grass and wind-chased verge

….

all the way to the furthest corner

where he pauses,

resting on his haunches

in the lee of a budding lilac…

Nature refuses to pander to our aesthetic tastes. It follows its own unruly behaviour. In ‘Plum’ Lovell writes about a tree whose trunk has to be supported ‘with a spade and the prop / from the clothes’ line’. We’ve all seen the unwieldy shape of these trees at some point in our lives. ‘You need your trees to be vertical’ she remarks, but the wild plum ‘continues / to grow undeterred, quietly collecting / birdsong in its phloem, / tucking it away in bright sharp notes.’

Not all of these poems worked for me. The last two stanzas of ‘Two men and a hornet’s nest’ seemed to be unrelated to the rest of the poem and thereby weakened its force. The abrupt shift in ‘Margaret’ does not, for me, fit easily with the first three stanzas describing a garden in neglect even though I appreciate that, the way it is titled, ‘Margaret’ is the subject of the poem.

Picking my way through the bones and carcasses of dead animals, I also longed for more variety in the subject matter: less emphasis on the darker side of nature poetry and more on a wider appreciation of the countryside.

In an interview posted in Project on 1 May 2019, (Rye Harbour Discovery Centre), Lovell tells us about her passion for wildlife and, particularly, ornithology and how she likes to collect fossils and found objects. This attention to detail is clearly made manifest in her writing and is one of her many strengths as a writer.

Apr 13 2021

London Grip Poetry Review – Jane Lovell

Poetry review – THE GOD OF LOST WAYS: Neil Leadbeater admires Jane Lovell’s eye for detail as revealed in her latest collection

Jane Lovell is an award-winning poet whose work focuses on our relationship with the planet and its wildlife. She lives in Kent and is Writer-in-Residence at Rye Harbour Nature Reserve. The God of Lost Ways was Joint Winner of the Geoff Stevens Memorial Poetry Prize 2020. Unusually, the book is dedicated to days spent in various places rather than to people, one of these places being the Greensand Way, a long-distance footpath that runs from Haslemere in Surrey to Hamstreet in Kent.

Saffron Swansborough’s Goldleaf: a John Atkinson Grimshaw homage is the perfect cover image for Jane Lovell’s latest collection. The branches of the winter trees illuminated by the golden glow of the sky lays bare the architecture of their forms just as Lovell’s poetry lays bare in almost forensic detail the lives of animals in the natural world.

Those of us who live in towns and cities tend to have a romanticised, artificial view of what it must be like to live in the countryside. In Lovell’s countryside, all is not what it seems: her poems bring us face to face with its harsh realities, its cruelty and its violence. These are dark poems tinged with beauty. The beauty is to be found in Lovell’s powers of observation, description and compassion.

As a keen birdwatcher, many of her poems focus on birds: a blackbird who ‘seduces worms with his rain dance; a dead pheasant ‘tousled / and leaf-bombed by gales / of passing traffic’; a kestrel hunting for mice in a churchyard; starlings and fieldfares, owls, linnets and wrens. This is not all about birds though. There are also poems about hornets, badgers, pigs, dogs, cats and foxes. Most of these animals are casualties. There is a dog with a damaged hip, an owl that has died after having been trapped in a chimney, hornets being gassed, a man with a crippled dog, a dying crow and a dead badger found by the roadside: ‘By evening, someone / with a shovel moves him / slings him off / into the hedge.’ The relentless emphasis on suffering and death makes for grim reading but there are occasions when Lovell’s descriptions soar. She writes fondly of a kestrel (with stylistic echoes of Gerard Manley Hopkins) describing the bird as ‘my beautiful kohl-eyed / tempest angel’ and projects surprising and rewarding images such as one about a peony that is thriving in a neglected garden:

‘Hare’ is Lovell at her best. She describes him as ‘sitting bold as a stray on the lawn’ and then

Nature refuses to pander to our aesthetic tastes. It follows its own unruly behaviour. In ‘Plum’ Lovell writes about a tree whose trunk has to be supported ‘with a spade and the prop / from the clothes’ line’. We’ve all seen the unwieldy shape of these trees at some point in our lives. ‘You need your trees to be vertical’ she remarks, but the wild plum ‘continues / to grow undeterred, quietly collecting / birdsong in its phloem, / tucking it away in bright sharp notes.’

Not all of these poems worked for me. The last two stanzas of ‘Two men and a hornet’s nest’ seemed to be unrelated to the rest of the poem and thereby weakened its force. The abrupt shift in ‘Margaret’ does not, for me, fit easily with the first three stanzas describing a garden in neglect even though I appreciate that, the way it is titled, ‘Margaret’ is the subject of the poem.

Picking my way through the bones and carcasses of dead animals, I also longed for more variety in the subject matter: less emphasis on the darker side of nature poetry and more on a wider appreciation of the countryside.

In an interview posted in Project on 1 May 2019, (Rye Harbour Discovery Centre), Lovell tells us about her passion for wildlife and, particularly, ornithology and how she likes to collect fossils and found objects. This attention to detail is clearly made manifest in her writing and is one of her many strengths as a writer.