Poetry review – ALONENESS IS A MANY-HEADED BIRD: Wendy Klein finds a collaborative collection by Rosie Jackson and Dawn Gorman to be compulsive reading

Aloneness is a Many-Headed Bird

Rosie Jackson & Dawn Gorman

The Hedgehog Poetry Press, 2020

ISBN 97819134994

24pp £5.00

Aloneness is a Many-Headed Bird

Rosie Jackson & Dawn Gorman

The Hedgehog Poetry Press, 2020

ISBN 97819134994

24pp £5.00

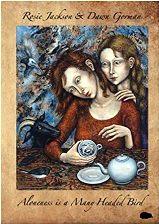

When two poetry stars like Rosie Jackson and Dawn Gorman get together to talk about what it means to be a woman ageing in 2020, it is bound to be a treat. They seem to lean in together over the kitchen table, like the two women reading tea leaves, as portrayed in the perfect cover image by artist Gina Litherland. Jackson who has several collections behind her, is no beginner to collaborative work as evidenced by her most recent acclaimed collection, Two Girls and a Beehive with the poet, Graham Burchell, which focuses on the lives of Stanley Spencer and his first wife, Hilda Carline Spencer. Gorman is also a veteran in the poetry world, long-time presenter of the reading series ‘Words and Ear’s in Bradford-on-Avon. Her brilliant pamphlet Instead, Let Us Say was winner of the Brian Dempsey Memorial Prize, and her collaborative film poems have been shown at film festivals, including the Cannes Short Film Festival.

There is a word that comes from Hebrew: tachlit or tachlis. Originally it meant ‘the main point.’ ‘Let’s talk tachlis’, get down to brass tacks, can reflect a heated session in the Knesset or to two women talking with stunning frankness about their life experiences and what the world is like for them at their age right now.

Jackson sets the tone in the opening poem ‘Treadmill’. In measured, perfectly controlled long-line couplets (one of my favourite formats, I must confess), she writes of that old constant between bodies: sex:

(…) Can anything lift the soul

into rapture the way love-making can?

though she hastens to add, ‘Not that sex should be the measure of anything’, noting how often it is, that we ‘whittle years off’ our ages with exercise and make-up, closing with an acknowledgement and a question:

But the treadmill is running faster than I can run,

each day a scramble up the chute that tips us towards landfill.

How can we age gracefully in a culture that makes death the enemy?

How indeed? This, I feel, is the essence of the book, the theme the poets return to in subsequent poems, never pulling their punches, their language at once candid and lyrical, the poems alternating one on one throughout the book. The second poem by Gorman, builds on the theme of the previous piece: ‘Truth is a Wild Thing’. Musing on love and death, she opens with:

When I am gone (i.e. dead?, my ?), you will find me here

where swallows swoop over dandelion clocks

in the meadow and small winged things

dip and bob above the water in the trough.

The register is meditative as she muses on what she will/might miss as she ages, ultimately dies: ‘Will I still love (or even make love –italics mine) at all?’ She has come to the meadow as a break from writing

and to stock up with – what is it?

A kind of truth I am hungry for these days

That kind: a truth with empathy that comes with age:

I am as gentle with the woodlouse

ravelled in pet hair on my kitchen floor

as with the no-chance man who turns up

for the date, all hope, new jeans and Eau Sauvage. (ready for sex/love or both, I ask)

I imagined the conversation taking place in lockdown with no kitchen table, no teapot, no thoughtful silences, no knowing smiles. What unfolds is like a natural conversation in verse between the two poets. Gorman’s is set out mainly in block form, with a single exception, while Jackson’s progresses in elegant long-lined couplets, each responding to the other’s utterances via email, tachlis, then reconsidered, revised, and ordered. The process is so intimate the reader might be a fly on the wall. Fortunate fly.

No subject is taboo as they address their backgrounds their relationships with their parents, with men, with their professional lives and choices. Jackson describes how her parents’ relationship impacted on her relationships with men, the war between the sexes (‘The Ground We Stand On’):

Torn between the two of them, I was caught between loving men

and despising them; the dilemma compounded when I drowned

in the second wave of feminism.

As an only child myself I recognise how Gorman describes the way everything in her house was ‘order, order’ (‘It All Adds Up’) – including her birdwatcher father:

He tried to get me interested, but I hated it –

blackbirds didn’t need a name to sing

And now she regrets this:

These days, I see the wish for me to join him

was his way of trying to warm the coldness

between us, and feel a rush of regret,

Jackson considers being ‘good enough’ daughters, relating with stark candour, the incident of her father’s death (‘Floored’), where a neighbour appearing to comfort her, took advantage of her sexually:

…held me close

in what I thought was sympathy, then laid me on the floor –

it was uncarpeted – and fucked the shock of the news

and the shock of the sex into me so it never left

and I can never think of my father’s death

without feeling unclean. I feel sick as I write this down.

Both poets seem to speak their stories ‘out loud’ writing them down for the first time in what could be described as catharsis, that unfortunate label which haunts poetry and poets who write in a manner often described disparagingly as ‘confessional.’ I do not like that label, but if this is confession in any way, it is confession as art unfolding artlessly. While a student, Gorman recounts a lucky escape from a predatory date who ‘leaps like a lynx on top of her’, then whispers in her ear, I want to squeeze all the air out of you. (‘Running’)

Over the Jackson/Gorman kitchen table, stories of unwelcome masculine forcefulness go beyond the contemporary attitudes towards ‘me too.’ More is a stake here than the war between the sexes, and nobody gets off lightly in the journey through life and love with its inevitable ending, death. In ‘The Light We Can’t See’, Jackson writes following the death of a friend that ‘The shock of mortality changes things, / makes them clearer, scissors black silhouettes (scissors – that perfect verb), against sunlight like a daguerreotype

For years I wanted to be a man, to put my feet under

their privileged table. Now I’m happy to not belong,

to spend my time wresting mercy from its opposite,

New love is found in ‘Yet’, by Jackson:

and though fears rise like mosquitoes from wetlands,

I’m determined to take each hour in its own wonder.

There are no undiluted happy endings here, but there is an uprising of hope and connectedness, a resolution to recognise happiness when it arrives as in the title poem by Gorman:

Happiness is something we chase

like butterflies in a meadow

even when it’s right there in our net.

It arrives again in a poem by Jackson, ‘Better than Angels’:

Even as being in a body gets harder, we have to let ourselves

be worn away, dissolve, till we are more river than rock.

This seems to be a summing up: both poets embrace aloneness without pleading loneliness – more river than rock.

There is risk for the reviewer in loving a book too much, focusing on all the luscious detail, suspending the critical brain. I hope that has not been the case here as there is nothing I can find not to praise. The balance between the harrowing and the illuminating is perfect. The writing is clean, finely-honed, and rich in imagery. There is nothing I can add to what is already contained in this little book: no clever observations, neat turns of phrase. To quote from it extensively, as I have done, is to allow it to review itself. Essential reading.

Jan 20 2021

London Grip Poetry Review – Rosie Jackson & Dawn Gorman

Poetry review – ALONENESS IS A MANY-HEADED BIRD: Wendy Klein finds a collaborative collection by Rosie Jackson and Dawn Gorman to be compulsive reading

When two poetry stars like Rosie Jackson and Dawn Gorman get together to talk about what it means to be a woman ageing in 2020, it is bound to be a treat. They seem to lean in together over the kitchen table, like the two women reading tea leaves, as portrayed in the perfect cover image by artist Gina Litherland. Jackson who has several collections behind her, is no beginner to collaborative work as evidenced by her most recent acclaimed collection, Two Girls and a Beehive with the poet, Graham Burchell, which focuses on the lives of Stanley Spencer and his first wife, Hilda Carline Spencer. Gorman is also a veteran in the poetry world, long-time presenter of the reading series ‘Words and Ear’s in Bradford-on-Avon. Her brilliant pamphlet Instead, Let Us Say was winner of the Brian Dempsey Memorial Prize, and her collaborative film poems have been shown at film festivals, including the Cannes Short Film Festival.

There is a word that comes from Hebrew: tachlit or tachlis. Originally it meant ‘the main point.’ ‘Let’s talk tachlis’, get down to brass tacks, can reflect a heated session in the Knesset or to two women talking with stunning frankness about their life experiences and what the world is like for them at their age right now.

Jackson sets the tone in the opening poem ‘Treadmill’. In measured, perfectly controlled long-line couplets (one of my favourite formats, I must confess), she writes of that old constant between bodies: sex:

though she hastens to add, ‘Not that sex should be the measure of anything’, noting how often it is, that we ‘whittle years off’ our ages with exercise and make-up, closing with an acknowledgement and a question:

How indeed? This, I feel, is the essence of the book, the theme the poets return to in subsequent poems, never pulling their punches, their language at once candid and lyrical, the poems alternating one on one throughout the book. The second poem by Gorman, builds on the theme of the previous piece: ‘Truth is a Wild Thing’. Musing on love and death, she opens with:

The register is meditative as she muses on what she will/might miss as she ages, ultimately dies: ‘Will I still love (or even make love –italics mine) at all?’ She has come to the meadow as a break from writing

That kind: a truth with empathy that comes with age:

I imagined the conversation taking place in lockdown with no kitchen table, no teapot, no thoughtful silences, no knowing smiles. What unfolds is like a natural conversation in verse between the two poets. Gorman’s is set out mainly in block form, with a single exception, while Jackson’s progresses in elegant long-lined couplets, each responding to the other’s utterances via email, tachlis, then reconsidered, revised, and ordered. The process is so intimate the reader might be a fly on the wall. Fortunate fly.

No subject is taboo as they address their backgrounds their relationships with their parents, with men, with their professional lives and choices. Jackson describes how her parents’ relationship impacted on her relationships with men, the war between the sexes (‘The Ground We Stand On’):

As an only child myself I recognise how Gorman describes the way everything in her house was ‘order, order’ (‘It All Adds Up’) – including her birdwatcher father:

And now she regrets this:

Jackson considers being ‘good enough’ daughters, relating with stark candour, the incident of her father’s death (‘Floored’), where a neighbour appearing to comfort her, took advantage of her sexually:

Both poets seem to speak their stories ‘out loud’ writing them down for the first time in what could be described as catharsis, that unfortunate label which haunts poetry and poets who write in a manner often described disparagingly as ‘confessional.’ I do not like that label, but if this is confession in any way, it is confession as art unfolding artlessly. While a student, Gorman recounts a lucky escape from a predatory date who ‘leaps like a lynx on top of her’, then whispers in her ear, I want to squeeze all the air out of you. (‘Running’)

Over the Jackson/Gorman kitchen table, stories of unwelcome masculine forcefulness go beyond the contemporary attitudes towards ‘me too.’ More is a stake here than the war between the sexes, and nobody gets off lightly in the journey through life and love with its inevitable ending, death. In ‘The Light We Can’t See’, Jackson writes following the death of a friend that ‘The shock of mortality changes things, / makes them clearer, scissors black silhouettes (scissors – that perfect verb), against sunlight like a daguerreotype

New love is found in ‘Yet’, by Jackson:

There are no undiluted happy endings here, but there is an uprising of hope and connectedness, a resolution to recognise happiness when it arrives as in the title poem by Gorman:

It arrives again in a poem by Jackson, ‘Better than Angels’:

This seems to be a summing up: both poets embrace aloneness without pleading loneliness – more river than rock.

There is risk for the reviewer in loving a book too much, focusing on all the luscious detail, suspending the critical brain. I hope that has not been the case here as there is nothing I can find not to praise. The balance between the harrowing and the illuminating is perfect. The writing is clean, finely-honed, and rich in imagery. There is nothing I can add to what is already contained in this little book: no clever observations, neat turns of phrase. To quote from it extensively, as I have done, is to allow it to review itself. Essential reading.