Poetry Review – LIMINAL: Adele Ward reviews Laura Fusco’s collection translated from the Italian by Caroline Maldonado

Liminal

Laura Fusco

Translated by Caroline Maldonado

Smokestack Books

ISBN 978-1916139251

88 pp £7.99

Liminal

Laura Fusco

Translated by Caroline Maldonado

Smokestack Books

ISBN 978-1916139251

88 pp £7.99

The back cover tells us ‘there are nearly 70 million refugees on the planet today’ and it’s not surprising that poets have been drawn to this theme. However, it’s a difficult subject to address in poetry without preaching or becoming sentimental, without falling into the traps political poetry can lay. Italian poets have been particularly strong in writing about refugees, no doubt due to their close experience of migrants arriving on their shores.

Laura Fusco’s poems are the best I’ve read on this subject and they lend themselves to translation, skilfully achieved in this collection by Caroline Maldonado who has also co-translated (along with Allen Prowle) a selection of poems by Rocco Scotellaro. I keep that book on my bedside table, and give credit to the publisher for doing such a fine job of presenting the poems in both Italian and English on facing pages for the many readers who enjoy bilingual texts.

A standout poem for me, in a collection where every poem deserves its place, is ‘Il pianoforte bianco’ (‘The white piano’). The settings throughout are refugee camps or temporary accommodation and this poem is no different; but the piano is an effective symbol of displacement and its arrival also shows the way art and film-making often exploit the suffering of others.

The opening lines present this surreal image and the cinematic theme:

Il pianoforte bianco scende dal camioncino,

come le porte del film di Parajanov in mezzo al nulla,

all’erba rada rada e alle tende

The white piano’s lowered from the pick-up

like the doors in Parajanov’s film in the midst of nothing,

to spindly grass and tents

This is not just a striking image: it also chimes with the repeated theme of refugees being constantly watched, filmed and included in documentaries and news stories. Whenever a piano is placed somewhere public, somebody will step forward and play, which also happens in the poem – although this has been carefully planned:

La ragazza siriana lo suona per il progetto di Ai Weiwei

peccato che lo faccia per un progetto che stanno filmando e che

lo riporteranno via tra un’ora

The Syrian girl is playing it for Ai Weiwei’s project.

Pity she’s doing it for a project they’re filming and they’ll take it away

again in an hour’s time

Not many poets use this kind of understated irony and it’s a style I especially appreciate – it makes the film-makers’ lack of empathy for the Syrian girl more shocking than sentimentality or an angry rant could communicate. All of us are complicit in this exploitation, including great artists as well as tabloid journalism, and including the audiences who watch.

There are moments of beauty captured in these poems, including the woman on the stairs in ‘We Need to Pass’ – the Italian version also has the title in English, as the titles and content of the poems share the multilingual voices of the refugees and the communities they move to:

Un’altra è su un cartone per le scale.

Si tiene alla ringhiera,

seduta sul gradino.

La ringhiera la incornicia come una foto.

Another’s on a piece of cardboard on the stairs.

She supports herself against the railing

sitting on the step.

The railing frames her like a photo.

Beautiful though this image is, we then learn why she is traumatised into holding her place while others need to get by on the stairs:

Dicono che le è morto adosso il ragazzo,

è stata violentata,

gettata al largo e ha nuotato per miglia.

They say a lad died on top of her,

she was raped,

thrown offshore and that she swam for miles.

The poems cover many details of the refugee experience in these fragmented images that work together in a cinematic technique, creating striking visual effects as well as letting us hear the words of the people, letting them take centre stage. Along with the words of the refugees in the titles and the body of the poems, the poet includes the text of graffiti, banners and songs.

There is also joy in the collection, with music a repeated theme as both young and old listen to traditional and new songs. At night there are traditional lullabies heard in the camps, while the young start to adapt and fit into new communities by taking on the clothes and popular culture, including music and dance.

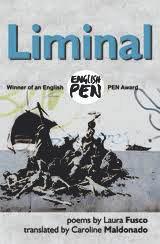

Liminal won an award from the English Pen ‘Pen Translates’ programme, and deservedly so. It’s a well-produced book, with a striking cover featuring a mural by Banksy that appeared on a street in Calais but was painted over by local residents. Based on Théodore Géricault’s painting ‘The Raft of the Medusa’ it shows refugees crowded onto a broken raft struggling to catch the attention of a passing ship.

At 88 pages this is a long collection so there are plenty of poems to read in English for those who don’t understand the Italian, while the bilingual approach means those who read both languages can enjoy and compare the original writing.

Jan 28 2021

London Grip Poetry Review – Laura Fusco

Poetry Review – LIMINAL: Adele Ward reviews Laura Fusco’s collection translated from the Italian by Caroline Maldonado

The back cover tells us ‘there are nearly 70 million refugees on the planet today’ and it’s not surprising that poets have been drawn to this theme. However, it’s a difficult subject to address in poetry without preaching or becoming sentimental, without falling into the traps political poetry can lay. Italian poets have been particularly strong in writing about refugees, no doubt due to their close experience of migrants arriving on their shores.

Laura Fusco’s poems are the best I’ve read on this subject and they lend themselves to translation, skilfully achieved in this collection by Caroline Maldonado who has also co-translated (along with Allen Prowle) a selection of poems by Rocco Scotellaro. I keep that book on my bedside table, and give credit to the publisher for doing such a fine job of presenting the poems in both Italian and English on facing pages for the many readers who enjoy bilingual texts.

A standout poem for me, in a collection where every poem deserves its place, is ‘Il pianoforte bianco’ (‘The white piano’). The settings throughout are refugee camps or temporary accommodation and this poem is no different; but the piano is an effective symbol of displacement and its arrival also shows the way art and film-making often exploit the suffering of others.

The opening lines present this surreal image and the cinematic theme:

This is not just a striking image: it also chimes with the repeated theme of refugees being constantly watched, filmed and included in documentaries and news stories. Whenever a piano is placed somewhere public, somebody will step forward and play, which also happens in the poem – although this has been carefully planned:

Not many poets use this kind of understated irony and it’s a style I especially appreciate – it makes the film-makers’ lack of empathy for the Syrian girl more shocking than sentimentality or an angry rant could communicate. All of us are complicit in this exploitation, including great artists as well as tabloid journalism, and including the audiences who watch.

There are moments of beauty captured in these poems, including the woman on the stairs in ‘We Need to Pass’ – the Italian version also has the title in English, as the titles and content of the poems share the multilingual voices of the refugees and the communities they move to:

Beautiful though this image is, we then learn why she is traumatised into holding her place while others need to get by on the stairs:

The poems cover many details of the refugee experience in these fragmented images that work together in a cinematic technique, creating striking visual effects as well as letting us hear the words of the people, letting them take centre stage. Along with the words of the refugees in the titles and the body of the poems, the poet includes the text of graffiti, banners and songs.

There is also joy in the collection, with music a repeated theme as both young and old listen to traditional and new songs. At night there are traditional lullabies heard in the camps, while the young start to adapt and fit into new communities by taking on the clothes and popular culture, including music and dance.

Liminal won an award from the English Pen ‘Pen Translates’ programme, and deservedly so. It’s a well-produced book, with a striking cover featuring a mural by Banksy that appeared on a street in Calais but was painted over by local residents. Based on Théodore Géricault’s painting ‘The Raft of the Medusa’ it shows refugees crowded onto a broken raft struggling to catch the attention of a passing ship.

At 88 pages this is a long collection so there are plenty of poems to read in English for those who don’t understand the Italian, while the bilingual approach means those who read both languages can enjoy and compare the original writing.