Dec 28 2020

London Grip Poetry Review – Adnan Al-Sayegh

Poetry review – LET ME TELL YOU WHAT I SAW: Ruth Valentine reviews a well-made selection of Adnan Al-Sayegh’s vivid and disturbing poetry

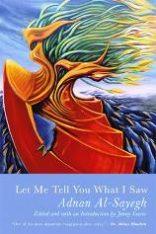

Let Me Tell You What I Saw Adnan Al-Sayegh: Edited & with an introduction by Jenny Lewis Seren Books, 2020 ISBN 9781781726020 pp.213 £12.99

Let Me Tell You What I Saw is a bilingual selection from Adnan al-Sayegh’s 550-page poem Uruk’s Anthem, written over twelve years, between 1984 and 1996. During those years the poet was variously conscripted into the Iraqi army for the devastating Iran-Iraq war, imprisoned in a military detention centre, and living in exile, first in Sweden and now in London. The range of those personal experiences would be enough to fill more than one collection of poems; but this is a more ambitious project:

I saw the blood of slaves

on a Sumerian stone altar

the flies of ages buzzing around it

I saw time fall

from the high-rises.

I saw Khayyam

in Shiraz's bar

sipping cups of existence...

p.35

We are in ancient Uruk, the Sumerian city on the Euphrates; but equally in any modern city, and in medieval Persia with another poet, Omar Khayyam. This is an epic, but not in any narrative or chronological sense. The structure is subtle, moving from visions of historic and modern events, through exile, to an impassioned questioning of the country’s destiny. It is an intuitive account of the poet’s existence in the context of history: the history of his country of origin, of world culture, of its own moment. The narrator tells us ‘I saw’, ‘I heard’, ‘I dreamed,’ and these act as repeated jump-cuts between one era and another, one place and another, between cultures. We meet Tiresias, Lorca, Hikmet; we visit, in passing, Karbala and Sarajevo; we face the interrogator across a table.

In an afterword, we are told that Jenny Lewis worked with both Al-Sayegh and the Palestinian-Lebanese poet Ruba Abughaida, to create a musicality equivalent to the original. Line-lengths vary, at times terse, at times into prose-poem. Layout on the page creates pauses, silences, delayed shocks:

I shouted sadly: O my country

so the walls of the cell shook: Oh!!

And the guards shared the scraps of letters

and hidden tobacco in the blanket of

one of the prisoners

before she was executed.

p.95

It’s the detail that assures us that this is more than a rhetorical device: the tobacco hidden in the blanket, the callous greed of the guards.

One repeated motif is the General, the autocratic ruler of any era.

What have you done to us, O General who is passionate about mazes?

What did you do to this country?

It can find no trees to lean on, other than your sword,

and nothing to water it

but

your piss.

p.75

The narrator is never simply a victim, whatever pains he undergoes. He and his compatriots, perhaps all of us, are made complicit. Here he conjures a sniper, and his own reciprocal gun:

...each is carrying the death of the other in his palms... do you hear me you doltish sniper:

each carries between his gripping fingers and the gun trigger, a widow and an orphan.

pp.117/119

Life, nevertheless, is more than war and oppression; it is also what can be salvaged from war and oppression. There is love and desire; there is the fact of writing:

It's for me to turn the millstone of words to grind my soul for a girl drinking coffee in the morning, to see other than the blue of this sky, a sky for your shining eyes

behind the iron of prisons and melancholy songs.

p.49

This is a book to dwell on, to deepen one’s understanding reading by reading. The introduction, by Jenny Lewis, and the copious footnotes, help the non-Iraqi reader to gather knowledge of the poem’s context and the poet’s wide-ranging cultural references, absorb them and return to the text itself. I don’t know Arabic and can’t judge the translation in terms of accuracy or faithfulness of tone; but my concentration was very rarely broken by an awkward phrasing. The imagery, the sensory detail, will in any case speak beyond the limits of translation: the war ‘smokes you like a cigarette;’ ‘we carry our mats like a country/and fold them quickly/whenever the security forces raid us.’

Hearing Adnan Al-Sayegh read his work in its original language is a pleasure to be sought out, whether or not you know Arabic. In the absence of live readings, his own website is a starting-point: http://adnanalsayegh.com/eng/. Meanwhile, this monumental work of collaborative translation is an exciting, disturbing, enlightening introduction.

31/12/2020 @ 18:17

Thank you Ruth. What an intriguing review, and what haunting extracts you’ve quoted here; you’ve led me to want to explore further.