Poetry review – SHIPWRECKED: Alex Josephy browses a stimulating and linguistically adventurous collection by Wendy Holborow

Shipwrecked

Wendy Holborow

Lucy Quieter Press

ISBN 979-8602156300

93pp £12

Shipwrecked

Wendy Holborow

Lucy Quieter Press

ISBN 979-8602156300

93pp £12

It’s two years since I re-viewed Wendy Holborow’s An Italian Afternoon for Envoi magazine. I very much appreciated her evocation of place and her skilful use of varied forms to trace a narrative set in Italy, my own adopted country. Since then she has published several collections, most notably Janky Tuk Tuks, a sequence set in India and Africa. Reading her latest book in these changed times, it was a pleasure to rediscover Holborow’s infectious interest in words and language, this time played out across darker emotional territory.

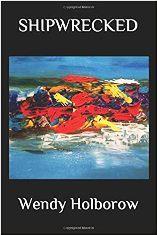

The jacket image is a Holborow oil painting, its bold colours and confident brush strokes well suited to the poet’s themes; it looks like a wrecked ship going down (or perhaps staying afloat?) in a defiant blaze. The techniques and conventions of painting recur metaphorically throughout the collection, as in ‘Sponged Out’, where a rejected woman

…goes to where the cypress trees are black

and stripe the landscape like brush strokes…

…and she is sponged out of all vibrant compositions.

Many of these poems have an interestingly dual focus; Holborow deals with loss, death, betrayal and abandonment, while she also gives rein to a fascination with obscure diction. In ‘Iced Over’, for example, a spurned lover complains of

unmelting love

tugged into the esurient

freezing sea

As with many words in this collection, I had to resort to the dictionary to learn that ‘esurience’ is an archaic word for a greedy kind of hunger. Later in the same poem, the lovers’ life is described as ‘immiscible’ (incapable of mixing or attaining homogeneity, according to Merriam-Webster). What are these words doing in a modern, otherwise fairly colloquial poem, I wondered? Are they a form of self defence – a way for the disappointed lover to gain higher ground? It is as if the long, unfamiliar words used in many of the poems provide a kind of bulwark against pain.

Somewhere near the centre of the collection there is a delightful sequence of four poems that specifically revel in Holborow’s sesquipedalian tendencies. A definition is kindly given as a gloss: ‘Sesquipedalian (A word that’s very long and multisyllabic)’ – though could it be one without the other, I wondered? Further investigation was irresistible, and in the event it added to my appreciation of the poet’s self irony; I discovered other definitions, including ‘given to the overuse of very long words’. The slightly lighter tone of the four poems in this sequence offers a welcome counterpoint to earlier meditations on loss and grieving. The poet threads a delicate narrative across four uncommon words; my favourite is ‘Crytoscophilia – the urge to look inside people’s windows.’ Here, the long words seem to hint at a vain attempt to communicate or make a connection; the poet is a peeping Tom (‘the inquisitive, lonely me’), excluded from ordinary conversations, perhaps because of the distancing effect of grief.

As in her earlier work, Holborow employs a range of traditional poetic forms, as well as free verse and visual effects. On the theme of death (of parents and of other friends and companions) there’s a ‘Pantoum for the Dead’, a touching ‘Triolet of Dance’, a prose poem taking courage from Dylan Thomas (‘I bow before shit, seeing the family likeness in the old familiar faeces’), which challenges the ‘taboo to think of one’s parents having sex’. There’s a villanelle ‘I Bask in your Disdain’, a witty idea which for me becomes weighed down by the form’s hunger for rhyme. On the whole I found the simpler free verse poems the most moving, for instance the slender lines and pared-down imagery in ’Trees Outside Montuschi Ward’:

Today it is clement, but cold.

The trees are still,

stark sticks of charcoal

against a grey canvas of sky

as snow ticks the windowpanes.

I love the way that word ‘ticks’ quietly conveys both fragility and a wintery serenity.

Holborow also plays with concrete effects, layout, words within words, and multiple meanings. At times, I found the poems based on wordplay a little overladen with their own cleverness – as if taking it that step further becomes a dangerous temptation. For instance, in ‘Chercher le Mot Juste’,

poetry is I am(bic) (m)etre I am(b) what I(amb)

enjamb

ment (meant)

I did appreciate this approach, though, in other poems such as ‘The Dance’ where a partner’s inconstancy is mirrored in the unreliability of words:

childhood sweethearts –

two red he(art)s instead of the br(own) upon black

black for you who cheated

brown for me the conspirator

conscripted to y(our) love

Holborow’s canvas is broad, drawing on cultural references from Ozymandias to Ibsen, David Hockney to Fernando Pessoa. There are poems on war and displacement, and on altered states brought on for instance by senility or ‘swings in mood from grey mania/to the depths of the blues’. These don’t always land where you might expect, as in the final lines of ‘Medication’:

The medication takes her

up spiral staircases of space

to an errant jubilation.

This makes reading Shipwrecked a stimulating and on the whole uplifitng experience. There are many trails to follow, and a consoling sense of how the arts can offer companionship, virtually if not in person, in times of isolation or difficulty. I loved the three poems for the Portuguese poet Pessoa. What does Pessoa mean by ‘doored’? To me it’s a great example of negative capability.

How he wonders if the people

across the road, in that room

are as lonely as he is,

so he sits to write a poem

for his Ophelia that

love’s large power is also doored.

Alex Josephy

Oct 14 2020

London Grip Poetry Review – Wendy Holborow

Poetry review – SHIPWRECKED: Alex Josephy browses a stimulating and linguistically adventurous collection by Wendy Holborow

It’s two years since I re-viewed Wendy Holborow’s An Italian Afternoon for Envoi magazine. I very much appreciated her evocation of place and her skilful use of varied forms to trace a narrative set in Italy, my own adopted country. Since then she has published several collections, most notably Janky Tuk Tuks, a sequence set in India and Africa. Reading her latest book in these changed times, it was a pleasure to rediscover Holborow’s infectious interest in words and language, this time played out across darker emotional territory.

The jacket image is a Holborow oil painting, its bold colours and confident brush strokes well suited to the poet’s themes; it looks like a wrecked ship going down (or perhaps staying afloat?) in a defiant blaze. The techniques and conventions of painting recur metaphorically throughout the collection, as in ‘Sponged Out’, where a rejected woman

Many of these poems have an interestingly dual focus; Holborow deals with loss, death, betrayal and abandonment, while she also gives rein to a fascination with obscure diction. In ‘Iced Over’, for example, a spurned lover complains of

As with many words in this collection, I had to resort to the dictionary to learn that ‘esurience’ is an archaic word for a greedy kind of hunger. Later in the same poem, the lovers’ life is described as ‘immiscible’ (incapable of mixing or attaining homogeneity, according to Merriam-Webster). What are these words doing in a modern, otherwise fairly colloquial poem, I wondered? Are they a form of self defence – a way for the disappointed lover to gain higher ground? It is as if the long, unfamiliar words used in many of the poems provide a kind of bulwark against pain.

Somewhere near the centre of the collection there is a delightful sequence of four poems that specifically revel in Holborow’s sesquipedalian tendencies. A definition is kindly given as a gloss: ‘Sesquipedalian (A word that’s very long and multisyllabic)’ – though could it be one without the other, I wondered? Further investigation was irresistible, and in the event it added to my appreciation of the poet’s self irony; I discovered other definitions, including ‘given to the overuse of very long words’. The slightly lighter tone of the four poems in this sequence offers a welcome counterpoint to earlier meditations on loss and grieving. The poet threads a delicate narrative across four uncommon words; my favourite is ‘Crytoscophilia – the urge to look inside people’s windows.’ Here, the long words seem to hint at a vain attempt to communicate or make a connection; the poet is a peeping Tom (‘the inquisitive, lonely me’), excluded from ordinary conversations, perhaps because of the distancing effect of grief.

As in her earlier work, Holborow employs a range of traditional poetic forms, as well as free verse and visual effects. On the theme of death (of parents and of other friends and companions) there’s a ‘Pantoum for the Dead’, a touching ‘Triolet of Dance’, a prose poem taking courage from Dylan Thomas (‘I bow before shit, seeing the family likeness in the old familiar faeces’), which challenges the ‘taboo to think of one’s parents having sex’. There’s a villanelle ‘I Bask in your Disdain’, a witty idea which for me becomes weighed down by the form’s hunger for rhyme. On the whole I found the simpler free verse poems the most moving, for instance the slender lines and pared-down imagery in ’Trees Outside Montuschi Ward’:

I love the way that word ‘ticks’ quietly conveys both fragility and a wintery serenity.

Holborow also plays with concrete effects, layout, words within words, and multiple meanings. At times, I found the poems based on wordplay a little overladen with their own cleverness – as if taking it that step further becomes a dangerous temptation. For instance, in ‘Chercher le Mot Juste’,

I did appreciate this approach, though, in other poems such as ‘The Dance’ where a partner’s inconstancy is mirrored in the unreliability of words:

Holborow’s canvas is broad, drawing on cultural references from Ozymandias to Ibsen, David Hockney to Fernando Pessoa. There are poems on war and displacement, and on altered states brought on for instance by senility or ‘swings in mood from grey mania/to the depths of the blues’. These don’t always land where you might expect, as in the final lines of ‘Medication’:

This makes reading Shipwrecked a stimulating and on the whole uplifitng experience. There are many trails to follow, and a consoling sense of how the arts can offer companionship, virtually if not in person, in times of isolation or difficulty. I loved the three poems for the Portuguese poet Pessoa. What does Pessoa mean by ‘doored’? To me it’s a great example of negative capability.

Alex Josephy