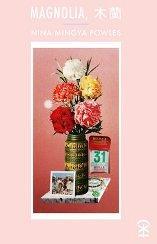

Poetry review – MAGNOLIA: D A Prince peruses an ambitious and multi-faceted debut collection by Nina Mingya Powles

Magnolia

Nina Mingya Powles

Nine Arches Press, 2020.

ISBN 978-1-911027-99-7

82 pp £9.99.

Magnolia

Nina Mingya Powles

Nine Arches Press, 2020.

ISBN 978-1-911027-99-7

82 pp £9.99.

While some collections are comfortingly easy to read, perhaps because the forms are recognisable or the subjects are on your home ground, this — at least, for me —wasn’t one of them. It didn’t confirm what’s familiar or speak to me in the way many of the poets I’ve been reading recently are writing. It pushed at language, making new rules as it went along. But that’s the point of this collection: it’s asking and shaping questions, looking for answers which cover new ground for the poet. It’s about the hunger (literal as well as metaphorical) to know more and, ultimately, it’s very satisfying.

First, some context. Powles comes from New Zealand and from mixed heritage. Her mother was from Malaysia where Powles recently spent eighteen months, studying Mandarin and writing poems and prose as she learned its languages, flavours, culture, colours and sounds. After moving to London in 2018 she found the initial shape of a collection within these writings. The magnolia — mulan in Chinese — is the official flower of Shanghai; hence the collection’s title. A poem centred on Mulan — the 1998 film and not the recent Disney re-make — provides the starting point for the collection.

This first poem (with the long title ‘Girl Warrior, or: watching Mulan (1998) in Chinese with English subtitles’) stretches over seven sections. It lays out not only some of the themes which Powles will keep returning to but also — and more significantly — her style, or voice, or breath, or what name we give to how she draws words together to make these poems on the page. The lines, marked up for breath, take their time; she looks both inward and outward, to the screen and back into herself, making comparisons between herself and the perfect female Chinese warrior on screen —

… / a Disney

princess kneeling in the smoke-coloured dark / with straight hair /

thin waist / hardly any breasts

unlike me with my thick legs / and too much hair that doesn’t stay

Isn’t that, deep down, how we’ve all watched films, longing to live up to an impossible ideal? Powles is also using the film as a way into its language, admitting that ‘I understand only some of the words’ before opening herself to those she does understand —

In Chinese one word can lead you out of the dark / then back into it / in a single breath

Shut off the light / as my mother and other Chinese mothers say

Now open it

Her long lines, marked for breaks but written as a continuous line, are characteristic. They read as though her voice is balancing along a footbridge between one language and another, between her familiar English and the Chinese she is reaching into. As we read we see how she is learning; she gives us unfamiliar words and Chinese characters in context. The richly physical and visual context is inclusive; we start to encounter it with her. In ‘Breakfast in Shanghai’ Powles shows us four mornings — coldest smog, a downpour, homesickness, late spring — with the foods to match. To google, for example, b?ozi or zòngzi, would be to loose the totality of each morning — its texture, colour, rituals and rhythms. It ends —

Bright skins and

leaves sucked clean, my hands smelling tea-sweet. Something

inside me uncurling. A hunger that won’t go away.

Hunger and food are complementary and they lead to learning the right words. In ‘Black vinegar blood’, a prose poem in three stanzas, the first section — entirely in English — sets up the theme:

For so long I didn’t know how to ask for soy sauce so I dipped

my dumplings in whatever was on the table, usually watered-

down rice vinegar in a tiny ceramic teapot, see-through but

strong enough to make my lips pucker. It dries black and sweet

on my skin.

But then, slowly, the Chinese characters enter, naming the food but not translated. This is language at work, taking its proper place, naturally. It doesn’t matter that I can’t read (or google) for an exact translation; my understanding is being taken into the meal, savouring those parts I can understand, and sharing Powles’ own sensory learning to the point where it’s the Chinese word that comes first to her mind.

She uses colour, too, to speak directly to the reader. Powles may be writing of places unfamiliar to many readers but the way she piles up colours brings the exotic into close focus. It’s a risky way to write a poem but within the wide range of sensations Powles evokes, it works; her use of colours across all the poems adds to the coherence of the collection. In ‘Two portraits of home; after Werner’s Nomenclature of Colours, 1814)’ she places two ‘colour’ poems on facing pages, letting the colours move from memories of New Zealand to those of Shanghai, and overlap. The first [IMG_098] includes New Zealand’s trees (the kowhai is the country’s unofficial national tree) and bird (the fantail)

distant-forest green feijoa tree green

kowhai-petal-yellow

fantail-feather cream

volcanic grey

while the second ([IMG_227]) sets ‘magnolia-leaf-green-black’ against New Zealand’s palette before the kaleidoscopic Chinese colours of the ending. It’s a merging of visual memory; a New Zealand bird (the t??) slips in among the city-life colours of Shanghai—

lower wings of tiger moth red lantern-festival red

mooncake-wrapper gold t??-feather iridescent green

electric billboard blue neon neon green high-definition silver

shanghai-taxi blue reflected gasoline blue

grass-jelly black

wet-cormorant black nightriver black

Powles is attentive to the patterning of words across the pages, as though allowing them to breathe. The visual contrast with her prose poems subliminally invites different speeds of reading and with that a mirror of how different cultures are encountered.

‘Field notes in a downpour’, a poem in eight short parts, has a section to itself, exploring the suggestive links within Chinese characters. So her mother’s name is made of both ‘rain’ and ‘language’, combining as ‘multi-coloured clouds’, allowing Powles to follow the suggestions—

There are so many things I am trying to hold together. I write then down each day to stop them

from slipping. Mouthfuls of rain, the blue undersides of clouds, her hydrangeas in the dark.

The penultimate (seventh) part moves from the rain/water/cloud suggestions contained in some characters to the more personal character connected to her own name in Chinese—

the cry of animals and insects, rhymes with tooth, which rhymes with precipice,

which rhymes with the first part of my Chinese name.

I am full of nouns and verbs; I don’t know how to live any other way.

[ ]

Certain languages contain more kinds of rain than others, and I have eaten them all.

There’s a range of cultural reference rising out of her own enthusiasms — film and film-makers, Japanese spirit figures, the New Zealand writer Robin Hyde, the Chinese writer Eileen Chang. It’s an ambitious collection, worth its place on the short-list for the Forward First Collection, and one that repays the reader’s full attention and careful listening.

DA Prince

Oct 12 2020

London Grip Poetry Review – Nina Mingya Powles

Poetry review – MAGNOLIA: D A Prince peruses an ambitious and multi-faceted debut collection by Nina Mingya Powles

While some collections are comfortingly easy to read, perhaps because the forms are recognisable or the subjects are on your home ground, this — at least, for me —wasn’t one of them. It didn’t confirm what’s familiar or speak to me in the way many of the poets I’ve been reading recently are writing. It pushed at language, making new rules as it went along. But that’s the point of this collection: it’s asking and shaping questions, looking for answers which cover new ground for the poet. It’s about the hunger (literal as well as metaphorical) to know more and, ultimately, it’s very satisfying.

First, some context. Powles comes from New Zealand and from mixed heritage. Her mother was from Malaysia where Powles recently spent eighteen months, studying Mandarin and writing poems and prose as she learned its languages, flavours, culture, colours and sounds. After moving to London in 2018 she found the initial shape of a collection within these writings. The magnolia — mulan in Chinese — is the official flower of Shanghai; hence the collection’s title. A poem centred on Mulan — the 1998 film and not the recent Disney re-make — provides the starting point for the collection.

This first poem (with the long title ‘Girl Warrior, or: watching Mulan (1998) in Chinese with English subtitles’) stretches over seven sections. It lays out not only some of the themes which Powles will keep returning to but also — and more significantly — her style, or voice, or breath, or what name we give to how she draws words together to make these poems on the page. The lines, marked up for breath, take their time; she looks both inward and outward, to the screen and back into herself, making comparisons between herself and the perfect female Chinese warrior on screen —

Isn’t that, deep down, how we’ve all watched films, longing to live up to an impossible ideal? Powles is also using the film as a way into its language, admitting that ‘I understand only some of the words’ before opening herself to those she does understand —

Her long lines, marked for breaks but written as a continuous line, are characteristic. They read as though her voice is balancing along a footbridge between one language and another, between her familiar English and the Chinese she is reaching into. As we read we see how she is learning; she gives us unfamiliar words and Chinese characters in context. The richly physical and visual context is inclusive; we start to encounter it with her. In ‘Breakfast in Shanghai’ Powles shows us four mornings — coldest smog, a downpour, homesickness, late spring — with the foods to match. To google, for example, b?ozi or zòngzi, would be to loose the totality of each morning — its texture, colour, rituals and rhythms. It ends —

Hunger and food are complementary and they lead to learning the right words. In ‘Black vinegar blood’, a prose poem in three stanzas, the first section — entirely in English — sets up the theme:

But then, slowly, the Chinese characters enter, naming the food but not translated. This is language at work, taking its proper place, naturally. It doesn’t matter that I can’t read (or google) for an exact translation; my understanding is being taken into the meal, savouring those parts I can understand, and sharing Powles’ own sensory learning to the point where it’s the Chinese word that comes first to her mind.

She uses colour, too, to speak directly to the reader. Powles may be writing of places unfamiliar to many readers but the way she piles up colours brings the exotic into close focus. It’s a risky way to write a poem but within the wide range of sensations Powles evokes, it works; her use of colours across all the poems adds to the coherence of the collection. In ‘Two portraits of home; after Werner’s Nomenclature of Colours, 1814)’ she places two ‘colour’ poems on facing pages, letting the colours move from memories of New Zealand to those of Shanghai, and overlap. The first [IMG_098] includes New Zealand’s trees (the kowhai is the country’s unofficial national tree) and bird (the fantail)

distant-forest green feijoa tree green kowhai-petal-yellow fantail-feather cream volcanic greywhile the second ([IMG_227]) sets ‘magnolia-leaf-green-black’ against New Zealand’s palette before the kaleidoscopic Chinese colours of the ending. It’s a merging of visual memory; a New Zealand bird (the t??) slips in among the city-life colours of Shanghai—

lower wings of tiger moth red lantern-festival red mooncake-wrapper gold t??-feather iridescent green electric billboard blue neon neon green high-definition silver shanghai-taxi blue reflected gasoline blue grass-jelly black wet-cormorant black nightriver blackPowles is attentive to the patterning of words across the pages, as though allowing them to breathe. The visual contrast with her prose poems subliminally invites different speeds of reading and with that a mirror of how different cultures are encountered.

‘Field notes in a downpour’, a poem in eight short parts, has a section to itself, exploring the suggestive links within Chinese characters. So her mother’s name is made of both ‘rain’ and ‘language’, combining as ‘multi-coloured clouds’, allowing Powles to follow the suggestions—

The penultimate (seventh) part moves from the rain/water/cloud suggestions contained in some characters to the more personal character connected to her own name in Chinese—

There’s a range of cultural reference rising out of her own enthusiasms — film and film-makers, Japanese spirit figures, the New Zealand writer Robin Hyde, the Chinese writer Eileen Chang. It’s an ambitious collection, worth its place on the short-list for the Forward First Collection, and one that repays the reader’s full attention and careful listening.

DA Prince