Poetry review – NEGOTIATING CAPONATA – Rennie Halstead looks at poems by Carla Scarano D’Antonio which reflect the intensity of family relationships across generations

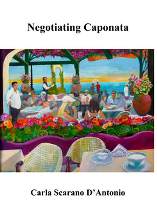

Negotiating Caponata

Carla Scarano D’Antonio

Dempsey and White 2020

ISBN 978-1-913329-22-8

£8:00

Negotiating Caponata

Carla Scarano D’Antonio

Dempsey and White 2020

ISBN 978-1-913329-22-8

£8:00

Negotiating Caponata is an enjoyable collection from Carla Scarano D’Antonio. The back cover text discusses the role of food in the book, and D’Antonio certainly weaves the opening of the collection round themes of food preparation, and the meanings and symbolism that food has in families. But don’t be drawn into too relaxed a view. The trials and tribulations of mastering Italian cuisine are nothing compared to the intricate – and sometimes painful – family relationships. These dominate the later part of the collection which is filled with an accompanying sense of loss.

In “Pajarita” D’Antonio muses on the ability of origami birds to carry her thoughts and feelings across oceans:

My thoughts are tiny ideograms

inked on wrapping paper,

hidden in the folds of my paper bird.

She envisages the paper bird:

[…] flapping across the ocean

picturing our minds touching

like two hands pressing palms

But she also wants a response. She waits ‘… for you to reshape the bird,/ send it back to me.’

“What I was leaving” introduces us to the idea of distance and departure that characterises parts of the book. Here D’Antonio remembers autumns from different years with great nostalgia. In 2014:

leaves gather in burning rust and ochre,

streaks mark the skin red:

I love their way of dying.

whilst in 2015:

the trees turn gold and vermillion

purple and burnt sienna.

Now it’s there

a few days later it’s gone,

But in 2018 the fading of the landscape in autumn brings memories of other times and places:

The full moon is ricotta cheese in a sea of blueberry juice.

Now I cook leek and potato soup,

[…]

the soup mashes in our mouths

tasting of childhood minestrone rich with curved macaroni,

our southern persistence beyond ourselves

pulsing.

The next section of the collection, ‘My Father’s Death’, has a very different and darker tone. In “Your illness” D’Antonio takes us through the pain and suffering of the dying:’ your body kept retching / bucketfuls of brown liquid / day and night.’ But the sadness for the dying is coloured by memory. The family history cannot be ignored, even at this point:

Mum held the tub under your chin

and cleaned the floor on her unsteady knees

forgetting all the past beatings and shame.

Similarly, in “Your last words” the past is not far away:

[…] you opened your eyes -

[…]

lifted an arm, tried to speak

(the last advice?

or threats if we transgressed,

but despite the mixture of pain and love in the memory, the poet-narrator

[…] opened the window to let in the mild April air

and waited in bed

listening to the silence of the night,

your body voiceless and still,

only my memory of you alive.

Following the father’s death, the poet is elected to conduct the final act. In “Dispersing your ashes” the poet asks: ‘Who else can do it?’ The final dispersion has great sadness and a touch of humour:

The ashes whirl in the wind, unstrained

mix in the roaring waves of the backwash

making it murky.

[…They] soak my skirt to the waist.

I wonder if they will leave stains,

[…]

the last specks fly and dissolve,

it lasts seconds.

But the poem expresses a desire for the final act to have a greater sense of occasion:

I wish it longer,

more solemn

conclusive in some way.

The sun is setting in a soaring blue.

The final section, ‘In Touch’ draws family memories together. First we meet “Grandad Ciccio and Grandma Orsola” in a skilfully written specular. D’Antonio creates a word picture so well that you can see the couple in your mind’s eye, as if in a sepia photograph. The couple sit ‘serene like ancient Roman statues’

with their first baby daughter on their lap.

He in grey uniform and high boots, she in black dress and hat

against a white background.

Grandad Ciccio’s ‘arm touches lightly her shoulders, / a bag made of silver-net hangs from her gloved hand.’

By the end of the collection we have a strong sense of the family, and it is fitting that “Volcano” explores the world of the mother. The poem starts quietly enough: ‘Crickets fill the lap of night,/ walls sweat the heat of the day.’ But the peace is a precursor to internal drama:

On the balcony she mumbles,

words bubble up from inside

boiling phrases she couldn’t say

to her late husband

She calls him ‘the bastard who squandered on his tart’ and complains about the daughter, ‘the bitch who calls me a crazy hag.’ But the anger and resentment is sharpened by the awareness of what she has lost. Beside the family grief, there is:

the shadow of the other man who came last night —

every night —

begs her to join him;

but it’s too late,

he’s back in America now.

And with no solution, no prospect of improving her situation, she watches as:

The city sinks into torrid August.

Sounds brood within,

murmurs beneath closed lips.

She is a sealed volcano.

I really enjoyed this collection. I confess to being a little unsure at first, when I ran into a group of recipe poems, but as soon as we started to meet the family behind the food and saw how important food was in their lives, the book came to life for me. The intensity of the family relationships is graphically captured with great sensitivity, and the sense of pain and regret that runs through the book like a watermark grounds the poems. The final poems look at the beginning of a new life, so the collection finally moves away from the trials of family life and the collection ends on a positive and upbeat note.

Rennie Halstead

Sep 23 2020

London Grip Poetry Review – Carla Scarano D’Antonio

Poetry review – NEGOTIATING CAPONATA – Rennie Halstead looks at poems by Carla Scarano D’Antonio which reflect the intensity of family relationships across generations

Negotiating Caponata is an enjoyable collection from Carla Scarano D’Antonio. The back cover text discusses the role of food in the book, and D’Antonio certainly weaves the opening of the collection round themes of food preparation, and the meanings and symbolism that food has in families. But don’t be drawn into too relaxed a view. The trials and tribulations of mastering Italian cuisine are nothing compared to the intricate – and sometimes painful – family relationships. These dominate the later part of the collection which is filled with an accompanying sense of loss.

In “Pajarita” D’Antonio muses on the ability of origami birds to carry her thoughts and feelings across oceans:

She envisages the paper bird:

But she also wants a response. She waits ‘… for you to reshape the bird,/ send it back to me.’

“What I was leaving” introduces us to the idea of distance and departure that characterises parts of the book. Here D’Antonio remembers autumns from different years with great nostalgia. In 2014:

whilst in 2015:

But in 2018 the fading of the landscape in autumn brings memories of other times and places:

The next section of the collection, ‘My Father’s Death’, has a very different and darker tone. In “Your illness” D’Antonio takes us through the pain and suffering of the dying:’ your body kept retching / bucketfuls of brown liquid / day and night.’ But the sadness for the dying is coloured by memory. The family history cannot be ignored, even at this point:

Similarly, in “Your last words” the past is not far away:

but despite the mixture of pain and love in the memory, the poet-narrator

Following the father’s death, the poet is elected to conduct the final act. In “Dispersing your ashes” the poet asks: ‘Who else can do it?’ The final dispersion has great sadness and a touch of humour:

But the poem expresses a desire for the final act to have a greater sense of occasion:

The final section, ‘In Touch’ draws family memories together. First we meet “Grandad Ciccio and Grandma Orsola” in a skilfully written specular. D’Antonio creates a word picture so well that you can see the couple in your mind’s eye, as if in a sepia photograph. The couple sit ‘serene like ancient Roman statues’

Grandad Ciccio’s ‘arm touches lightly her shoulders, / a bag made of silver-net hangs from her gloved hand.’

By the end of the collection we have a strong sense of the family, and it is fitting that “Volcano” explores the world of the mother. The poem starts quietly enough: ‘Crickets fill the lap of night,/ walls sweat the heat of the day.’ But the peace is a precursor to internal drama:

She calls him ‘the bastard who squandered on his tart’ and complains about the daughter, ‘the bitch who calls me a crazy hag.’ But the anger and resentment is sharpened by the awareness of what she has lost. Beside the family grief, there is:

And with no solution, no prospect of improving her situation, she watches as:

I really enjoyed this collection. I confess to being a little unsure at first, when I ran into a group of recipe poems, but as soon as we started to meet the family behind the food and saw how important food was in their lives, the book came to life for me. The intensity of the family relationships is graphically captured with great sensitivity, and the sense of pain and regret that runs through the book like a watermark grounds the poems. The final poems look at the beginning of a new life, so the collection finally moves away from the trials of family life and the collection ends on a positive and upbeat note.

Rennie Halstead