Poetry Review – RARE BIRDS: Angela Topping is moved and impressed by Natalie Scott’s poems about a women’s prison

Rare Birds, Voices of Holloway Prison

Natalie Scott

Valley Press

ISBN: 9781912436255

146pp £12

Rare Birds, Voices of Holloway Prison

Natalie Scott

Valley Press

ISBN: 9781912436255

146pp £12

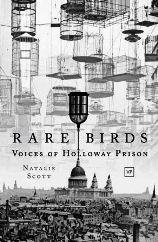

The book opens with a really helpful and concise history of Holloway prison, and there are some well-chosen epigraphs, which set the tone for Scott’s exploration of the prisoners, their crimes and their feelings about the place. The cover is stunning: a monochrome vista of London, with a sky full of empty birdcages already speaks volumes about the inmates and their stories. Added to this, the prison’s strange foundation-stone message of preserving the city of ‘evil doers’ is cleverly undercut by emboldening some of the prisoners’ letters to present the idea of a counter narrative about privilege, as most of the inmates were there for crimes caused by poverty and desperation.

Not all the voices are of women. The first poem is chillingly an advert calling people to come and see the criminals as though they were fairground exhibits. It is spoken by Major Arthur Griffiths, inspector of prisons from 1878-1896. The poem uses a fairly tight form to express his glibness. His shaming of the prisoners makes uncomfortable reading:

Now, a treat… the criminal women:

sad sisters whose outfits don’t match.

See ladies, how this one wears both

satin skirt and coarse shawl. Quite so!

The list of different sorts of sinners is strongly reminiscent of the porter’s list in Macbeth, and thus, by association, summons up the rottenness at the heart of London at that time, which encouraged the ridiculing its criminals, often only guilty of petty crimes. There is also a quite astonishing othering of ‘foreigners’. The fact that these prisoners were made to parade past more fortunate people for the purpose of humiliation is shocking. It’s a very clever way to open the book, because the reader is now firmly on the side of the inmates.

After these opening salvos, the bulk of the work is where Scott takes different women’s voices to explore their histories. She gives their names and their crimes. The research is very impressive, but even more so is what she does with her knowledge. The range of forms allows each woman to speak her own story, with the poet an invisible shaping hand behind the scenes. The narratives that emerge are compelling.

Emma Mary Bird, found guilty of assault in 1852, is represented by her description in the record books, with her imagined thoughts added by Scott, such as Sallow for her complexion, followed by the recollection ‘yesterday I only ate scraps’. 89 year old Lydia Clemens, sentenced to 7 days of hard labour for begging, hopes she’ll put on some weight in prison. Her poem is phonetically spelled to show her speech patterns. “Voices Through the Walls” is a free-form collage poem which moves backwards and forwards across the page, giving each written phrase the sense of utterances from another cell or of graffiti on the walls. This poem is picked up at different times within the book.

Selina Salter’s story is disturbing. She’s described as a lunatic, but she seems sane, very angry, and possibly just rebellious and disobedient. She cries a lot and refuses to pick oakum because it’s so painful. They even try to deport her, but she comes back, and ends her days strapped to a bed. Her poem is in couplets and includes rhymes and repetitions. “The Order of the Administration of The Lord’s Supper and Holy Communion” is in the shape of a chalice. Scott’s use of all these different forms gives the collection variety, but also a sense of the many different women imprisoned here, often for crimes related to poverty. Scott’s range and skill allows this technique success.

The women activists aiming to win the vote, both Suffragettes and Suffragists, were famously imprisoned here, many force-fed in response to their hunger strikes. Sylvia Pankhurst’s poem uses the metaphor of cat and mouse, to describe how the law makes her feel, a mouse in their cat’s game of hunt, but she defies that notion:

Do mice fight for the

rights of their fellow

mouse? Do they want

equality for all breeds:

harvest, field, wood

house? Would they

give up food, water

sleep, for their cause?

Scott shows through this metaphor that Suffrage for women transcended class, that the sisterhood was not a snobbish one. The movement united women of all classes. It also demonstrates the women’s pride and commitment to their cause, as the argument is reversed to show it is the state that is the mouse, living in fear of the changes that may come when women take their part in government. The short lines and preponderant rhetorical questions strengthen the argument of the poem, in which only Pankhurst has a voice, as she rails against injustice.

Another prisoner, Katie Gliddon, takes refuge in Shelley’s poems. Allowed no seditious reading matter, she fools them by choosing poetry, which gives her strength: ‘I yell his sonnets from my window;’ but she also uses the book to write and sketch in, having smuggled in some pencils in her coat collar. And it’s not just the women Scott lends a voice to: Fred Pethick-Lawrence, who fully supported his wife, Emmeline, received the same 9 months sentence, though in a men’s prison, Brixton, where he was force-fed twice a day for ten days in his 9 month stretch. He thinks of his wife and imagines her lying drawn and pale on a ‘corpse bed’. Unlike the women, he can’t express his emotions and must show a stiff upper lip. Scott gives us an insight into both people in this poem, and makes the reader hope they were eventually reunited.

Scott’s willingness to experiment is demonstrated in a found poem, an anonymous letter to Emily Wilding Davison, while she was in a coma after being trampled by the King’s horse at the Epsom Derby in 1913. The typography has been carefully chosen so it can be read two ways, – i.e. an equivoque. The original hopes Emily will die in torture or be put into an asylum, but the words picked out in larger font show a counter-message crafted by Scott, which reads: ‘I am glad you are in hope. You are a person worthy of existence. Why don’t people find you?’ Davison would never have seen the letter, because she died of her injuries and failed to regain consciousness. Scott, in creating this poem from it, points to the horror of someone wishing this woman torment and death, after all she had already endured for the cause.

Scott does not shy away from writing about executions that happened in Holloway. There are a few poems which offer insight into the sentencing and treatment of Ruth Ellis, the last woman to be hanged in Britain. The famous executioner, Pierrepoint, is portrayed as seeing his role as a career choice (from limited options, admittedly) and in the end he decides to give up the profession after hanging Ellis in 1955, because ‘executions solve nothing’. There is also a poem in the voice of his wife, who detaches herself from his job and thinks about how his wages pay the bills. Scott includes details like the ledger he kept of those he’d hanged, and the way he’s always hungry when he comes home, as though the work had opened up a void in him. The poem in the voice of a juror is a powerful way to show Ellis’ desperation, and how she was judged for her lifestyle and appearance, though the fact she’d shot an abusive lover was never taken into account.

Is she guilty

of being a nightclub hostess,

an adulteress,

three men on the go at once,

divorced, bottle-blonde,

promiscuous.

(‘Juror’)

The poem in the voice of the officer who looked after her in the condemned cell, “Officer Evelyn Galilee”, compares Ellis to a broken doll, and sets up a counter-narrative to the way she was seen in court: ‘she was anything but /the hysterical moll / they’d painted her as’. “Ruth Ellis” is the final poem in this sequence, and movingly, Scott adds elements of the wedding ceremony, as though Ellis could see the love she desperately longed to have, and withheld by all her partners, in the eyes of the man who was hanging her:

The noose was poised

like a priest between us.

Do you take this woman?

Wisely, Scott does not end the collection with Ellis, but continues with a last iteration of the “Voices through the Walls”, and a handful more poems about different aspects in different styles, in line with the rest of the book. The final voice is ‘Sir Robert Carden’, a lord mayor of London from 1857-8, and magistrate. This poem rhymes abba, to underscore the ease with which Carden condemns women, showing no regard for their circumstances. The first stanza, repeated as the last, sounds like a death knell, with its flat masculine rhymes and long mournful vowels:

Smoke, mirrors, open the trap door

It doesn’t matter what you’ve done

If you’re guilty, your time has come

Hell always has room for one more

This is an astonishing collection, compelling and well-crafted. Scott’s poems are scalpel-sharp in exposing the suffering of the prisoners and the shocking inequalities of life for them, where well-fed men stand in judgement without the least understanding of why the crimes were committed: poverty, prostitution, ill-treatment including violence, and a burning desire for equality are common threads in the stories of the inmates of Holloway. This book would make an incredible stage show, to bring it to an even wider audience.

If you only read one poetry book this year, make it this one. You will be glad you did.

Angela Topping

Aug 24 2020

London Grip Poetry Review – Natalie Scott

Poetry Review – RARE BIRDS: Angela Topping is moved and impressed by Natalie Scott’s poems about a women’s prison

The book opens with a really helpful and concise history of Holloway prison, and there are some well-chosen epigraphs, which set the tone for Scott’s exploration of the prisoners, their crimes and their feelings about the place. The cover is stunning: a monochrome vista of London, with a sky full of empty birdcages already speaks volumes about the inmates and their stories. Added to this, the prison’s strange foundation-stone message of preserving the city of ‘evil doers’ is cleverly undercut by emboldening some of the prisoners’ letters to present the idea of a counter narrative about privilege, as most of the inmates were there for crimes caused by poverty and desperation.

Not all the voices are of women. The first poem is chillingly an advert calling people to come and see the criminals as though they were fairground exhibits. It is spoken by Major Arthur Griffiths, inspector of prisons from 1878-1896. The poem uses a fairly tight form to express his glibness. His shaming of the prisoners makes uncomfortable reading:

The list of different sorts of sinners is strongly reminiscent of the porter’s list in Macbeth, and thus, by association, summons up the rottenness at the heart of London at that time, which encouraged the ridiculing its criminals, often only guilty of petty crimes. There is also a quite astonishing othering of ‘foreigners’. The fact that these prisoners were made to parade past more fortunate people for the purpose of humiliation is shocking. It’s a very clever way to open the book, because the reader is now firmly on the side of the inmates.

After these opening salvos, the bulk of the work is where Scott takes different women’s voices to explore their histories. She gives their names and their crimes. The research is very impressive, but even more so is what she does with her knowledge. The range of forms allows each woman to speak her own story, with the poet an invisible shaping hand behind the scenes. The narratives that emerge are compelling.

Emma Mary Bird, found guilty of assault in 1852, is represented by her description in the record books, with her imagined thoughts added by Scott, such as Sallow for her complexion, followed by the recollection ‘yesterday I only ate scraps’. 89 year old Lydia Clemens, sentenced to 7 days of hard labour for begging, hopes she’ll put on some weight in prison. Her poem is phonetically spelled to show her speech patterns. “Voices Through the Walls” is a free-form collage poem which moves backwards and forwards across the page, giving each written phrase the sense of utterances from another cell or of graffiti on the walls. This poem is picked up at different times within the book.

Selina Salter’s story is disturbing. She’s described as a lunatic, but she seems sane, very angry, and possibly just rebellious and disobedient. She cries a lot and refuses to pick oakum because it’s so painful. They even try to deport her, but she comes back, and ends her days strapped to a bed. Her poem is in couplets and includes rhymes and repetitions. “The Order of the Administration of The Lord’s Supper and Holy Communion” is in the shape of a chalice. Scott’s use of all these different forms gives the collection variety, but also a sense of the many different women imprisoned here, often for crimes related to poverty. Scott’s range and skill allows this technique success.

The women activists aiming to win the vote, both Suffragettes and Suffragists, were famously imprisoned here, many force-fed in response to their hunger strikes. Sylvia Pankhurst’s poem uses the metaphor of cat and mouse, to describe how the law makes her feel, a mouse in their cat’s game of hunt, but she defies that notion:

Scott shows through this metaphor that Suffrage for women transcended class, that the sisterhood was not a snobbish one. The movement united women of all classes. It also demonstrates the women’s pride and commitment to their cause, as the argument is reversed to show it is the state that is the mouse, living in fear of the changes that may come when women take their part in government. The short lines and preponderant rhetorical questions strengthen the argument of the poem, in which only Pankhurst has a voice, as she rails against injustice.

Another prisoner, Katie Gliddon, takes refuge in Shelley’s poems. Allowed no seditious reading matter, she fools them by choosing poetry, which gives her strength: ‘I yell his sonnets from my window;’ but she also uses the book to write and sketch in, having smuggled in some pencils in her coat collar. And it’s not just the women Scott lends a voice to: Fred Pethick-Lawrence, who fully supported his wife, Emmeline, received the same 9 months sentence, though in a men’s prison, Brixton, where he was force-fed twice a day for ten days in his 9 month stretch. He thinks of his wife and imagines her lying drawn and pale on a ‘corpse bed’. Unlike the women, he can’t express his emotions and must show a stiff upper lip. Scott gives us an insight into both people in this poem, and makes the reader hope they were eventually reunited.

Scott’s willingness to experiment is demonstrated in a found poem, an anonymous letter to Emily Wilding Davison, while she was in a coma after being trampled by the King’s horse at the Epsom Derby in 1913. The typography has been carefully chosen so it can be read two ways, – i.e. an equivoque. The original hopes Emily will die in torture or be put into an asylum, but the words picked out in larger font show a counter-message crafted by Scott, which reads: ‘I am glad you are in hope. You are a person worthy of existence. Why don’t people find you?’ Davison would never have seen the letter, because she died of her injuries and failed to regain consciousness. Scott, in creating this poem from it, points to the horror of someone wishing this woman torment and death, after all she had already endured for the cause.

Scott does not shy away from writing about executions that happened in Holloway. There are a few poems which offer insight into the sentencing and treatment of Ruth Ellis, the last woman to be hanged in Britain. The famous executioner, Pierrepoint, is portrayed as seeing his role as a career choice (from limited options, admittedly) and in the end he decides to give up the profession after hanging Ellis in 1955, because ‘executions solve nothing’. There is also a poem in the voice of his wife, who detaches herself from his job and thinks about how his wages pay the bills. Scott includes details like the ledger he kept of those he’d hanged, and the way he’s always hungry when he comes home, as though the work had opened up a void in him. The poem in the voice of a juror is a powerful way to show Ellis’ desperation, and how she was judged for her lifestyle and appearance, though the fact she’d shot an abusive lover was never taken into account.

The poem in the voice of the officer who looked after her in the condemned cell, “Officer Evelyn Galilee”, compares Ellis to a broken doll, and sets up a counter-narrative to the way she was seen in court: ‘she was anything but /the hysterical moll / they’d painted her as’. “Ruth Ellis” is the final poem in this sequence, and movingly, Scott adds elements of the wedding ceremony, as though Ellis could see the love she desperately longed to have, and withheld by all her partners, in the eyes of the man who was hanging her:

The noose was poised like a priest between us. Do you take this woman?Wisely, Scott does not end the collection with Ellis, but continues with a last iteration of the “Voices through the Walls”, and a handful more poems about different aspects in different styles, in line with the rest of the book. The final voice is ‘Sir Robert Carden’, a lord mayor of London from 1857-8, and magistrate. This poem rhymes abba, to underscore the ease with which Carden condemns women, showing no regard for their circumstances. The first stanza, repeated as the last, sounds like a death knell, with its flat masculine rhymes and long mournful vowels:

This is an astonishing collection, compelling and well-crafted. Scott’s poems are scalpel-sharp in exposing the suffering of the prisoners and the shocking inequalities of life for them, where well-fed men stand in judgement without the least understanding of why the crimes were committed: poverty, prostitution, ill-treatment including violence, and a burning desire for equality are common threads in the stories of the inmates of Holloway. This book would make an incredible stage show, to bring it to an even wider audience.

If you only read one poetry book this year, make it this one. You will be glad you did.

Angela Topping