Poetry Review – SLEEPER: James Roderick Burns finds that Jo Colley’s new collection is very appropriate for the current difficult times

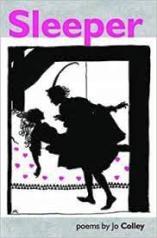

Sleeper

Jo Colley

Smokestack Books, 2020

ISBN 978-1-9161392-1-3

£7.99

Sleeper

Jo Colley

Smokestack Books, 2020

ISBN 978-1-9161392-1-3

£7.99

Sleeper is an extraordinarily timely collection. While many of us have struggled to find any positive aspect to COVID-19 and the lockdown period – especially where people’s health and livelihoods are threatened, and conversely, where keeping the country running has for some meant enduring a period of brutal, unrelenting work – Jo Colley offers (to echo Larkin) an enormous yes. It is not unalloyed positivity; the book is shot through with themes of darkness, despair, betrayal and worse, but overall Sleeper affirms what it means to be human in the most trying of times.

The collection is split into five sections, and moves through them on two arcs: from the clearest, most literal sense of sleepers (agents planted deep and working their way over decades into the target culture in order to achieve trust and access to secrets) – this includes telling poems on the Cambridge ‘Apostles’, and ‘The Wives of Kim Philby’ – through related, but more glancing senses (‘Cold War’) and finally to abstract notions of sleep, comfort and belonging itself, by way of women’s ambiguous role in all of these.

In parallel, as we move from Le Carré to motherhood (if not quite apple pie), the language moves from that of the taut thriller and the bureaucratic case report, often in terse prose poems, to more expansive ‘poetic’ verse. For instance, the opening poem, ‘The Ruling Class’, is short, brutally well-chosen and telling, a list with uncanny relevance to current leaders:

Nanny. Turtle soup. Nursery. Drawing Room. Estate. Boarder. Cloisters. Dormitory.

Michaelmas Term. Arcane uniform. Voice, and mouth. Bones. Willed blindness.

Selective deafness. Around them, servants they have turned into statues

It is easy to see how such people are prepared “for a life defended against compassion” (‘Barbarians’), and Colley’s controlled rage is evident on almost every page, as here in ‘Top Drawer’:

You are schoolboys regressing into booze, fuelled by boy’s own adventures and even

though you scatter wives and children along the way, still you are not men, even

though you send other men to their deaths, still you are not men, even though you

do your best for Comrade Stalin, still you are not men

The early poems rip and fizz with restrained passion. As the volume progresses, the title poem of the third section moves to a different tone – harsher, yet less explicit, almost plangent in tracking the long, grey social decline of the sleeper:

all conversations occur

in code

are heavy with irony

are lipread

eyebrows are raised

tremors and tics

are expected

if not required

people disappear

reappear

in different raincoats

with different codenames

the rubble

beneath your feet

is never ever still

(‘The Cold War’)

Similarly, as the startling, staccato prose poems fade out, longer, more meditative pieces begin to appear, and we move along another part of the arc. Colley retains her clear-eyed assessment of the world (indeed, the middle section could stand in for the overall theme of the book):

it’s not like I don’t understand

all the ways in which despair

can close a careful hand around the heart

How beautiful this is; how relevant, how measured (and still bleak). Yet in the same piece, the poet rises from this knowledge to a greater feeling, glorious and specific, gathered from simple observation and counteracting the grim diagnosis of the title:

but how I love the world: the bruised clouds

trees embrace their nakedness

crows stark against a pearl sky

(‘Cherophobia: an Autumn Journal’)

Nor does the poet restrict herself to her self – as the arcs of the collection move, upwards and outwards, she explores the layers of life and society that settle over people, and particularly women: sometimes they are cosy, almost welcoming, a blanket of retreat from the world into the comfort of memory:

After the rituals of pills,

eyedrops and tea, she made herself a nest,

became her own chick, a hatchling barely dry,

awaiting the arrival of her mother, whose

devoted beak dripped tenderness

(‘Comforter’)

At other times, they become both sinister and absurdly funny:

The apron

wrapped itself around her waist, tightened,

tightened. Until the prick of revelation found

its way under her fingernail, released her

from the spell: of love, of duty, who can tell?

She cut her way out with the kitchen knife,

abseiled down the ivy in her underwear

(‘Sleeping Beauty’)

But it is in the seemingly-lighthearted sequence of vignettes about her mother, neatly distilling in verse the sort of controlled bursts of emotion she packed into prose poems at the beginning, that Colley underlines how we must find the positive in a world that will overwhelm us if we let it; subvert what we are given to make over the grey, and the misery, into light for the future. ‘My Mother as … a Music-Hall Favourite’ gives way to ‘Captain of a Grimsby Trawler’, ‘Member of the Royal Horticultural Society’ and ‘Best-Selling Lady Author’, but it is in ‘My Mother as Cat Woman, the Undetected Jewel Thief’ that we feel all of the currents of the book swell into its great conclusion, which needs no explanation, and is reproduced here in full:

Unlikely as it seemed from her small stature

and the curvy hips, she was an expert inserter:

like a shape-shifting slug, she found her way

into the smallest crack, slid through the keyhole

and under doors into intimate space. There

she lifted what she could, her hands deft in

elbow length kid gloves, her diamond bright

stash slung over her perfect shoulder. No one

except me ever put her in the frame. After she died,

I encountered the gloves down the side of the sofa,

a madeleine of memory, a Proustian punch in the gut.

.

James Roderick Burns

Jul 6 2020

London Grip Poetry Review – Jo Colley

Poetry Review – SLEEPER: James Roderick Burns finds that Jo Colley’s new collection is very appropriate for the current difficult times

Sleeper is an extraordinarily timely collection. While many of us have struggled to find any positive aspect to COVID-19 and the lockdown period – especially where people’s health and livelihoods are threatened, and conversely, where keeping the country running has for some meant enduring a period of brutal, unrelenting work – Jo Colley offers (to echo Larkin) an enormous yes. It is not unalloyed positivity; the book is shot through with themes of darkness, despair, betrayal and worse, but overall Sleeper affirms what it means to be human in the most trying of times.

The collection is split into five sections, and moves through them on two arcs: from the clearest, most literal sense of sleepers (agents planted deep and working their way over decades into the target culture in order to achieve trust and access to secrets) – this includes telling poems on the Cambridge ‘Apostles’, and ‘The Wives of Kim Philby’ – through related, but more glancing senses (‘Cold War’) and finally to abstract notions of sleep, comfort and belonging itself, by way of women’s ambiguous role in all of these.

In parallel, as we move from Le Carré to motherhood (if not quite apple pie), the language moves from that of the taut thriller and the bureaucratic case report, often in terse prose poems, to more expansive ‘poetic’ verse. For instance, the opening poem, ‘The Ruling Class’, is short, brutally well-chosen and telling, a list with uncanny relevance to current leaders:

Selective deafness. Around them, servants they have turned into statuesIt is easy to see how such people are prepared “for a life defended against compassion” (‘Barbarians’), and Colley’s controlled rage is evident on almost every page, as here in ‘Top Drawer’:

The early poems rip and fizz with restrained passion. As the volume progresses, the title poem of the third section moves to a different tone – harsher, yet less explicit, almost plangent in tracking the long, grey social decline of the sleeper:

all conversations occur in code are heavy with irony are lipread eyebrows are raised tremors and tics are expected if not required people disappear reappear in different raincoats with different codenames the rubble beneath your feet is never ever still (‘The Cold War’)Similarly, as the startling, staccato prose poems fade out, longer, more meditative pieces begin to appear, and we move along another part of the arc. Colley retains her clear-eyed assessment of the world (indeed, the middle section could stand in for the overall theme of the book):

it’s not like I don’t understand all the ways in which despair can close a careful hand around the heartHow beautiful this is; how relevant, how measured (and still bleak). Yet in the same piece, the poet rises from this knowledge to a greater feeling, glorious and specific, gathered from simple observation and counteracting the grim diagnosis of the title:

but how I love the world: the bruised clouds trees embrace their nakedness crows stark against a pearl sky (‘Cherophobia: an Autumn Journal’)Nor does the poet restrict herself to her self – as the arcs of the collection move, upwards and outwards, she explores the layers of life and society that settle over people, and particularly women: sometimes they are cosy, almost welcoming, a blanket of retreat from the world into the comfort of memory:

After the rituals of pills, eyedrops and tea, she made herself a nest, became her own chick, a hatchling barely dry, awaiting the arrival of her mother, whose devoted beak dripped tenderness (‘Comforter’)At other times, they become both sinister and absurdly funny:

The apron wrapped itself around her waist, tightened, tightened. Until the prick of revelation found its way under her fingernail, released her from the spell: of love, of duty, who can tell? She cut her way out with the kitchen knife, abseiled down the ivy in her underwear (‘Sleeping Beauty’)But it is in the seemingly-lighthearted sequence of vignettes about her mother, neatly distilling in verse the sort of controlled bursts of emotion she packed into prose poems at the beginning, that Colley underlines how we must find the positive in a world that will overwhelm us if we let it; subvert what we are given to make over the grey, and the misery, into light for the future. ‘My Mother as … a Music-Hall Favourite’ gives way to ‘Captain of a Grimsby Trawler’, ‘Member of the Royal Horticultural Society’ and ‘Best-Selling Lady Author’, but it is in ‘My Mother as Cat Woman, the Undetected Jewel Thief’ that we feel all of the currents of the book swell into its great conclusion, which needs no explanation, and is reproduced here in full: