Poetry Review – John Dust: Adele Ward finds enjoyable surprises in Louise Warren’s new pamphlet

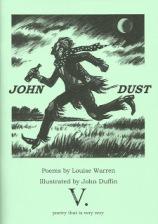

John Dust

Louise Warren (Illustrated by John Duffin)

V. Press

ISBN 978-1916505285

36 pp £6.50

John Dust

Louise Warren (Illustrated by John Duffin)

V. Press

ISBN 978-1916505285

36 pp £6.50

The wiry figure of John Dust leaps into Louise Warren’s pamphlet and runs through it in ragged clothes. He appeals to us like a familiar character from dark childhood fairytales and pagan legends, and yet he’s an invention. His name makes us think of mortality, but the imagery around him is fertile with life: the cycle of birth, death and rebirth.

His omnipresence gives a unique flavour to this short collection, but there’s far more here, with poems set in Warren’s Somerset locality that are resonant with the atmosphere of magic realism. We’re on Angela Carter territory and we are drawn in, waiting for each surprise as nature is described in striking and unexpected ways.

There are no weak poems and the intense atmosphere is maintained throughout. Take a look at some excerpts from two of my favourites, ‘Cuckoo’ and ‘Owl Strike’. ‘Cuckoo’ describes the mechanical inhabitant of a clock, with the careful observation of its owner demonstrating an attention to detail that suggests solitude:

Behind the door, he hangs his tongue on a nail

but I can hear the whirring of trapped wings.

In that space between one minute and the next

my impostor waits, in the scratchy dark.

Such care has gone into the writing of each line, the choice of wording and metaphor, and this is typical of the whole pamphlet.

In ‘Owl Strike’ we read about an experience that will be familiar to everyone – a bird flying into a window. But Warren takes this to a higher level with the quality of her language:

That night the owl printed a ghost of an owl

as it slammed into the window

the moon held its breath

and again we hear the isolation and vulnerability of the speaker suggested:

He spied my small bones wrapped up in the bedroom dark

but the window stopped him –

he spilt his white heat onto the glass

the night rushed in…

Even a seemingly trivial subject can take on magnitude when seen through Warren’s keenly observant eye and original viewpoint. In ‘Fly’ she is writing in the tradition of poets like D.H. Lawrence, who excelled in poetry about creatures from mosquitoes to elephants:

How beautiful he is in death

laid out in the white afterlife

like a god, a fly on the sill

in a tapestry of cup rings.

I have picked out these poems as examples of the striking nature and observational poems which go along with the ones on the theme of legend which hold the collection together. John Dust wanders the countryside or interacts with the poet, lingering near, or even communicating with her on a visit to the Museum of Somerset where the skeleton of a woman with a small dog from 300-400 AD is exhibited.

Some poems capture the Somerset countryside, with ‘The Drowned Field’ and ‘The Marshes’ showing a far from picturesque rural scenario, while the interior of the home is also described in unexpected ways:

Downstairs, the afternoon moves heavily around the house,

a washing line turns slowly on its stalk,

the carpet in the hallway runs a sluggish ditch.

(‘The Marshes’)

Indoors and outdoors are merged in the imagery of this poem and also in the relationship the narrator has with John Dust:

Deep inside the bathroom I undress myself for you,

John Dust.

Down to the sedge and water, down to the beak of me

sharp in the reed bed, down to the hidden.

Similarly, in ‘Winter Bathroom’, we read that ‘Out of the tap runs a long cold evening, the colour of lead,/of November between the hours of four and six’. I know that feeling.

The pamphlet opens with ‘John Dust’, a poem describing him in short lines, like an adult nursery rhyme. In fact we’re told that he has a ‘face full of cows like a nursery rhyme’, a ‘face full of buttercups, open’ and a ‘face like a field turned over’. John Dust is associated with beautiful natural imagery and with the soil that suggests mortality. But he also has a ‘coat stuffed with apples’, overflowing with fertility and harvest.

The nursery rhyme atmosphere of this poem and several others is matched by a set of riddle poems near the end, which cryptically challenge the reader to decipher clues relating to the previous poems, sending us back through the pamphlet.

I left a sequence of five short prose pieces called ‘The Parish Magazine’ until last, not realising what a joy they are in their surreal take on superficially ordinary events, such as cricket matches and the local Neighbourhood Watch. There is nothing predictable with Warren.

John Dust is illustrated by the award-winning painter and print-maker John Duffin, adding to the folktale feel of the pamphlet and letting us see Warren’s legendary figure.

May 29 2020

London Grip Poetry Review – Louise Warren

Poetry Review – John Dust: Adele Ward finds enjoyable surprises in Louise Warren’s new pamphlet

The wiry figure of John Dust leaps into Louise Warren’s pamphlet and runs through it in ragged clothes. He appeals to us like a familiar character from dark childhood fairytales and pagan legends, and yet he’s an invention. His name makes us think of mortality, but the imagery around him is fertile with life: the cycle of birth, death and rebirth.

His omnipresence gives a unique flavour to this short collection, but there’s far more here, with poems set in Warren’s Somerset locality that are resonant with the atmosphere of magic realism. We’re on Angela Carter territory and we are drawn in, waiting for each surprise as nature is described in striking and unexpected ways.

There are no weak poems and the intense atmosphere is maintained throughout. Take a look at some excerpts from two of my favourites, ‘Cuckoo’ and ‘Owl Strike’. ‘Cuckoo’ describes the mechanical inhabitant of a clock, with the careful observation of its owner demonstrating an attention to detail that suggests solitude:

Such care has gone into the writing of each line, the choice of wording and metaphor, and this is typical of the whole pamphlet.

In ‘Owl Strike’ we read about an experience that will be familiar to everyone – a bird flying into a window. But Warren takes this to a higher level with the quality of her language:

and again we hear the isolation and vulnerability of the speaker suggested:

Even a seemingly trivial subject can take on magnitude when seen through Warren’s keenly observant eye and original viewpoint. In ‘Fly’ she is writing in the tradition of poets like D.H. Lawrence, who excelled in poetry about creatures from mosquitoes to elephants:

I have picked out these poems as examples of the striking nature and observational poems which go along with the ones on the theme of legend which hold the collection together. John Dust wanders the countryside or interacts with the poet, lingering near, or even communicating with her on a visit to the Museum of Somerset where the skeleton of a woman with a small dog from 300-400 AD is exhibited.

Some poems capture the Somerset countryside, with ‘The Drowned Field’ and ‘The Marshes’ showing a far from picturesque rural scenario, while the interior of the home is also described in unexpected ways:

Indoors and outdoors are merged in the imagery of this poem and also in the relationship the narrator has with John Dust:

Similarly, in ‘Winter Bathroom’, we read that ‘Out of the tap runs a long cold evening, the colour of lead,/of November between the hours of four and six’. I know that feeling.

The pamphlet opens with ‘John Dust’, a poem describing him in short lines, like an adult nursery rhyme. In fact we’re told that he has a ‘face full of cows like a nursery rhyme’, a ‘face full of buttercups, open’ and a ‘face like a field turned over’. John Dust is associated with beautiful natural imagery and with the soil that suggests mortality. But he also has a ‘coat stuffed with apples’, overflowing with fertility and harvest.

The nursery rhyme atmosphere of this poem and several others is matched by a set of riddle poems near the end, which cryptically challenge the reader to decipher clues relating to the previous poems, sending us back through the pamphlet.

I left a sequence of five short prose pieces called ‘The Parish Magazine’ until last, not realising what a joy they are in their surreal take on superficially ordinary events, such as cricket matches and the local Neighbourhood Watch. There is nothing predictable with Warren.

John Dust is illustrated by the award-winning painter and print-maker John Duffin, adding to the folktale feel of the pamphlet and letting us see Warren’s legendary figure.