May 30 2020

London Grip New Poetry – Summer 2020

The Summer 2020 issue of London Grip New Poetry features:

* Margaret Hollingsworth * William Bedford * Carl Griffin * Tim Youngs * Belinda Rimmer

* Raymond Miller * Richie McCaffery * Hannah Hodgson * Bruce Christianson

* James Fountain * Stuart Handysides * Stuart Pickford * Barry Smith * Jane Simpson

* Tim Miller * Chris Armstrong * Tim Cunningham * Stephen Bone * Kate Noakes

* Tess Jolly * Marie Dullaghan * David Flynn * John Short * Gareth Culshaw

* Ava Patel * Phil Wood * Sonia Jarema * Stella Wulff * Pam Job

* John Freeman * Teoti Jardine * Selese Roche * Keith Nunes

* Hayden Hyams *Neil Richards

Copyright of all poems remains with the contributors. Biographical notes on contributors can be found here

London Grip New Poetry appears early in March, June, September & December

A printer-friendly version of this issue can be found at

LG New Poetry Summer 2020

SUBMISSIONS: please send up to THREE poems plus a brief bio to poetry@londongrip.co.uk

Poems should be in a SINGLE Word attachment or else included in the message body

Our submission windows are: December-January, March-April, June-July & September-October

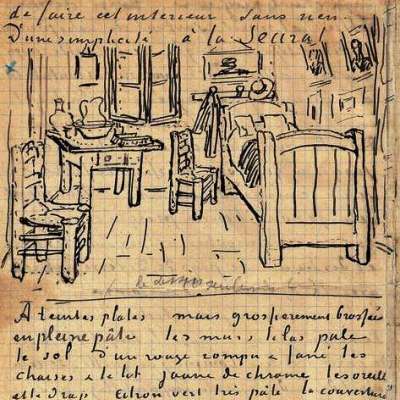

Our header illustration comes from a letter written by Vincent Van Gogh to his brother Theo and is appropriate for two reasons. Firstly, it illustrates a poem by Neil Richards which appears at the end of this issue; but secondly the delightful compact sketch of Vincent’s narrow and cluttered room surely captures the conditions under which many of us have been living as we isolate ourselves in order to combat the threat of coronavirus.

Naturally there are references to Covid-19 in the poems which follow. These are mostly personal responses, reflecting on mortality or lamenting loss of human contact. But we have not let these themes dominate the issue, believing that a more varied and panoramic view would be welcome to readers living restricted lives in a time of uncertainty and anxiety. We hope that you will agree that, broadly speaking, we have provided some diversion and perhaps a little encouragement.

Michael Bartholomew-Biggs

London Grip poetry editor

Forward to first poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Margaret Hollingsworth: Iridescence

He doesn’t talk much, really talk I mean,

he's a bird man, just a hobby, says he loves starlings,

the lure of the ordinary ruined by explanation

the iridescent feather colours are produced

by nanoscale arrays of melanin

they contain organelles, (melanosomes).

His love of full disclosure doesn’t extend to hair loss,

he always wears a hat. He has snapbacks, strapbacks,

flexfits all colours, he has trilbys, fedoras, hombergs,

beanies, berets. Ball-caps I hate, measure your dome,

6 cloth triangles and a fabric covered squachee,

Baldness is caused by an excess of hormones on the scalp.

I brush flakes of dandruff from his shoulders every day

he went bald the year we got engaged,

implies the efflorescence is my fault.

He holds his fork like a lacrosse stick. I tell him in England lacrosse

is a girls’ game, though it was invented by the Iroquois (for men).

He reminds me gender's no longer relevant, tells me

iridescence is the result of interference between reflections

on butterflies and birds' wings, this interference

is created by a range of phototonic mechanisms,

chews his chop too long. I ask him, is it tough? He tells me

some cuts of meat show structural colouration, ditto soap bubbles.

Like the sheen on glazed cotton sheets or on his tongue?

We used to share a bath till the bath was too tall

for us to clamber in. I still wash his back

the most intense iridescent blue known to man is the Marble Berry,

not African of course, quite pretty though, quite like your eyes

pretty. I never accompany him to conferences

though I pack his bird books. I pack his hats.

When he got back from Chad the starlings

were still with us, still iridescent. Now they’ve taken off

beaten back by ravens. He died of tetanus.

I must admit I mind the starlings' absence, crave their squabbles,

their selfishness, their sheen. It took two journeys

to the Thrift Store to dispose of all his hats.

That Sunday a bat swam in the coffee urn, wings spread,

cold coffee's iridescent sheen bathing its pate. Bat rescuers,

it doesn't take a genius to guess which one of us it bit.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

William Bedford: Cinéma Vérité I thought it was the heat, but the skin has been scraped off the back of my throat and the sweat saturates my clothes. I sit in a cinema and drench the seat. The usherettes whisper and shine their torches. My illness embarrasses them, more than the lovers on the screen. I tell them, ‘This asthma of love is a choking cholera.’ A nurse in a cocktail dress offers to change the reels. ‘Are you enjoying the film?’ she asks politely. A large giraffe ambles into the cinema, and demands a free ticket for its part in the film. I lie between the aisles and the usherettes prepare my stretcher. In the dustbins I might find food. There will be lovers making noises while I am eating. They will not put me off my meal. I did not enjoy the film. William Bedford: Walking in the Sea This hot August sunlight is not the weather for walking in the sea, but we walk in the sea, our feet up to our ankles in cold water, our toes punishing the ribbed sands which are like a pullover God forgot to take off. A plover follows us, warbling its curiosity. When I was a child, growing up beside the sea, these sands would be brilliant with deckchairs, their rainbow stripes and plaguey impetigo dotting the shores like patients waiting for the doctor. The sky is steely blue today, but there are no deckchairs, because all the tourists have left for Barcelona, like lemmings in a fine frenzy, wooden horses floating out to sea. I do not know why I said this is not the weather for walking in the sea, when it is clearly the perfect weather for walking in the sea, even the plover is reluctant to leave the tideline. Our toes continue to punish the ribbed sands, but we walk several inches apart, keeping our distance, like God in her unravelling workshop, searching for the pullover she forgot to take off.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Carl Griffin: Diagnosis The chair’s like a floating jetty, it teeters – dependent on your first word. Dr. Cresey-Rogers can direct you back to safety or tip you over the embankment. Do you smell things that others cannot smell? he asks me. And through suggestion, I get a scent of salt water on his trousers: rock pools, gobies. Can you see things other people can’t quite discern? The chair extends into a harbour without a guide – except Dr. Crazy- Rogers, who recommends assessment at a psychiatric vessel on the distant water.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Tim Youngs: Stone The guide to fossils, rocks and minerals told me it was jade I dug up between the radishes, carrots and runner beans I’d grown to sell for a few spare pennies. It’s a piece of flint! My parents’ mocking. Well, I’d tell my child: Let’s try some knapping.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Belinda Rimmer: Uprooted She unearths a farthing date worn smooth, 1936. She thinks of her grandfather, trousers held up by string, holes in his boots, cracked hands gracefully tending brick. From his pocket the farthing tumbles, ricochets off his spade, buries itself. She thinks of all things lost and found.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Raymond Miller: Inclusion As we pull into the car park of St Margaret’s church, they come dribbling along like a defeated army: the disabled, the autistic, those who simply find learning difficult, those who make us uneasy. Most have walked the ten minutes from school to church, others have been pushed, or carried, and the big blonde boy whom I recall from Sports Day, with the face of an angel and the physique of a god, requires two adults to guide him in the desired direction. I don’t think it’s because he’s aggressive, only possessed of a nagging desire to be somewhere other than where he is. My wife returns to the car for a pack of tissues and when we enter the church, Sheila hands us a programme. She is Sheila, and not Mrs Lines, because all the teachers and children are on first name terms. The programme appears skilfully designed to produce the tears those tissues are intended to absorb - stick-like drawings, poorly spelt prayers and grammatically exotic expressions of gratitude. The headmaster calls himself Ed the Head. He addresses the assembled and the hubbub subsides, apart from what sounds like an aeroplane humming, but which I’m informed is a boy called Robin and this is the noise Robin makes all day long. Ed the Head reads the names of the year 6 leavers, all 23 receiving a round of applause and I whisper to my wife that he sounds like Mr Tumble, the lovable children’s entertainer. He does! she laughs, they must come from the same area. Or, it occurs to me that special school staff might need to pretend they are someone else to get through each day and Mr Tumble is an astute choice. Sat next to me is a child in a wheelchair, whose name is Mohammed, who is silent and immobile despite the best efforts of his Teaching Assistant, who’s been speaking and signing to Mohammed throughout. A group of children sing My Love is like a Mountain, and she takes his hands, swinging and clapping, but Mohammed remains unmoved. He is unmoved even by a rousing rendition of My School is a Good School which has most of the children and teachers bouncing around in their chairs. Then all the year 6 leavers sing Lean on Me, the old Bill Withers number. They are remarkably harmonious, and make a decent stab at leaning on each other in unison, all except for Thomas, who stands apart from the rest, spinning circles like Bez from the Happy Mondays. I ask my wife if she thinks this has been choreographed, but she’s buried herself face-deep in tissues. The song ends. Robin’s humming aeroplane re-enters the atmosphere, punctuated by sniffles, the phut-phut of failing engines. We find our daughter, her face contorted by tears, her autographed school top a tattoo of love. One of her classmates hugs her, we hug her. I cannot speak. I cannot speak for fear that I too might break down or break up and cease pretending to be someone else to get me through the days. As we are leaving I notice the blonde boy still endeavouring to escape his handlers. In the car I ask my daughter where she thinks he is trying to get to. The dining room, she replies, very matter-of-fact, and I burst into laughter and tears. Just like a god has come down to earth.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Richie McCaffery: Vocabulary You need to go back to primary school when we were given names for things like colours and they were faded in the process. We were given a name to answer to, one per person and you were told to just be yourself. But that was only so no-one else had to. School reports always said you showed promise and like all promises you never kept it. I still write in old notebooks stolen from school years ago. The only difference is a bit of fading, the staples gone rusty and the writing somehow more legible but making less sense. Richie McCaffery: Certificates . i. I found my birth certificate – the original in ersatz parchment – quite by accident, stuffed into a half-read book, about to be sent to the charity shop. Who needed the proof I was real? I’ve forgotten now. The registrar’s writing is slanted as leaning into the future. The 190th birth in that hospital in 1986. My dad’s listed as a ‘Land Surveyor’ and my mother’s job’s not called for. . ii. When my Aunt Rita died we were the only family in the country so we got the task of clearing her house. We were going to bin the death certificate for her husband who’d succumbed to some polysyllabic disease in the 1970s. But I kept it, out of nagging fear I might have to deal with his ghost one night looking for proof he really was dead, as if there’s bureaucracy beyond too.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Hannah Hodgson: This is Moving On A decade on, we’re moving house and my dad has to confront the trauma in the loft. My Grandad’s belongings now slightly damp; Lead Soldiers await redeployment. Dad names every fireman on a photo taken outside Lancaster City Hall. Grandad was halfway up a ladder, with a professional smile. There are cap badges from the Special Forces and Fire Brigade, which Dad insists must go. He flicks through Grandad’s passport and paper driving licence; tries to pry free a photo that rips apart. Dad pretends this is fine, we all do – that the landing is a sensible place to sort the remains of a life. Dad goes out to the garage and smokes. Then, drives to the dump before getting sentimental.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Bruce Christianson: Application for Unsettled Status How long have you been living in this country? since 987 Give details of any absences from the UK since 1987. salem in 1691 oh since 1987 one coven in germany each spring How did you leave and re-enter the UK on these occasions? mostly i flew but once (the weather was awful) i took the eurostar & offset the carbon later Have you cohabited while in the UK and if so with whom? i share a bedroom with my younger self there was a handsome devil also for a while but he failed the cricket test (truth is i ran him out) Did you maintain a common household e.g. by sharing toiletries? he was a mathematician & created vast piles of paper that i’m still working through Are you actively seeking work? well as it so happens on second thought i’ll just say no to that According to our records you have indefinite leave to remain. indefinite is so unsettlingly precise

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

James Fountain: Trying to remember what it was like I sit quietly, in a half-trance, trying to remember you, separating pages of The Daily Telegraph with a breath, scrutinising every column as though it contained world-shaking information. Trying to remember the pub in West Hartlepool, where you used to plonk me and my sister, then disappear into the mysterious front room, leaving us to challenge regulars to dominos. Trying to remember your handshake, your calm look, then an angry one, later, when my mother mentioned money, when she criticised anything you felt was fine, as it was.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Stuart Handysides: Une petite histoire des boîtes d’allumettes avant le Brexit I strike the last Spanish match (fabricado en India) from the six boxes bought last year when I learnt to ask for fósforos de seguridad, or luciferos. Still proud my wish was understood that day when the rain in Spain was cold the tent was small, my back ached and the most important thing was making tea. Ce matin, il y a du brouillard, and the first Streichholz (made of aspen wood, in the EU) from a box found in a Black Forest supermarket will light the gas to perk my caffè Italiano. Back in Blighty boxes of England’s Glory display HMS Devastation (long-scrapped) over “Made in Sweden”.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Stuart Pickford: Space Race In a Moscow apartment for Soviet heroes, a cosmonaut’s wife lights the gas stove; the flame sucks at air as her husband’s face drifts across a hatch, pulled to the sun, again, to be burned up like a struck match. Stuart Pickford: Shingle Street You know it by shingle saying its name at the water’s edge, shingle sifted and graded and weighed all down the beach. You pick up a hag stone the sea has worried, poked its tongue through. You hold it to your eye, old Captain Stone Eye; me flitting across the aperture. A few shacks have hunkered down. Behind the net curtains, the dead; their places laid at the table. The sea claws at what it desires, spits at you. In the borstal, boys on garden duties hoe around lettuces which’ll never amount to much, stunted by the salt in the air. Sea spurrey and valerian show what’s possible.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Barry Smith: Deep Water A woman is weeping by the sea-shore as so many have done before she wants to go home she sobs and rocks the skin of her knees peering through the frayed denim of designer jeans a bearded man hefting a loaded backpack looks on, his face a mask, rigid, helpless he’s lost she’s far away weeping at the sea-shore we gather awkwardly offering help she clasps a woman’s hands locking onto human warmth she wants to go home but doesn’t seem to know anymore where home is or was I’ll be alright, she says I’ll be okay you’re so lovely, she says and weeps the bearded man is stiff he tries to touch her curling shoulder he asks for a light for his roll-up cigarette but we have no light to give and we cannot help him to reach her or her to get back home

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Jane Simpson: Without us Lake Victoria is my Brighton Beach, a place to escape within the sanctioned 2km radius of home. Little Hagley Park is my Pissarro; this autumn a boulevard of leaves clapping before dusk across distant balconies. The Botanical Gardens is an island in an island nation – with locked gates. Each day green comes closer to red. Do colours exist when no-one sees them. Jane Simpson: Ars poetica Lines break under my hand parse and enjamb make my eyes speed and slow a soundless track when traffic is quiet my neighbours asleep first draft fire in the mind pixels on a screen the freedom of not having to speak. Two zones please the bus driver reads my jotter pad and gestures back two empty seats one by the window the other for my pack all around me pixels glow noise-cancelling headphones blank out unwanted conversations with artificial intelligence. On Sunday I am safe in the austerity of Evensong with its few vocal parts The Book of Common Prayer Elizabethan cadences strip me bare.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Tim Miller: Caedmon Comes to Singing Caedmon was well on in years when he fell asleep in the stable and was told to sing. Syllables had never sounded from him before, and in the dim night he’d already abandoned dinner when he heard the harp being hauled out for the drunks to drool out their dumb songs. Natural beasts were better than those brutes: he came to immediate calm amid their massive warmth and like waves the voice arrived in a vision and a summons for sleeping Caedmon to sing, to make a canticle on nothing less than creation, to fill the firmament again with that first moment. This was Caedmon’s morning poem, more his midnight poem, the poem from which all others proceeded, syllables sprung from his sleep beside the animals.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Chris Armstrong: On Meeting a Poet I finally read your book today started, and couldn't stop. Yours are poems - beautiful - that stop and hold my brain poems that make me question if I have ever written poetry at all set me to question for a moment if the shapes of my verse weave poems out of my words, even, if my words craft my thoughts into poems but the moment passed as I felt your passion painted on the page and, I am content to know a poem is what leaves my heart and pen so at the end, quietly, perhaps we can silently smile at my angst

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Tim Cunningham: The Omega Prize To complement our successful Alpha Prize for First Collection, We are pleased to invite submissions For our inaugural Omega Prize Awarded for a last collection. To be eligible to enter You must have published At least one previous book of poetry And your entry must, absolutely, Be your last. ‘Last’, of course, Implies there was a first, And your submission cannot be considered For both first and last. A ‘Selected’ does not qualify. Entrants are advised that titles Like ‘Residues’, ‘Remainders’ or ‘Etcetera’ Send out the wrong message. We expect swan songs, Late flowerings of imagination and style. The rules are stringent. If your selection is adjudged the winner But you publish a later work, Your prize will be rescinded And appropriate action considered. If you pass away before the award is decided, Your entry will automatically be void. But if you should pass away After you are announced the winner, You will be pleased to know That the prize will be awarded posthumously. What a wonderful memento mori that would be For your family and friends. And if you are already the recipient Of the Alpha Prize, think What wonderful bookends to a life in poetry. Presentation of the award, followed by book launch, Will take place on 1st March In the crypt of St. David’s, Patron Saint of Poetry. We hope to see some of you there. Tim Cunningham: Omega Purchased for two weeks’ wages In the jeweled distance of 1969, I missed that clue in the name: ‘Omega’, a watch for life, Inseparable, joined at the wrist. At school, we sang from ‘My Grandfather’s Clock’: ‘And it stopped, short, Ne’er to go again When the old man died.’ The lyrics chimed this winter When the virus struck, Simultaneously inhibited the spring In my watch and step. Recovered now, I wait For news of the ‘Omega’, stretched On the purple, velvet bed Of horological’s intensive care. Meanwhile, the jeweller has lent me a ‘Lorus’. ‘On borrowed time’ springs to mind.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Stephen Bone: Final Descent For just shy of fifty, I manned the latticed gates, pulled the brass lever that started the soft judder of the cabin's ride. Learnt here to gauge atmosphere, when to offer a shoulder, a joke, keep it silent, official. Saw tenants come and go, grew to know their traits: the widow with her drum-tight face, minute, deadly dogs, the dentist on eleven, breathing mint and Wild Turkey, the Englishman with his out for a duck, silly mid-off, I'd take to the top floor, to view the Manhattan night, like a diver on the highboard, a witness said. Self push buttons did for me, sent me the way of telegram boys, usherettes selling smokes from strapped on trays. The uniform, my second skin, they let me keep. Hangs mothproofed, ready for my final descent.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Kate Noakes: Waiting for Ikebana, Mayfair Shop assistants at the perfumery - de père en fils depuis 1760 – are so bored they spend most of their time dousing themselves in precious and pricey scent. Well-heeled ladies take lifetimes choosing precipitous shoes. The footwear consultant on a fag break cradles a white china mug and totters the pavement in evening sandals. Every boutique has a security guard. Early November, and already Christmas decorations bling the street. The restaurant’s standard bay trees are baubled in tasteful oranges and pinks. Outdoor heaters release pyramids of fire. A preened young man shows off his grooming on video chat. Sunday morning, sunny, and I am about to do precise things with flowers. I know we are living in the end of days. Still, there is art.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Tess Jolly: Cherish When she introduces herself as Cherish and says she’ll be your assistant today she sounds so in love with the jaunty Ch carried effortlessly through passionate teeth-gnashing riches into the long fricative flow so close to cherub, cherry, treasure, the delicate sea-horse dancing on hush-now-shingle-shiver of water over stones, and you wonder if a lifetime repeating the mantra I’m Cherish, my name’s Cherish would help you to believe but probably knowing you your brain would get tired from making the effort, your neurons fail to see the point in continuing to fire and the word become strange, like that dream where your son appeared as Mr Potato Head at your bedside one morning all hopeful and brimming with trust, and you tenderly removed bowler hat and glasses then went too far as usual and unclipped the warm accessories of ears, nose, mouth, the darling plastic limbs.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Marie Dullaghan: Flawed He calls himself ‘Rabbit’, nibbles lettuce, watches her from under the table. She has been baking bread for days, or weeks, maybe. Tray after tray. The pickled oranges stare anxiously at the apple chutney. The loaves are every shade of brown from almost cream to almost black, but some are tasteless, too heavy, too much salt or sugar, too crusty. Among the cherries a solitary grape screams ‘green’ in the white fruit bowl. She frets. No one will love her imperfect bread. Better stick to scones. In its cardboard nest, one of her eggs is cracked.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

David Flynn: She wanted. She wanted. That’s a period. She wanted. Her whole heart reached out in the department store. Her whole heart. That’s a period. In her billfold were six credit cards, all maxed. In her billfold was an organ donor card. In her billfold was her driver’s license. The photo when she was a blonde— She was red-haired now. Then long now short. The photo when she wore that purple blouse. Too many holes after washing and she threw it in the garbage. In her billfold were two dollar bills. She wanted. Her heart reached out to a rack of pants. Her heart reached out to the shoe department. Her heart reached out to a bottle of perfume in the glass case. She wanted. But she left. Wanting is free, she thought. Buying costs. In her car, leased, two payments behind, threatened repossession already from the finance company. In her car she smiled. Take away my condo, take away my furniture, take away my pots and pans, my 36-inch Smart TV. Take away. I’m still cool. Can’t take away my cool. I can still strut. Can’t take away my strut. She wanted. And she was smarter than her wanting. Smart was good. Stupid was bad. She was smart. No money, but smart.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

John Short: Promise Barcelona She tells him how death secured a pension and a name, how she only now persists for pocket cash and camaraderie fixed by patterns of habit and scared of solitude so in this miserable room sprinkled with city dust they seal again their symbiosis. She brings in beer, then as the pulsing fan blows heat they clasp like beasts in season, surpass allotted time; meet next day for coffee in shadows of a sun-baked afternoon where last night’s perfume rises from ancient drains; realise this chemistry suggests another step beyond money and words that brim with promise.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Gareth Culshaw: Hold On A Moment Yesterday’s curry has spread itself on the rug. Our dog sniffs the air and mother snaps a tut in her mouth. Her cigarette smoke clouds the sky I know. She coughs into my eyes as I scrub. I tell her work is tomorrow, silence will come. The dog watches me he knows there’s threads of chicken on the floor. Mother changes the T.V channel her voice stays the same volume. Hammers words onto my spine until the weight arches my height. I tell her there’s a key in a bedsit from a friend. It may open a door for us both to leave this room behind.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Ava Patel: Foxing Fox tears every evening apart and chews up the night— it’s his dinner and he is starving. The small animals already lining his tummy quiver; their munched up, silt-like bones trying to hold each other and ride out this foxquake— but they are dust and they are dead. Fox licks his lips and bristles himself into menace. His tail slinks; an oil-slick in the underbrush like a name inconceivable on the tip of your tongue. His pads paw and his toes tip in between the moonlight dribble that he spots and speckles with mud in the oncoming dark. His yipping bounds across cities, lone and excitable, the shrill chasing the bark chasing the shrill, the two drowning each other somewhere along the English Channel. Fox hushes. Evening knits itself back together and Fox regurgitates the night crumbs he had devoured. The hoarse creature whorls himself mute. Sound dissolves around his teeth and gums, his screams peering along his throat like a scared child waiting to go down a park’s slide. He folds himself in half again and again until he is a collapsible piece of fox wanting to be packed away. He traces superglue along his seams and seals himself shut, suffocating in his sorry and silence.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Phil Wood: Flightless This is not about blushing blossom, but crows – funeral feathered, nesting under fascia boards, croaking their rush to gather sticks. The couple squabble like a fevered cough, or maybe not: the hushed traffic colours so much. I like these birds, they are not hoarders, but make a home. Their beauty is black, their flight not us. Spring is here for them.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Sonia Jarema: Black-billed Magpie At the end of a line of conifers, a bird lies still as death, holding in its beak a brown leaf – a needle, scales softly overlapping its length: death catching death. A shell-like rim of white rings the bird’s clear eye, and black then white feathers give way to startling blue then green. Birds are the masters of hiding illnesses till it’s too late to be saved and feathers hold true over any breech.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Stella Wulff: Spring Fever A clear head of sky relieved of the throb of planes, throws off its damp, grey cover, yawns in this new liberation of airways. Birds infectious with spring fever puff their chests in full-throated song; the soggy lawn wheezes under a cough of warm breeze. A gang of daffodils, oblivious to the whirring scythe heading their way, paints the roadsides yellow, brazenly fraternising as if immune to the vagaries of nature, as if resistant to the chill that kills the frail, the sickly, the precocious. Tulips stay home, tightlipped in isolation, strict in conformity, mustering reserves for hard times. Squirrels, who stashed enough for Winter’s siege, empty the bird feeders, their pouches stuffed to bursting. It’s every beast for himself, survival of the greediest. Bees are abuzz with this changed world order, sedulously forming a new waggle dance to instruct the hive. The queen readies herself - Spring fever stalks, dandelions mark time, temperatures rise. It takes the breath away, flutters the heart like birds in the leafless trees, flocking to the seeded air.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Pam Job: A Quicknesse, April 2020

But life is, what none can express,

A quicknesse, which my God hath kist.

Henry Vaughan

The poetic subjects are visible once again

and audible, to me, lately blinded by numbers

and graphs, and deafened by facts; but here,

in my fortunate garden, my hortus conclusus,

the dervish dance of a pair of peacock butterflies

dizzies me; and whirrings amongst plum blossom

are bees stirred by sunshine; birds, unseen, carve

the air into their own names with song; set against

acid-green spurge, a tulip has opened its throat

to turn the afternoon orange, and more. A crow

strolls across the lawn in a display of ownership.

In the pond, there’s a touching urgency about

a wriggle of tadpoles, as if there’s no time to lose.

And yesterday I talked, over a distance, to you,

old friend, both of us knowing, without saying,

if you step outside your door, you may die. Stark,

simple and so close, half your lung already forgets

about breath. You speak of planting seeds in boxes

on your windowsill, and together we imagine such

burgeoning in summer, such a harvest to come

before a quickness of wings brings a winter sky.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

John Freeman: Comfort for My Aunt Can you make me better, my aunt says, smiling at the doctor who is standing at the foot of her bed, knowing the answer, and manifesting no agitation, almost teasing him because he cannot, and we all know it, that’s why my brother and I have come all this way to see her. It’s a mark of her character, her style, to say with such composure, such good grace and so many layers of implication, lightly, can you make me better, with a smile, hinting gaily, though she’s ninety something, at a girlish mockery, and the doctor, without showing if he does or doesn’t appreciate the richness of the moment, gives without a beat his practised come-back, I can make you more comfortable, and then I hear more clearly retrospectively in my aunt’s question something in her wishing, as we all might, to believe in miracles, or never having lost the certainty that there is nothing to be done to save her, wanting at least tacitly acknowledged what nobody will say, that it’s a pity.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Teoti Jardine: In The Covid-19 Queue Being Maori, being diabetic, being the age of 75 has placed me at the head of the Covid-19 queue. Usually while waiting in a queue, I’m looking forward to an occasion, don’t mind the wait. I’ll start a conversation with another queuer, have a laugh, pass the time convivially. In this queue, there are no opportunities for conversation. The others in the queue aren’t here. This queue is a state of mind. We are all waiting, wondering, washing hands, wishing, willing. I’ll do what I can to avoid my number being called, keep 2 metres away, wear a silk hanky round my nose and mouth. I might slip down the queue. Not get the call, Step up old man, your numbers up. I’ve tasted passion in my life and if this bug is going to take me out, I’d like to go with passion. If it lets me know, and not just sneak up, I’ll welcome it with open arms. Let it take me, so, so sensuously. After all this anticipation I’ll be disappointed if it only leaves me with a little cough. Having said that, while I’ve been standing in this queue, every moment of being alive, has become a treasure.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Selese Roche: From Here From here I can see the garden April dawdling into May ‘Still frost where the sun cannot reach’ but you shake your head hearing aid on the blink again ‘Just toast and marmalade today’ the bottom of one trouser leg caught up in your sock refugees from our lives I watch us holding our own carefully coming downstairs the afternoon nap and from here I can see the garden cherry tree bathed in sunlight white blossom fanned into cups of fire everywhere lovers in the shadow of a doorway the hard light waiting beyond. Selese Roche: Lost I told my upstairs neighbour when I returned that I had lost a glove but retraced my steps and found it lodged under the wheel of a bike on the Haarlemmerplein she said she had noticed gloves do get lost at this time of year quite often she said a single glove dropped in the street and forgotten I did not mention the fact that I myself was lost I told her I had seen a man’s brown shoe on the bridge crossing over to Prinseneiland an elegant shoe lying close to the edge caked in mud from the canal laces undone

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Keith Nunes: On a park bench ‘Suicides will go up because of this’ the skinny man says The tall man says the skinny man says that every election, every time the temperature goes above the record high, every time there’s a shortage of something, he’s so complicated, he steals menus and returns them to the wrong cafe, he only talks when he’s standing up, he doesn’t work but no-one knows why he has so much money in his pockets ‘How do you know this skinny man?’ says the plump man ‘He is my husband’ the tall man says ‘We are in love, much of the time’ ‘What connects you to each other?’ asks the plump man ‘Nothing, nothing that I can identify’ says the tall man The plump man frowns, he is now a plump man frowning and the tall man asks Why are you frowning? The plump man is now smiling, a smiling plump man, he says ‘You are also complicated’ The skinny man, who is standing beside the park bench where the other two are sitting,

says ‘Our connection is that we are disconnected and that is enough, for now’ The plump man rocks back and forth on the bench, clapping his hands, laughing loudly

scaring the pigeons ‘You are a stage play’ says the plump man ‘You are Vladimir and

Estragon and I’m Godot, who has finally arrived’ The tall man stands, he is very tall, and offers his hand to the skinny man who receives it,

they bow to the plump man, and walk away The plump man calls after them, ‘Wonderful exit gentlemen’

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Hayden Hyams: Museum Alembic ‘We have made a summer camp in the forest.’ ‘We make iron and cloth in our roundhouse village.’ ‘We defend our land using beautiful bronze swords.’ ‘The insurance industry today has developed highly sophisticated theories

and technologies to put a price on a breathtaking array of products.’ There are two types of panic. Passive panic is my favourite. Hayden Hyams: Museum Alembic #2 ‘Leonardo da Vinci left over five hundred sketches and thirty five thousand words

in a manuscript devoted to flying machines, bird flight and the nature of air.

He had no influence on the development of flight.’ ‘The scheme leads victims to believe that profits are coming from product sales

or other means, and they remain unaware that other investors are the source of funds.’ ‘The sky is blue. We are always smiling.’

Back to poet list… Forward to next poet

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Neil Richards: Shuffling “sorrow and rejoicing” Found poems from Van Gogh’s letters 1876-1877 in which the words “Sorrowful yet rejoicing” are often repeated. 3/10/1876 /I walked a long way/a thunderstorm in the distance/I rested there. 31/12/1876 Brother/ we are a beautiful road/ made from silver linings/spoken by evening mass. 7-8/2/1877 /Pale faces/dark eyes/ a great many crows/speaking the same language/ the shadow of fields weeping over prayer/ 7/3/1877 /a torrent of reproaches that arrive by postcard/ Filled to overflowing/I only hope at home/a little boat floating back from the dead/ in the distance I see my Father’s heart/ 31/5/77 /I watch the rain walk on water/my hand says all of this is sea/ sea is never far from sad/ sad is in the meat of angels/I put them on juniper coals/not in the fire/a still small voice awakens 21-22/5/77 /I feel love flying faster and faster through my body/ The fervent desires of trees/as the sun sets through them/ An old woman asleep/head full of time/ the smell of rain like a warm handshake/the morning/ elderberries/tar/the North Church covered in Sundays/ 15/7/77 /The sun was shining/I met the painter/ I was lucky enough to look inside/where they build the ships/with pale tired faces/ and hair already mixed with grey/ I can see you sitting full of boats/you are raining/the sea loves you/ 27/7/77 /They drag the sun out/sorrow clings to the sun/they carried it home in a blanket/darkness filled the house/ I want to fill this sheet of paper with how still the afternoon was/ Late March 1877 /his love is more valuable in museums/it is not flowers/it is not flowers/ room is a flower/ room is a faith/ a fine collection of disciples/letter is a room/flower is a room of sermons/room is a heart/you will find in it/spare time for your collection/and letters/which struck me sorely/ I hope with all my flowers/love is more valuable than agonies/ 16/3/1877 /Sometimes I am bread/ Sometimes I am tears/ sometimes I think your heart is a sky/the sky is often busy until late at night/but it is good to be loved/ by a woman who is lit by lark song Neil Richards writes My process such as it is is an intuitive one, and one that is evolving as I engage with the texts. I read the text once from beginning to end, then work from the end back, jotting down words or phrases that strike me. Then over the course of a day or two I link them together, sometimes with a sense of the original text, sometimes not. A space after a slash indicates a longer pause. I have no plan other than to create something new from that which is already there. To quote from Simic’s “Dime-Store Alchemy”; “Cornell worked in the absence of theory. He shuffled a few inconsequential found objects until they composed an image that pleased him, with no clue as to what that image will turn out to be in the end.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Sailor and librarian, navigator and researcher, teacher and trainer, and – always – a traveler. Chris Armstrong has lived in Wales most of his life – for the last forty-five years in the country, farms and hills near Tregaron. All this – and more – has shaped the poems which reflect the joys and tragedies that life brings. He is currently working on a second collection and a novel.

William Bedford’s poetry has appeared Agenda, Encounter, The John Clare Society Journal, London Magazine, The New Statesman, Poetry Review, The Tablet, The Washington Times and many others. Red Squirrel Press published The Fen Dancing in March 2014 and The Bread Horse in October 2015. He won first prize in the 2014 London Magazine International Poetry Competition. Dempsey & Windle published Chagall’s Circus in April 2019. His latest collection, The Dancers of Colbek, was published by Two Rivers Press in January 2020

Stephen Bone’s latest pamphlet, Plainsong was published in 2018, by Indigo Dreams. A Hedgehog press ‘ Stickleback’ micro pamphlet is due in in 2020. Most recent work published or forthcoming in Agenda ( supplement), Black Bough Poetry, Finished Creatures. Morphrog, The Frogmore Papers.

Bruce Christianson is a mathematician from New Zealand. He lives in Hertfordshire, where he has been unsettled for more than a Gigasecond.

Gareth Culshaw lives in Wales. His second collection is out in 2020 called A Bard’s View. He is a current student at Manchester Met where he is studying for an MA in Poetry.

Tim Cunningham has had seven collections of poetry published since 2001; his eighth, Passports, is due out in April 2020 with Revival Press. Tim has recently returned to live in Ireland, having previously worked in education in London, Delaware and Essex. He was awarded a Patrick Kavanagh fellowship in 2012.

Marie Dullaghan was born in Dublin. and is a retired education worker, fine arts photographer, musician, actor, writer and poet. She is a long-term member of both the Poeticians and Punch collectives in Dubai and performed regularly at events including the Emirates Airlines Festival of Literature. She hass work published in The Shop, The High Window and elsewhere

David Flynn was born in the textile mill company town of Bemis, TN. His jobs have included newspaper reporter, magazine editor and university teacher. He has five degrees and is both a Fulbright Senior Scholar and a Fulbright Senior Specialist with a recent grant in Indonesia. His literary publications total more than 230. Among the eight writing residencies he has been awarded are five at the Wurlitzer Foundation in Taos, NM, and stays in Ireland and Israel. He spent a year in Japan as a member of the Japan Exchange and Teaching program. He currently lives in Nashville, TN.

James Fountain was born in Hartlepool in 1979. My work been published by magazines such as London Grip, Dreamcatcher, The Journal and The Blue Nib – the latter I also review new poetry collections for. My second pamphlet The Last Stop was published by original plus press and chosen as runner up in Ilkley Literature Festival’s Best New Chapbook contest, judged by Imitiaz Dharker. I currently teach in Saudi Arabia (where I’m now locked in!)

John Freeman grew up in south London and lived in Yorkshire before settling in Wales,where he taught for many years at Cardiff University. His poems have appeared in many anthologies and magazines. His tenth collection, What Possessed Me (Worple Press), won the poetry section of the Wales Book of the Year Awards in 2017. Other recent books include Strata Smith and the Anthropocene (Knives Forks and Spoons Press), A Suite for Summer (Worple), and White Wings: New and Selected Prose Poems (Contraband Books). His poem ‘Exhibition’ won the Bridport poetry prize in 2018.

Carl Griffin is from Swansea, South Wales, and has had one book of poetry, Throat of Hawthorn, published by Indigo Dreams

Hannah Hodgson is a 22 year old poet living with a life limiting illness. She writes about Disability, Hospice use and Family Life. She has had poems published in Under the Radar, Acumen and Ink Sweat and Tears amongst others.

Margaret Hollingsworth divides her time between the U.K and Canada. She has taught creative writing in many Canadian universities including a 10 year stint as a professor of writing at the University of Victoria. She is best known as an award winning playwright but has concentrated on poetry in recent years. She has published in numerous literary magazines and looks forward to the publication of her first collection at the end of this year

Hayden Hyams is a poet from Aotearoa New Zealand. He is fascinated by the sublimation of meaning through the reframing of phrases and paragraphs found in ordinary life, often sampling from Facebook, Google searches and Museum tombstones. His poetry can be found in Poetry New Zealand, Takahe and The Friday Poem. He is working on a collection of poetry named Fragments.

Teoti Jardine of Maori, Irish, and Scottish bones. He lives with his dog Amie in their Covid-19 Lockdown Bubble in Aparima/ Riverton, on beautiful southern coast of New Zealand. His poetry has often found a home with London Grip

Sonia Jarema was born in Luton to Ukrainian parents. Her poems have been published in Envoi, South, The North, Stand and Interpreter’s House as well as being commended or shortlisted in various competitions. Her novel was longlisted for Penguin Random House WriteNow program 2016. Her debut pamphlet Inside the Blue House is available from https://palewellpress.co.uk/

Based in Wivenhoe, Essex, Pam Job’s work appears in magazines including Acumen, The Interpreter’s House, Magma, and in various anthologies. Among her recent awards is Second Prize in the Magma Poetry Competition 2018, First Prize in the Cornwall Contemporary Poetry Competition 2018, and, in 2019, Commendations in Second Light Competition, the Crabbe Memorial Competition and a Highly Commended in Charroux Literary Festival Competition. This year, she was awarded a Fourth Prize in the Kent and Sussex Competition. Her poem, The Parcel, was included in a new oratorio, The Affirming Flame, premiered at Snape Maltings in 2019.

Tess Jolly has published two pamphlets: Touchpapers’ with Eyewear and Thus the Blue Hour Comes’with Indigo Dreams. Her debut collection Breakfast at the Origami Café is forthcoming from Blue Diode Press.

Richie McCaffery lives in Alnwick, Northumberland. He’s the author of two poetry pamphlets, including Spinning Plates from HappenStance Press as well as two book-length collections from Nine Arches Press, Cairn and Passport. In 2020 he’s to publish a pamphlet with Mariscat Press as well as an edited collection of academic essays on the Scottish poet Sydney Goodsir Smith (Brill / Rodopi).

Ray Miller is a Socialist, Aston Villa supporter and faithful husband. Life’s been a disappointment.

Tim Miller’s most recent books are Bone Antler Stone (High Window Press) and To the House of the Sun (S4N Books). He is online at www.wordandsilence.com.

Kate Noakes’ most recent collection is The Filthy Quiet (Parthian, 2019). She lives in London where she acts as a trustee for writer development organisation, Spread the Word. Her reviews of poetry can be read in Poetry London, Poetry Wales, The North and London Grip

Keith Nunes (Aotearoa/New Zealand) was nominated for Best Small Fictions 2019, the Pushcart Prize and has won the Flash Frontier Short Fiction Award. He’s had poetry, haiku, short fiction and visuals published around the globe

Ava Patel has recently graduated from the University of Warwick with a First in an MA in Writing. She has continued to write poetry since her Degree and had some small successes being published in a webzine (the Runcible Spoon) and a magazine (South Bank Poetry).

Stuart Pickford lives in Harrogate and teaches in a local comprehensive school. He is married with three children. His second collection, Swimming with Jellyfish was published by smith|doorstop.

Neil Richards currently lives in Worcester and has been writing for around five years. He has been published in Ink Sweat and Tears, Strix, Riggwelter, Domestic Cherry and elsewhere. He has had a pamphlet published with Frosted Fire Firsts.

Belinda Rimmer’s poems are widely published. In 2017, she won the Poetry in Motion Competition to turn her poem into an award winning film. In 2018, she came second in the Ambit Poetry Competition. She was runner-up in the 2019 Stanza Poetry Competition. She was also joint winner of the Indigo-First Pamphlet Competition, 2018, with Touching Sharks in Monaco

Selese Roche is an Irish, freelance editor living between Kildare and Amsterdam who has been writing poetry for a few years.

John Short lives in Liverpool and is a member of Liver Bards. Recently published in Envoi, Marble Poetry, The Cannon’s Mouth, Orbis and South Bank poetry he is a Pushcart Prize nominee. His full collection Those Ghosts (Beaten Track) and pamphlet Unknown Territory (Black Light Engine Room) will be out hopefully later in the year.

Jane Simpson is a poet, historian and editor based in Christchurch, New Zealand. She has taught social history and religious studies in universities in Australia and New Zealand. Her second collection, Tuning Wordsworth’s Piano (2019), and A world without maps (2016) were published by Interactive Press (Brisbane). She has recently completed a manuscript with the working title, ‘Dress rehearsal for old age’.

Barry Smith is co-ordinator of the Festival of Chichester and director of the South Downs Poetry Festival. Published in journals such as Agenda, Acumen, South and Frogmore Papers, he was runner-up in BBC Proms Poetry competition. Barry is editor of Poetry & All That Jazz. He is also a performance poet with jazz and roots musicians.

Phil Wood was born in Wales. He has worked in Education, Shipping, and a biscuit factory. His writing can be found in various publications, including: Ink Sweat and Tears, The Runcible Spoon, Allegro, Califragile.

Stella Wulff has a deep love of the natural world and a fascination for politics and the human condition—themes that she explores in her poetry. She has poems in several anthologies, including the award winning #MeToo. Placed third in the Sentinel Literary Competition, nominated for Best New Poet Anthology 2018, her work has been widely published. Journals include: The New European, The French Literary Review, Prole, Rat’s Ass Review, Ink Sweat & Tears, and many others. She is co-editor of 4Word Press who published her pamphlet, After Eden, in 2018.

Tim Youngs is the author of the pamphlet, Touching Distance (Five Leaves, 2017) and co-editor with Sarah Jackson of the anthology, In Transit: Poems of Travel (The Emma Press, 2018). His poems have appeared in several print and online magazines, including The Interpreter’s House, Litter, Magma, Poetry Salzburg Review and Stride.

01/06/2020 @ 11:13

Loved it – all Monday mornings should be spent like this!