May 21 2020

London Grip Poetry Review – Gordon Meade

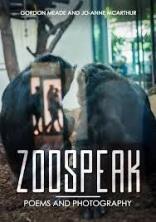

Poetry review – Zoospeak: Peter Ualrig Kennedy is extremely impressed by Gordon Meade’s latest collection in collaboration with photographer Jo-Anne McArthur

Zoospeak Gordon Meade Enthusiastic Press Ltd. ISBN 978-1-9161130-4-6 111pp £6.99

This is a very special book: Zoospeak – a collaboration between Scots poet Gordon Meade and the Canadian photographer and animal activist, Jo-Anne McArthur. This recent collection is unique, innovative, moving … Unique in its central theme, a sweeping worldwide view of captive animals; innovative in its poetic structure, and in the co-operation between photographer and poet; moving in the way that the poet gives empathetic voice to the emotions of these captive but sentient beasts and birds and fish.

Gordon Meade’s fifty or so poems are presented in four sections. There is one header poem, at the start, ‘A Deer in the City, USA, 2005’ – and there is one sad tail-ender, ‘Washed-up Calf Corpse, Israel, 2018’. Each poem is evocatively illustrated with McArthur’s photographs. Indeed, the genesis of this collection lay in McArthur’s travelling to zoos far and wide, and in her remarkable photographs which inspired Meade’s lyrical responses. The photographer’s foreword to the book is itself a wonderful accolade for the poetry itself.

In 2017 Meade acquired a copy of McArthur’s book, Captive, and found himself “totally unprepared for the impact that Jo-Anne’s images” would have on him. Furthermore, he writes “Nor was I prepared for the poetic form that presented itself to me as I began to try and write a response to them.” As it turned out, his style in the poems proved to “mirror the symptoms of zoochosis in the various animals – pacing, walking in tight circles, rocking, swaying and, at times, self-harming.”

These poems are intensely moving, each using the first person, and each one is meticulously constructed. Right from reading the first poem, what is immediately striking is the structure. Meade says “As for the format of the Zoospeak poems, it just seemed to come to me. I am not sure if I will use it again, but it worked for these particular poems.” Each opening stanza is of three lines only. Each succeeding stanza is a repetition of the one before, with the addition of one line, and this repetition leads to a final stanza of nine lines. The repetition engages the eye and the mind, and builds a ziggurat of words, providing striking layers of meaning.

This methodical repetition, bolstered by the new revelations of each added line, makes these poems particularly powerful. It is not enough to skip to the last stanza of the poem; it is important, indeed imperative, that one should read each stanza in turn as the individual animal’s story unfolds. The stories are acutely observed tales of the sad endurance, in enforced captivity, of each caged animal. They are humbling. The animals speak to us through Gordon Meade’s exquisite words, and their stories grip you by the throat.

Here is ‘Baltic Grey Seal, Lithuania, 2016’ – as the animal is introduced to its new enclosure:

. . . . . . . . . . . The water too is blue. The rubber ring is red, but my skin is grey just like the Baltic Sea in which I was born and to which I shall never be able to return.

In quoting from these poems I lose the insistent building of narrative from one stanza to the next – the only remedy is for you to get hold of this marvellous collection and read all the poems for yourself. Here is the final stanza of ‘Brown Bear, Croatia, 2016’. The creature imprisoned behind bars brings us face to face with the contempt that caged animals might feel for us their captors:

I used to be just fur, claws, snout, and skin. But now, thanks to you and your kind, I am also, Perspex, metal, concrete, and stone. I have no way of knowing where I end and the rest of the world begins; where I begin and the rest of the world ceases to exist. I am no more what you would call a ‘proper’ bear, in the same way as you are no longer what I would call a human being.

There is defiance, sad resignation, and mordant humour in these poems. I am struck by the empathy and depth of feeling that Meade demonstrates in each vignette. The poems are individually, and as a whole, heartbreaking. The last poem in the collection, after all the images of caged animals and birds and fish, is of a dead animal, a washed-up calf corpse, who delivers a bitter coda:

Now, I am nothing more than a visual image

of what, because of you, I have become.

I shall finish this review with an admonition to you to purchase this admirable collection, and finally close with these words of Anthony Douglas Williams, Canadian writer and animal rights activist, quoted by Gordon Meade at the beginning of Part Four of the book: “One day we will know that all animals have a soul. Hopefully, this knowledge does not come when it is too late.”

21/05/2020 @ 13:46

If I may, I’d like to humbly submit the link from where this amazing collection can be purchased:

https://www.etsy.com/uk/shop/EnthusiasticPress

Thanks so much,

Dave Rogers

Enthusiastic Press